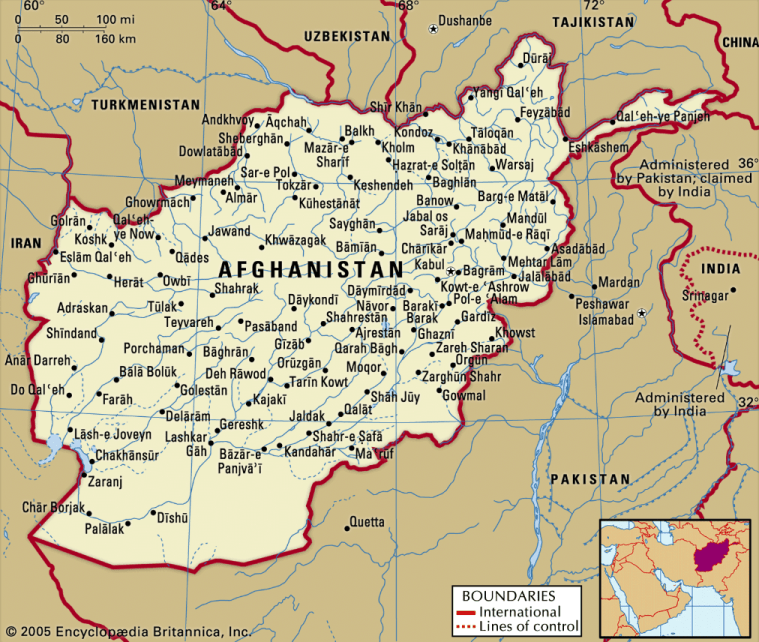

In Fall 2025, I spent three weeks in Afghanistan travelling through Kabul, Bamiyan, Ghazni, Kandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif. The following is a recounting of the interesting parts of my travels and readings on the country.

By far the best source I’ve found for understanding Afghanistan and particularly the Taliban is Taliban: The Power of Militant Islam in Afghanistan and Beyond by Ahmed Rashid, a Pakistani journalist who was in and around Afghanistan for much of the 1990s. I read the third edition published in 2022 as an update of the book originally published in 2000. The foreword in my version claimed the book was currently banned in Afghanistan, so I prayed to Allah that the Taliban wouldn’t look through my Audible app.

To understand the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan and the failed attempt to build a Western-backed government, I read The American War in Afghanistan: A History by Carter Malkasian, who is now a historian but during the war worked in numerous advisory roles for American government agencies operating in Afghanistan. It’s an extremely impressive work, and though I think it pulls a few punches on the Afghans, the book is both highly insightful and shockingly readable for something so long and dense.

I read The Great Gamble: The Soviet War in Afghanistan by Gregory Feifer, a journalist and Russian expert. It helped fill in a bit of the color of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, but it was too narrative-heavy for me and didn’t have enough discussion of broader trends.

I also read The Places in Between by former British MP Rory Stewart. It’s a memoir about a few months he spent walking across central Afghanistan from Herat to Kabul in 2001, shortly after the Western invasion and overthrow of the Taliban; it’s also a good reminder that no matter how much I travel, I’ll never be a Real Traveller.

Finally, I found a bunch of articles and podcasts from Graeme Wood to be extremely insightful (ex. “This Is Not the Taliban 2.0” or his appearance on The Remnant). IMO, Wood is the best journalist working today.

Other minor sources are linked within.