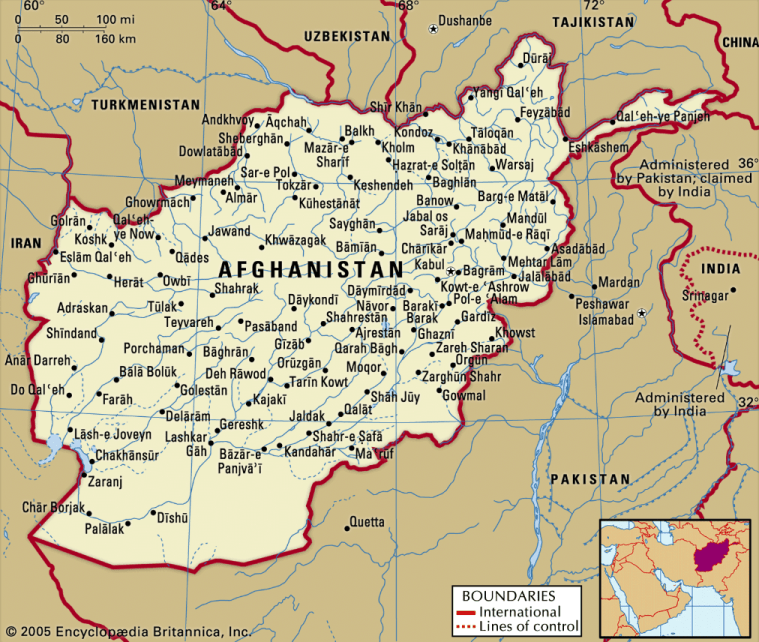

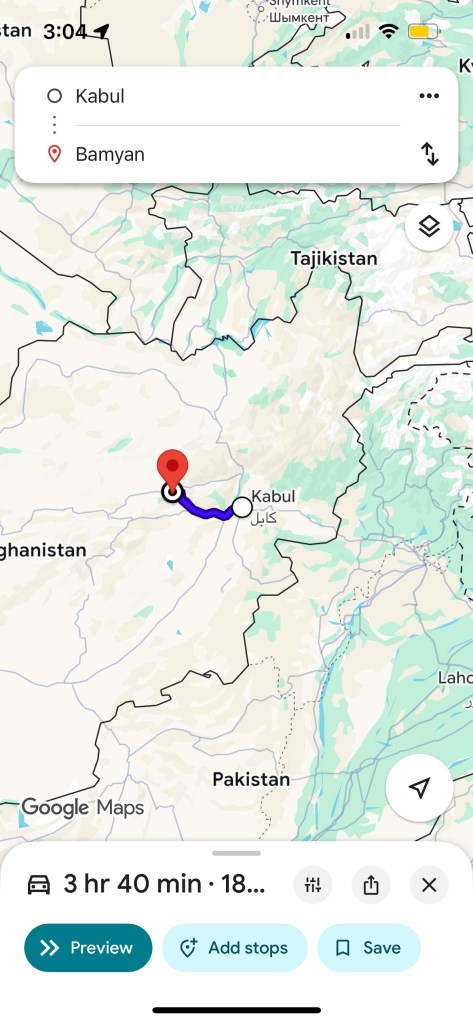

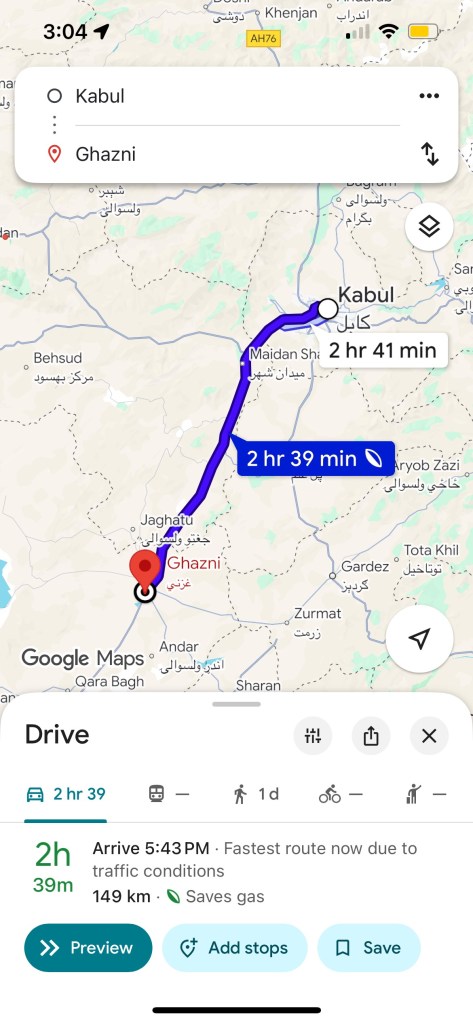

In Fall 2025, I spent three weeks in Afghanistan travelling through Kabul, Bamiyan, Ghazni, Kandahar, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif. The following is a recounting of the interesting parts of my travels and readings on the country.

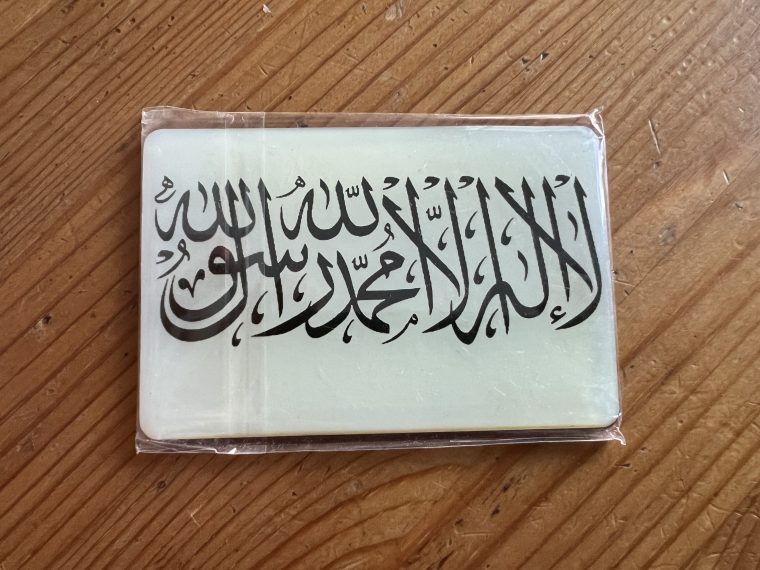

By far the best source I’ve found for understanding Afghanistan and particularly the Taliban is Taliban: The Power of Militant Islam in Afghanistan and Beyond by Ahmed Rashid, a Pakistani journalist who was in and around Afghanistan for much of the 1990s. I read the third edition published in 2022 as an update of the book originally published in 2000. The foreword in my version claimed the book was currently banned in Afghanistan, so I prayed to Allah that the Taliban wouldn’t look through my Audible app.

To understand the post-9/11 invasion of Afghanistan and the failed attempt to build a Western-backed government, I read The American War in Afghanistan: A History by Carter Malkasian, who is now a historian but during the war worked in numerous advisory roles for American government agencies operating in Afghanistan. It’s an extremely impressive work, and though I think it pulls a few punches on the Afghans, the book is both highly insightful and shockingly readable for something so long and dense.

I read The Great Gamble: The Soviet War in Afghanistan by Gregory Feifer, a journalist and Russian expert. It helped fill in a bit of the color of the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, but it was too narrative-heavy for me and didn’t have enough discussion of broader trends.

I also read The Places in Between by former British MP Rory Stewart. It’s a memoir about a few months he spent walking across central Afghanistan from Herat to Kabul in 2001, shortly after the Western invasion and overthrow of the Taliban; it’s also a good reminder that no matter how much I travel, I’ll never be a Real Traveller.

Finally, I found a bunch of articles and podcasts from Graeme Wood to be extremely insightful (ex. “This Is Not the Taliban 2.0” or his appearance on The Remnant). IMO, Wood is the best journalist working today.

Other minor sources are linked within.

Overview:

Population (2024) – 42.65 million

Population Growth Rate (2024) – 2.8%

Size – 252,072 square miles (a little bigger than France, a little smaller than Texas)

GDP (nominal, 2023) – $17.2 billion (less than Moldova)

GDP growth rate (2023) – 2.3%

GDP per capita nominal (2023) – $414 (by some estimates, the second-lowest in the world after South Sudan)

GDP per capita PPP (2024) – $2,201 (bottom #10-15 globally)

Inflation rate (2020-2024)- Wild swings from positive double digits to negative double digits

Biggest export – Coal

Median age (2025) – 17.3 years

Life expectancy (2023) – 66 years

Murder rate (2022) – 4 per 100,000 (I would not put a lot of stock in this figure)

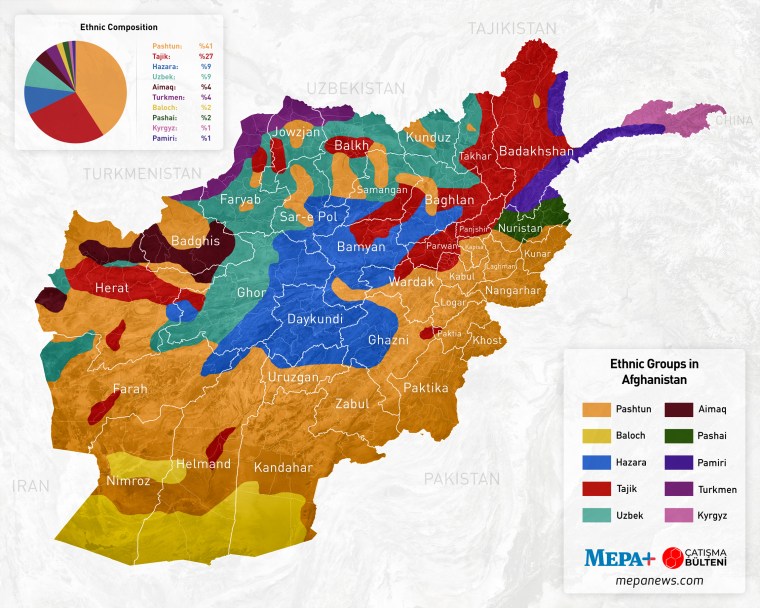

Ethnicity (2012) – ~40% Pashtun, ~25% Tajik, ~10-15% Hazara, ~10% Uzbek, and a bunch of other small groups (all very rough estimates)

Religion (2020) – 1000000% Islam (about 90% Sunni, 10% Shia)

Corruption Perceptions Index – Rank #165/180

Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom – “Not Graded”

Why and How Does One Go To Afghanistan?

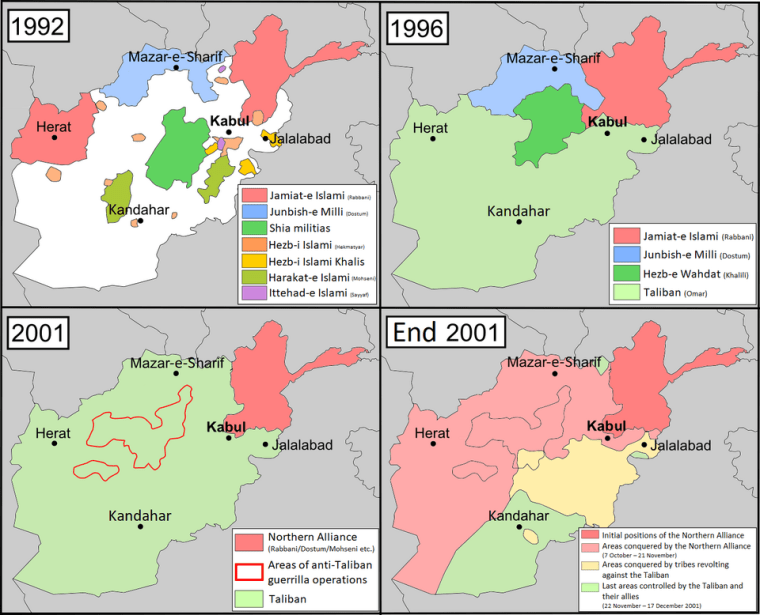

In 1973, the multi-century old Afghan monarchy was overthrown by a cousin of the King named Mohammad Daoud, who named himself president but ruled as a mostly secular quasi-dictator. In 1978, Daoud was overthrown by a communist government. In 1979, the communist leader was killed in a coup by another communist. Later in that year, that communist leader was killed by a commando squad deployed by the Soviet Union. Then, from 1979 to 1988, Soviet troops were deployed to Afghanistan to fight alongside the communist government troops against the Mujahideen, a highly diverse and loosely aligned coalition of Islamic Afghan rebels assisted by foreign Islamist fighters (including Osama Bin Laden). In 1988, the Soviet military left Afghanistan. In 1992, the Mujahideen won and the communist Afghan government fell (total estimated death toll of the entire war = ~1-3 million). Within literally weeks, the Mujahideen groups splintered into mostly ethnic-based factions commanded by warlords who fought each other for control of Afghanistan. The country descended into anarchy as day-to-day governance and law was run by the whim of local commanders who could do whatever they wanted to whoever they wanted, and often did so. In 1994, the Taliban arose in southern Afghanistan and promised an end to the chaos. In 1996, the Taliban captured Kabul and took control over about half the country.

By 1998, the Taliban controlled about 85% of Afghanistan and they proceeded to establish one of the worst regimes on earth. Just about all forms of recreation – cinema, music, board games, kites, etc. – were outlawed. Women were banned from nearly all work, forced to cover their heads and faces, and reduced to near-slave status. Men were legally obligated to have beards as long as their fists. Men and women could be subjected to punishments like impromptu beatings, whippings, cutting off hands, or cutting off heads at the whims of religious police given nearly complete power by the Taliban.

Then, in 2001, within a few months of 9/11, the Taliban was overthrown by US-led Western military forces coordinating with the anti-Taliban coalition (the Northern Alliance), and a Western-backed state known as the Republic of Afghanistan was established. In August 2021, the Republic of Afghanistan fell and the Taliban’s Emirate of Afghanistan re-rose in its place.

Soon after, the Taliban legalized standard tourism under its rule for the first time in its history. During the 1995-2001 Taliban era, tourism was restricted in part because the Taliban never fully won the civil war so there was always low-level fighting on the periphery of its territory, in part because the Taliban came from deep rural Afghanistan/Pakistan and was weary of foreigners in general, and in part because the Taliban was doing stuff like publicly stoning adulterers to death in soccer stadiums and didn’t want foreigners to see.

But the new Taliban regime that took power in 2021 was a bit different. Allegedly. It was the Taliban 2.0. It wasn’t exactly progressive, but it claimed to be a little more diplomatically open now that the Afghan people had experienced 20 years of quasi-Western rule and everyone has TikTok. Plus, without Western boots on the ground + international aid, the already dire Afghan economy collapsed to sub-sub-Saharan depths, so the Taliban needed money badly.

From the Taliban’s own numbers, they got 2,300 tourists in 2022, 7,000 in 2023, and almost 9,000 in 2024. The early tourists to take the Taliban up on their offer were mostly thrill-seekers, particularly YouTubers, who chose to believe the Taliban’s claims about Afghanistan now being safer and more secure for tourists than any time in its modern history. In terms of crime and warfare, this seems to be true as there are no reported incidences of tourists in Afghanistan being killed or harmed by either, with the exception of when three Spanish tourists were gunned down by ISIS in a Bamiyan market in 2024.

But the bigger concern for tourists, though the Taliban would never admit it, wasn’t the degree of safety provided by the Taliban, but rather safety from the Taliban, which has not been great. By my count, there have been at least seven instances of the Taliban detaining single tourists or groups of tourists from the United States and Britain on dubious or likely fabricated grounds, including an American Delta Airline mechanic in 2022 and an elderly British couple in February 2025.

Fortunately, again just to my knowledge, every arbitrarily detained tourist was released eventually, sometimes within days, usually within months, occasionally in over a year. As of late 2025, there are no American or European embassies in Afghanistan, besides Russia’s, so if any Westerners are arrested in Afghanistan, they likely have to go through a long and tedious diplomatic process just to begin grinding the gears of international diplomacy to get released.

Even still, diplomatic relations between Afghanistan and the rest of the world have been steadily warming on net since the Taliban came to power in 2021. Despite Western concerns that the return of the Taliban would usher in a new age of unprecedented awfulness in Afghanistan, thus far, the Taliban have been mostly, kind of, imperfectly on their best behavior. There was no post-war bloodbath of previous regime loyalists, adulterers aren’t being publicly stoned to death in stadiums, and the Taliban isn’t hosting terrorist groups that are attacking Western countries (only Pakistan). In fact, the Taliban is fighting a terrorist group that is attacking Western countries.

And so the Emirate of Afghanistan has been slowly inching itself closer to being on minimally respectable diplomatic terms with the rest of the world. Officially, the US has had a ceasefire with the Taliban since American soldiers pulled out of Afghanistan in 2021, and though the US still officially lists the Taliban as a terrorist organization, it’s on a lower tier than the likes of Al Qaeda or ISIS. Diplomatic connections between the US and the Taliban have gotten considerably smoother since the famously diplomatically adept Qataris became the official diplomatic representatives of America, and have secured numerous prisoner releases, especially in the last two years.

Non-Western countries, particularly Russia and China, have made more aggressive inroads in Afghanistan to rebuild some infrastructure and develop mineral extraction potential. In July 2025, Russia became the first country in the world to recognize the Emirate of Afghanistan as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, but other states give the Taliban some form of diplomatic recognition. For instance, India has become quite cozy with the Taliban in late 2025 as a diplomatic maneuver against eternal rival Pakistan.

Which is all to say that by mid-2025, I felt like Afghanistan might be safe enough for me to consider visiting. A rough analogy:

Riding in taxis in places like Afghanistan or any extremely poor country is a harrowing affair, particularly on highways. Drivers love to go into oncoming traffic lanes to get around cars or trucks going slightly slower than them This behavior is literally life-risking, and I’m fairly certain that the closest I have come to dying while travelling has been during these maneuvers, particularly a legitimately terrifying instance in Kyrgyzstan where the driver was texting while pulling around a truck, and if it wasn’t for the oncoming car screeching to a halt, we would have either smashed head on into him or veered right into the side of the truck or swung left off a beautiful Kyrgyz mountain cliff.

The way I get myself through such car trips is to repeatedly remind myself that the driver and I have the same incentives. The driver must value his own life, right? Perhaps not as much as I value my own life, but still. The driver does not want to crash into another car head-on and die, so when he does this maneuver, he is trying his very best not to die, and therefore is doing his very best to keep me alive. Hopefully.

When I started researching my trip to Afghanistan, I was inundated with a strong salvo of Afghan propaganda… the Taliban want tourists. This sentiment is echoed in every blog, YouTube video, relevant Facebook page, and official Taliban press releases. The Taliban want tourists.

This was exactly what I wanted to hear. My incentives are aligned with the Taliban’s. The Taliban want tourists, so if I were a tourist, they would treat me (an American) well, because if they didn’t, it would be an international news story (because I’m American), and then the Taliban would get fewer tourists, and they would get less money. I had to take the Taliban at their word that they don’t want to run a weird pariah state again. They may have won the war against the US and Western forces eventually, but it cost 20 years, tens of thousands of lives, and pretty much all that remained of Afghanistan’s wealth. So this time, the Taliban wants to build a very marginally more cosmopolitan society, and part of that process involves attracting international tourists with their sweet, sweet dollars, Euros, rubles, and RMB. The Taliban wants tourists, so if I am a tourist, they are unlikely to arrest and/or kill me.

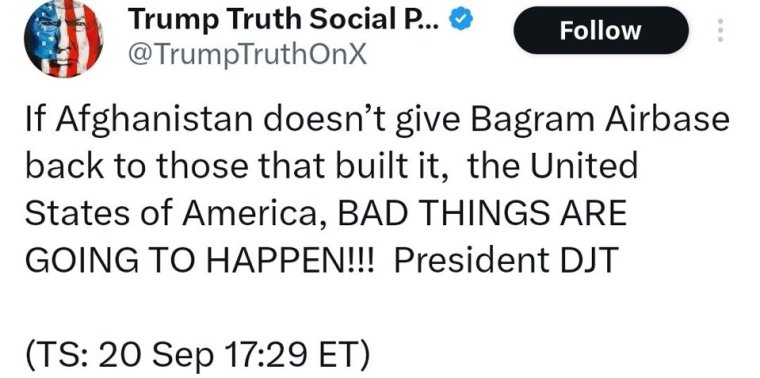

Of course, this logic only goes so far. The insane drivers executing the passing maneuvers may have my and their best interests at heart, but they can still have bad judgement. In my opinion, even the best of third world drivers can’t pull off that maneuver 10,000 times in a row, so every taxi ride is something of a lottery ticket for death. Likewise, the newly hospitable Taliban could still arrest a tourist if the relatively placid diplomatic status quo were to be upended for whatever reason. Like, if, theoretically, a very stable genius with a nuclear arsenal suddenly started threatening the Taliban over an abandoned air base.

I almost always travel alone. I prefer being able to go where I want when I want without having to worry about other travellers. Plus, in my experience, I meet far more locals when I’m alone compared to when I’m travelling with companions. However, I was a little nervous about travelling through Afghanistan alone given the potential pitfalls. So I decided to hire a guide for my first few days in Kabul to show me the ropes, and then travel around the country by myself for the rest of the three-week trip.

After some Googling, I contacted two tour companies and told them my plan. Both said it was impossible. They claimed that tourists were legally required to have guides while travelling around Afghanistan. I contacted a third guide, this one independent, and he told me I should have a guide while travelling around Afghanistan, but it was possible to do it solo. We haggled a bit and settled on a too high price to secure his loyalty, though I wouldn’t have to pay until I saw him in person in Kabul because he didn’t know what cryptocurrency was or any other way to send him money digitally.

Speaking of money, the guide told me that there were no functioning ATMs in Afghanistan, and that I could legally bring up to $5,000 in cash into Afghanistan, but could only take $500 out of the country, so I would have to pretty closely predict how much money I was going to spend in Afghanistan over three weeks, and take that amount with me. If I brought too much, I’d have to spend it in the country; if I brought too little, I guess I’d be screwed. I’ll have a lot to say about my guide later, and overall he was awesome, but like many other things he told me and many things I read on Afghan travel forums and Facebook groups, his guidance was only about 50% accurate.

That accuracy level extended to his advice on getting an Afghan tourist visa. As of writing this, the Emirate of Afghanistan has 22 diplomatic missions abroad. From researching, the ability of a tourist to get a visa at any one of these locations is extremely variable and arbitrary. Some give it out easily, some not all, some are cheap, and some cost an arm and a leg. Most people recommend going to Dubai or Peshawar in Pakistan, but I decided to roll the dice and take my chances in Doha, Qatar.

Why? For one, the Doha embassy was the Taliban’s first international diplomatic consulate, and it was where much of the negotiations to end the American war took place, so it had some historical value. And second, I had never been to Qatar, and my self-esteem is based on my country count, so I figured I’d knock out a little petrol state on my way to Afghanistan. I consulted my guide, and he said I would have no trouble getting the visa in Doha.

About two weeks before my flight out of the US, Israel launched an airstrike on Doha to try to kill a bunch of Hamas leaders. The bombing site was in a suburb of the city and coincidentally not far from the Afghan Embassy. Here I was worried about my safety going to Afghanistan and now I had to worry about getting airstriked by the IDF while just trying to get my tourist visa.

Two weeks later, I was standing in the security line at the airport, scrolling through my phone, when I saw that President Donald Trump had posted this on Truth Social:

Great. I spent the next few days in Qatar trying to figure out how much of my time, physical safety, and life I was willing to risk based on Trump’s behavior over the following month. An errant Truth Social post could literally lead to my arrest as one of the probably dozen Americans idiotic enough to go to Afghanistan at this particular time. I briefly considered abandoning the Afghanistan expedition entirely to go to Oman or maybe Pakistan, but decided to just go ahead with the planned trip anyway. Maybe I do value my life as little as those third world taxi drivers.

My Uber ride from my hotel to the Afghan Embassy in Doha took me to the Leqtaifiya neighborhood, and I noticed a street blocked off by Qatari police, which I assume is the bombed area where the Hamas leaders may or may not have been living (they all reportedly survived the airstrike). The nearby Afghan Embassy is a modest building surrounded by beige walls. To avoid an immediate diplomatic faux pas, I refrained from taking pictures of the embassy, and then after being let through the front gate checkpoint, I immediately committed a diplomatic faux pas by neglecting to take off my shoes when I entered the main office waiting room area. To be fair, I was the first visitor of the day, and so there were no shoes on the ground at the entrance, so I didn’t know I was even supposed to take off my shoes until my second trip to the embassy. Oops.

Inside, I had my first encounter with the Taliban. The guy sitting behind the glass wore traditional Afghan clothes and a turban. He looked at me with moderate surprise for a few seconds, and then turned around and called back to somewhere. Then another Taliban guy wearing traditional clothes and a turban came to the glass and nodded for me to approach.

I guess this guy spoke the best English in the embassy, but it still wasn’t good. He greeted me and asked how he could help me. I told him I wanted a tourist visa. He asked me some questions about my background, including whether I was a YouTuber, which I accurately denied, though I withheld the bombshell that I was actually the legendary travel blogger Matt Lakeman. He asked for my passport and told me to sit down.

While the Taliban guy spent five minutes making photocopies of my passport and whatever else, I had a gander around the room. There was a sign in Arabic and English which (to very heavily paraphrase) implored the workers at the Embassy to not be too brutal in their administration of justice because doing so would create enemies; instead, they should live by the Koran and Sharia to create a just world. There was also a list of embassy services with prices; one item was a “Certificate of Celibacy,” and I wish I had the courage to ask the Taliban workers what exactly that entails. According to some Googling, for a woman to get the certificate, she needs two adult male “witnesses” and three adult male “confessors,” all of whom must swear to the woman’s celibacy, though I can’t figure out the distinction between the two categories.

The Taliban guy called me back to the window, gave me back my passport, and pointed to a piece of paper taped to a wall. It had a QR code with instructions for how to fill out an online form for the tourist visa application. I had already printed out a nearly identical form and filled it out, but apparently that was no longer in use or only used at some other Afghan embassy, or something. The Taliban guy told me to fill this new form out, submit it online, and then text the embassy on WhatsApp with a provided phone number.

So I left the embassy and did just that while spending a few days meandering around Doha. Highlights include the falcon store:

The mall that looks like tacky Venice:

And what became one of my favorite buildings on earth, the Qatar National Library:

I first went to the Afghan Embassy on a Tuesday and was supposed to fly to Afghanistan via Dubai in the very early hours of Saturday. When I filled out the online form on Tuesday and then texted the embassy, the response was “We will Contact You Once You Get Approved to Visit Afghanistan” (the capitalization is verbatim). I figured they would get back to me in a day or two.

By Thursday, I still had no response. I texted the embassy in the morning and it responded with a generic recorded text in Arabic telling me the embassy’s hours of operation. So I went back to the embassy in person, realized my shoe-wearing blunder, removed my shoes this time, went inside, and asked the same guy at the counter when I could expect to get my tourist visa.

He said they would likely get a decision to me in one month.

Great. Thanks for telling me.

I booked the first flight to Dubai and got there that night. Mercifully, the Afghan Embassy in Dubai is open on Fridays (the Islamic holy day), though it closes early, so I went to the embassy at 8:30 AM when Google said it opened. This turned out to be a lie since there were already nearly 100 people waiting in line when I arrived. Fortunately, I bypassed literally all of them to go to a tiny back office where I applied for a tourist visa. The process took one hour and cost ~$180. The last thing the Taliban guy asked me while he was giving me my passport back with my Afghanistan tourist visa was, “are you a YouTuber?”

Since I hadn’t slept the night before and I had another red-eye flight in the early morning to Kabul, I went to my guesthouse to try to sleep. If I had more time in Dubai, I would have gone to the site of the recently started Azizi Tower, which, once completed, will be 133 stories high and the second tallest building in the world behind Dubai’s Burj Khalifa. The titular “Azizi” is Mirwais Azizi, who, with a net worth somewhere in the tens of billions of dollars, is the richest Afghan in the world by a colossal margin. Of course, Azizi hasn’t lived in Afghanistan in decades (he was given citizenship in the United Arab Emirates when its economy was taking off in the 1990s), but he owns Afghanistan’s largest private bank (Azizi Bank) and he’s currently in talks with the Taliban to invest $10 billion into Afghanistan’s economy (current GDP = $17.2 billion).

I could have gotten into Afghanistan on a cushy Fly Dubai flight, but I decided to immerse myself in Afghan culture by flying on Kam Air, which is shockingly one of two of the country’s airlines. I ended up flying on Kam Air three times and I have no complaints, except that the company’s motto is “Trustable Wings,” which, as confirmed by Google, is not precisely synonymous with wings that are “trustworthy.” To be “trustable” only implies the potential to be trustworthy. Which I suppose is a good metaphor for the new Taliban. But I digress. What matters is that Kam Air successfully brought me to Kabul with a tourist visa in hand.

The Ethnicities

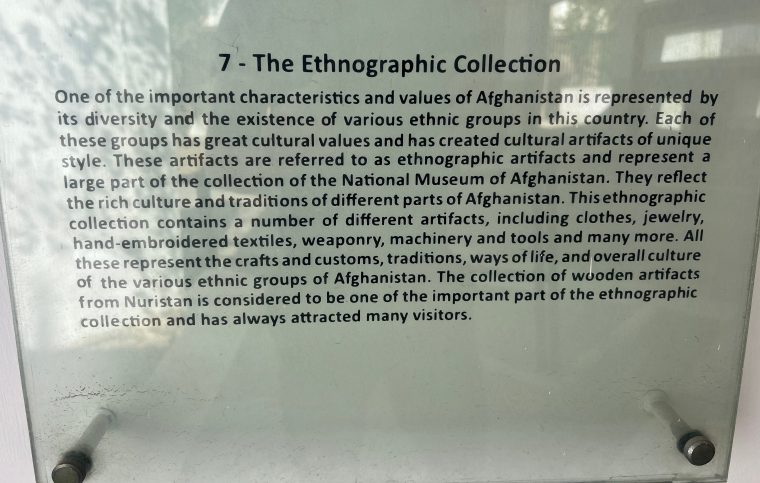

Afghanistan is ~40% Pashtun, ~25% Tajik, ~10-15% Hazara, ~10% Uzbek, and the other 10-15% consists of dozens of smaller ethnic groups. Of course, all of these numbers are extremely rough since modern Afghanistan is not known for the accuracy of its census data. To understand Afghanistan, its culture, its history, and where its future might lead, you need to know at least the basic properties of these primary ethnic groups.

Pashtuns

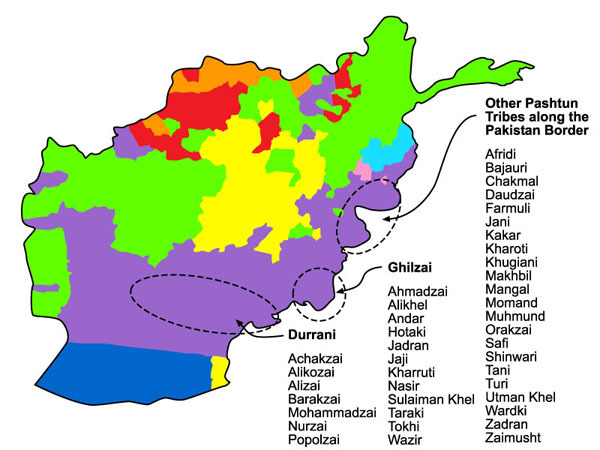

The Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan and have been the historic political leaders of the region since the rise of the Durrani Empire in the mid-18th century. They have traditionally ruled from Kabul despite being a minority in the city, while the base of the Pashtuns is in the south of Afghanistan, stretching from the Iranian border to the Pakistani border. Next door, Pashtuns make up about 15% of the population of Pakistan (which is around 40 million people, basically the same size as all of Afghanistan).

Pashtuns speak Pashto, which is an “Eastern Iranian” language, but not a form of Persian. EffectiveLanguageLearning.com puts Pashto in the second-hardest category of languages to learn for English speakers out of five groups. All I ever learned was “manana,” which means “thank you,” which is easy to remember because it sounds like “banana.”

All of the major ethnic groups in Afghanistan are highly tribal or even clannish by nature. But the Pashtuns are especially tribal and clannish by nature, with some sources calling them the world’s largest tribal population. There are a bajillion Pashtun tribes and sub-tribes across Afghanistan and Pakistan, though the two largest confederations (constituting about 2/3rds of all Pashtuns) are the Durrani (based around Helmand and Kandahar provinces) and the Ghijli (based in the southeast near Pakistan).

The Pashtun are virtually all Muslim and overwhelmingly Sunni and Hanafi. Even today, they tend to be extremely traditional, and women have very few rights legally/culturally. Men pretty much always wear long, flowing clothes, and often wear turbans. Women are usually in long, dark clothes, and burqas.

Ironically, despite being the historical leaders of Afghanistan, the Pashtuns naturally tend toward extremely localized and decentralized social structures. Though they are more urbanized today, in rural Pashtun regions, local village elders tend to hold political power, and they come to decisions by broad consensus rather than rely on single leaders. Historically, when broader political affairs needed to be decided, Pashtuns formed jirgas, or tribal councils, consisting of representatives of village elders from multiple villages, cities, or provinces.

Pashtuns are known for their Pashtunwali, an informal code of conduct for Pashtuns that includes guidance on a wide array of individual and collective topics, including settling disputes, how to treat neighbors and relatives, how to “honor” women, when to get revenge for slights, and most relevantly for me, how to be ridiculously, absurdly hospitable toward guests. It’s a little like European chivalry in some ways, but it’s a lot more like the East Asian concept of face or the North Indian/Pakistani concept of izaat (which has recently gone a bit viral).

I think it’s fair to describe Pashtun culture as chaotic. To me, it’s reminiscent of the pre-Saudi tribes of the Arabian peninsula or the feuding Nordic clans of ancient lore. Fights between Pashtun tribes and subtribes and villages and families were and are extremely common. They fight over land, resources, women, insults, everything you can imagine. One of the most important functions of Pashtunwali is to lay out the parameters by which chronic Pashtun blood feuds are started, waged, and decided. Although how successfully it does so is highly debatable.

From the above, it is both unsurprising and surprising that the Taliban is a creation of the Pashtuns, particularly the Durrani Pashtuns. I’ll go into more detail later, but the Taliban basically originated as a hybrid of the most conservative elements of Pashtun societies with radical Islamic fundamentalism. Though, interestingly, one of the most defining aspects of the Taliban, and one of the greatest sources of success in Afghanistan, was that they espoused an ideology based on sublimating tribal divisions by unifying under Islam. It’s almost like Pashtun culture taught them the follies of extreme tribalism and they learned how to beat it.

Finally, to describe my personal experience with Pashtuns… I’ll mostly get to that in the Politeness, Friendliness, and Sovereignty section. For now, I’ll just say that they are often the nicest people on planet earth but also extremely overwhelming.

Tajiks

Tajiks are the second-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, and with a population of around 10 million, there are actually more Tajiks in Afghanistan than in neighboring Tajikistan. There are also about 1.5 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan and hundreds of thousands of Tajiks in the other Stans and Russia. In Afghanistan, Tajiks are mostly based in the north where they boarder Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, but they also have enclaves in Pashtun areas, and hold the key Panjshir Valley north of Kabul.

If you take seriously the Rashid thesis that Afghanistan is a cultural product of the mixing of the sophisticated Persians and rough-riding Turkic horse nomad peoples, then the Tajiks are more Afghan than the Pashtuns since the former are essentially a genetic mix of the Western Persians and Northern Turks. They speak Tajik, also known as Dari, which is a variant of Persian.

Like the Pashtuns, the Tajiks are almost all Muslim, and overwhelmingly Sunni and Hanafi. They wear mostly similar clothes but tend to be more colorful. Afghan Tajiks are still very culturally and religiously conservative by international standards, but significantly less so than the Pashtuns.

Despite Pashtun political dominance, Tajiks have been significantly overrepresented in the Afghan military during both premodern and modern times, and have historically been the biggest competitors to both the Pashtun and the Taliban. When the Soviet-backed Afghan regime fell in 1992, a Tajik-dominated state rose in its place as the nominal government of Afghanistan based out of Kabul. Then, throughout the Civil War of the 1990s, the Tajiks had the highest quality military force and easily the best military leader (Ahmad Massoud), but they never had the manpower or political strength to gain de facto control over more than about 40% of the country. Eventually, the Taliban rose up in the south and overwhelmed the Tajik government and the rest of the Civil War factions with larger and far more fanatical armies. However, the Tajiks were never entirely defeated; they fell back to the northern Afghan mountains and successfully defended for years, until the US-led invasion overthrew the Taliban in 2001. Both during that fighting and afterward when the US formed the new Afghan government, Tajiks filled the majority of rank-and-file military roles.

In my personal experience in Afghanistan, Tajiks tend to be more pro-Western and pro-American than the Pashtuns, and they tend to be more openly anti-Taliban. They also tend to be polite without the overwhelming exuberance of Pashtuns.

Hazaras

Unlike the Pashtuns, Tajiks, and Uzbeks, almost all of the world’s Hazaras live in Afghanistan, and most of the Hazara populations elsewhere (Pakistan, Iran, Australia, etc.) are there precisely because they fled Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, the Hazaras are mostly clustered right smack in the middle of the country, in the province of Bamiyan, which lacks a major centralizing city even by Afghan standards. Other pockets of Hazaras can be found in major cities, including Kabul.

Like the Tajiks, the Hazara speak Dari, but unlike the Tajiks, the Hazara are not ethnically Persian, and you don’t need to be a geneticist to figure that out. The Hazaras phenotypically look East Asian, or more specially, Mongolian. The probably-true-but-never-actually-confirmed explanation is that the Hazaras are the descendants of Mongol settlers left behind by Genghis Khan’s conquests. In some parts of Afghanistan, the Hazaras are literally called “Mongols.”

The Hazaras have had a rough time in Afghanistan. The formation of Afghanistan as something very roughly approximating a modern nation state is usually credited to the Pashtun Abdur Rahman Khan, AKA the “Iron Emir,” who in the late 19th century waged a successful centralization campaign by fighting and subduing the region’s major tribal lords and their armies. This included slaughtering as many as 60% of the Hazaras in Afghanistan after a Hazara uprising. Afterward, the weakened Hazaras were constantly beset by the more populous Pashtun tribes to the south and Tajiks to the north. During the Civil War in the 1990s, there was even a brief period where the Hazaras sided with the Taliban against the Tajik forces, but then the Taliban kidnapped the head Hazara warlord and tortured him to death. Afterward, Hazara forces were besieged by the Taliban for over year in Bamiyan, and essentially starved out and subsequently massacred with such brutality that it has been called a Hazara genocide.

The constant historical brutality and struggle have sharpened the Hazaras into a particularly cohesive political unit. Though they have always lacked the population numbers to break out and form the mythical Hazarastan, the Hazaras tend to be more unified than the other ethnic groups, and whether due to political machinations or legitimate ideological sympathies, they tend to be more pro-Western than the rest.

A peculiar note on the modern treatment of Hazaras – one of the Taliban’s rules in the 1990s was that all men had to grow beards to about the length of a fist. That’s annoying but not too difficult for Pashtuns, Tajiks, and Uzbeks, but Hazaras are genetically closer to East Asians, and East Asians are not well known for their bushy beards. It turns out that most Hazara men literally cannot grow beards that long. Thus, during the pre-2001 Taliban era, Hazara men were constantly harassed and beaten for failing to meet the beard requirements. Many Hazara men covered their faces at all times in public, a practice still sometimes used in Afghanistan by recently shaven or trimmed men.

However, the historical and contemporary targeting of the Hazaras is not a racial matter but a religious one. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Safavid Persians tried their darndest to convert Afghanistan from Sunni Islam to Shia Islam. Only a few minuscule pockets of Pashtuns and Tajiks converted, but for whatever reason, the Hazaras went Shia en masse. The upside was gaining the Persians as an eternal ally even to this day, the downside was pissing off everyone else in Afghanistan as heretics.

I don’t want to paint too broad of a brush, but the Hazaras were my favorite people in Afghanistan. I’ll get into it more in the Politeness, Friendliness, and Sovereignty section, but I found Hazaras to be consistently the easiest Afghans to deal with. The Hazaras were also fun to talk to because they were never shy about telling me how much they really fucking hate the Taliban.

Uzbeks

The Uzbeks are the last major ethnic group in Afghanistan, with around 4 million people constituting about 10% of the population. Next door, Uzbekistan has almost 30 million Uzbeks who are currently getting quietly rich off natural gas deposits. Afghan Uzbeks are clustered in the central North of the country, though communities can be found in major cities.

Uzbeks are the most Turkic of the Afghan ethnic groups (along with the Turkmen) and they claim decent from Timur the Lame of the Timurid Empire. Their Uzbek language is Turkic and guttural compared to the smoother Persian.

If you want to go down a fun historical rabbit hole, I recommend reading about the Uzbek warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum, who was, IMO, the most interesting warlord of the Afghan Civil War. He was a gigantic “bear of a man” (Rashid’s description) who loved fighting and allegedly killed another man by screaming at him. He was an excellent commander who “acquired a reputation for brutal and extreme violence” but was also probably the single most liberal warlord in the Afghan Civil War, and governed his territory accordingly, including permitting alcohol to flood the streets (not surprisingly, he was a heavy drinker, and once said about the Taliban, “We will not submit to a government where there is no whisky and no music”). If you happen to know Metal Gear Solid lore, he is basically the Afghan Revolver Ocelot; he was the only major Afghan warlord to fight for the communists and against the Mujahideen (very well in fact), and at various points in the conflict, he sided with and betrayed the Tajik government, the major Pashtun warlord (Hekmatyar), the Taliban, the Tajik government again, the Northern Alliance, the American government, and the post-2001 Afghan government (from which he was first removed for allegedly kidnapping and torturing a political rival, but later returned to become Vice President). During the US invasion in 2001, he led a 3,000 man army entirely on horseback, which was assisted by US Army Rangers who also rode on horseback, which is the basis for the movie 12 Strong. And he’s still alive! Albeit living in Turkey in exile.

Anyway, I didn’t interact with too many Uzbeks in Afghanistan. I didn’t go to their Afghan population centers, and they aren’t too visually distinctive. For what it’s worth, my guide in Kabul described Uzbeks as “very angry people.”

Day 1

I was nervous about entering Afghanistan. From Facebook groups and forums, I heard a lot of horror stories about getting into the country. Some visitors said that the Taliban would take every single item out of your bags and inspect them individually. Some said they would take you into a private room and interrogate you about your background and intentions. Some said that they would ask you to unlock your phone and then go through your internet search history and pictures. I met two tourists in Afghanistan who admitted to deleting nude photos from their phones before arriving.

None of that happened to me in the Kabul airport or Afghanistan as a whole. Maybe it used to happen, or maybe it happens at trickier borders like up in Wakhan (as a different guide told me), or maybe it happens to particularly shady-looking tourists. But the security in Kabul just checked my passport and visa, asked a few basic questions (“why are you here?”, “where did you come from?”, etc.), and let me through.

This was good foreshadowing for my experience of travelling in Afghanistan – as a heuristic, people don’t know what they’re talking about. Guides, random locals, forums, even Taliban agents – all of them will tell you what you’re supposed to do in Afghanistan, and none of them will be entirely correct. You’ll be lucky to find someone who is 75% correct.

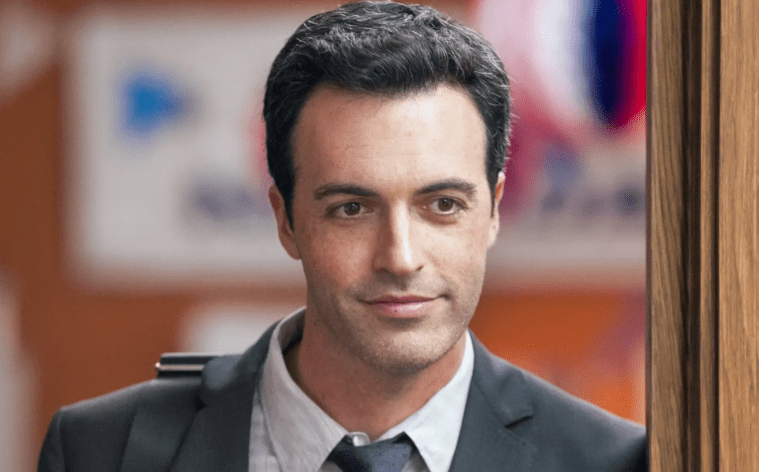

This heuristic applied to my guide, whom I met outside the Kabul airport. He was from a rural area in the north, but according to documents on his phone that I couldn’t read, he was a licensed guide in Afghanistan. His journey from his home village to Kabul had taken almost 1.5 days across two buses and a shared taxi ride. I was pleased to find that he spoke English much better than he wrote it on WhatsApp.

Up until that point, almost all of our communication had been about the trip, so we sat down in a café for some meet-and-greet chit-chat. He was soft-spoken, maybe 5’ 8, and thin. He wore the standard Afghan outfit: a vest over a loose garment that I would describe as a “dress for men,” with a scarf that could be used for warmth, covering his face from the sun, or blocking out dust/sand. He was 29 but could pass for his early 40s in the US. He had travelled all over Afghanistan with tourists but he had never left the country. He was married to a distant cousin who was uneducated and illiterate, and who he didn’t seem to like, though he did seem to like going to Kabul to get away from her. Their marriage was arranged by their parents. He had three kids whom he almost never mentioned. Including his wife, kids, parents, and various other relatives, 14 people lived in his household.

My guide didn’t graduate from high school, but I would come to think of him as quite smart. His English was among the best I encountered in the country, and that’s against a lot of competition. He learned English initially through a private service, but he said it improved greatly through conversations with tourists. He was very curious and asked just as many questions about me and US politics and culture as I asked about him and Afghanistan. He had started the tour company in 2020, had gotten some early good business, but had understandably gotten barely any customers since the Taliban took over in 2021. He supplemented his income with a small shop in his home village, which he estimates had a few hundred inhabitants.

After I finished my coffee and he finished his tea, my guide decided on using the fourth taxi we approached to get to the hotel; the first three tried to charge extortionate prices. Our driver was thrilled to have us, and not just because he still charged a higher-than-normal price. He explained, through my guide’s translation, that he had worked for “the Americans” before 2001, and after I asked for clarification, he said that he was in the Afghan National Army. I would come to learn that Afghans generally equivocate between the old government and “the Americans.” I would also have five different Kabul taxi drivers during my trip who used to work for the Western military or the old government as soldiers or drivers.

There were security guards at the airport who didn’t look too dissimilar to airport security in any other country, but during the taxi ride to my hotel, I saw my first real Taliban in Afghanistan. They were all over Kabul – at checkpoints, observing traffic, piled into pickup trucks, walking down the street, etc. They weren’t hard to spot – they always carried guns, always had turbans, always had long beards, and always wore what I would describe as robes. Outside of Kabul, they pretty much always carried AKs, but in Kabul, many carried M4s and drove around in machine-gun-mounted camo-colored Humvees. That stuff was clearly American-made, left over from the 2021 US evacuation. Some Taliban soldiers even wore American uniforms. My tax dollars at work.

While stopped in traffic, a motorcycle carrying two crammed Taliban guys drove past us while blasting music. I had read that the Taliban banned music, so I asked my guide if this was true. He explained that most music is illegal, but there are Taliban-approved songs, many of which were made by the Taliban. Apparently, all the lyrics are patriotic/Islamic propaganda about how amazing the Taliban and Afghanistan are. Nevertheless, throughout my trip, it was common for taxi drivers to play music on the radio, usually local, sometimes Western, though they always turned it off whenever Taliban were nearby, and they played it at extremely low volumes by third-world country standards.

My guide and I stayed at a decent hotel in the middle of Kabul. Since 2021, like many other relatively high-end or Western-ish establishments, it had been nationalized by the Taliban. It still functioned as a hotel, but now there was an armed Taliban guy (they’re always armed) constantly standing outside the front door or sitting in the lobby. He looked at me briefly when I arrived and then barely looked at me again for the next three days while he sat in one of these seats:

My room was decently comfy but weird. I wish I had taken a picture, but it had faux-Versailles-style wallpaper, except for the ceiling, which had different wallpaper to make it look like a blue sky on a sunny day. The bathroom had both a Western toilet and a squat toilet; I always opted for the former because I don’t always follow “when in Rome.”

This was the view from the balcony:

After a power nap, I left the hotel with my guide to explore Kabul a bit. We were ideally situated in the city center, which, like the center of every other Afghan city, was a giant bazaar extending in all directions. The urban chaos levels of these bazaars didn’t quite reach India or Nigeria levels, but it was close.

One oddly un-chaotic thing I quickly noticed was the noise level. I’ve written before (ex. about Guyana) that the idea of wanting a quiet public square is a uniquely Western concept, or possibly a uniquely Anglo/Germanic/Scandinavian/East Asian concept. Everywhere else in the world is fine with constant blasting noises, or even prefers them. In that frame of mind, I found Afghanistan to be surprisingly quiet, even at the heart of its urban areas. Obviously there was still plenty of noise from cars and people talking, but:

- The main languages (Pashto and Dari) seem naturally pretty quiet.

- Shouting is rare and seems to be frowned upon.

- Unlike most markets in poor countries, there are no speakers blasting sales and prices. I suspect this is due to a Taliban prohibition since the only time in Afghanistan I heard a speaker was from a Taliban van driving down a street in Herat blasting Allah-knows-what propaganda.

- Also extremely unlike most markets in poor countries, there was no BLASTING music, which was another gift of the Taliban.

What does reach the chaos levels of India and Nigeria are Afghan roads. There are technically stop signs and streetlights and crosswalks, but they are vague suggestions at the best of times. People drive like they walk, with both an incredible level of vehicular proprioception (which I lack) and a far higher tolerance for minor collisions.

In nearly all regards, all three countries have very low-trust societies, but when it comes to crossing the street, Afghanistan (and to a lesser degree India and Nigeria) are extremely high-trust societies. The way you walk across a busy city center street in Afghanistan is you just go and give your complete and utter trust to every car around you that it won’t hit you. You can’t wait for openings in traffic; they don’t exist. The best strategy the pedestrian can pursue is to strike a reasonably slow, but more importantly, steady pace. Your goal is to make yourself predictable to the drivers. I sort of knew this from previous travels but quickly re-learned this by initially following as close as humanly possible behind my guide as he crossed the streets until we separated days later and I had to take my life into my own hands. I can proudly say that I was never once hit by a car in Afghanistan.

Shortly after leaving the hotel, my guide and I passed through a book market section of the general market area. I wanted to stop and see what sort of Western books made it to Afghanistan (do they have Mein Kampf like in India?) but I was already noticing a lot of attention from bystanders toward me, and didn’t want to attract more by stopping. It was the very start of my Afghanistan trip, so I decided to try to keep a low profile until I figured things out here.

This decision clashed with my natural impulse to take pictures of everything when I travel. I had asked and clarified with my guide multiple times about what I could and could not take photos of, and I think I understood. As a tourist, it was generally fine to take pictures of anything except the Taliban, military things, government things, women, or children, and I had to be aware that using a DSLR camera would bring me a lot of attention. This was all fair, and pretty standard for a poor Muslim country.

So while walking down the street of Kabul, I had my phone out, and raised it above my head to grab quick pics, like this:

I was doing this for about one minute, after walking for about five minutes, after being in Afghanistan for about three hours, when a furious AK-armed Taliban guy started screaming his head off at me. We were standing in the middle of a market nexus where multiple walking streets converged, and there were a billion people around, and suddenly half of them were watching this Taliban guy scream in my face.

I had no idea what the Taliban guy was saying, so I just kept innocently shrugging and looking at my guide, who was standing next to me, a calm but concerned expression on his face, listening to the Taliban guy shouting in my face. I was briefly annoyed at my guide for not intervening more quickly, but as I was to learn, this was a deliberate and well-crafted strategy. He was really good at dealing with the Taliban, and he did so through this purposefully soft-spoken, approachable manner, which got him and me through more than one difficult situation.

When the Taliban guy finally stopped shouting, my guide finally began speaking in his trademark mild manner. The Taliban guy’s angry eyes darted back-and-forth between me and the guide. Then the Taliban guy barked something at me, and my guide told me to take out my passport. I did and gave it to the Taliban guy, while my guide went through his own bag and took out his tourist guide license, as well as a permit he had gotten from some ministry before I arrived to mark him as my official guide.

Then my guide spoke with the Taliban guy for five minutes, though he mostly listened. Throughout that time, random bystanders kept walking up to us. One shook my hand and said something to me. Maybe three or four briefly said something to my guide, sometimes whispering in his ear. One or two said something to the Taliban guy and were clearly annoyed.

The Taliban guy gave our papers back and said one final thing to me. He still seemed irritated, but he was calmer now, and he turned around and left. I asked my guide what happened, and he said the Taliban guy was angry at me for taking pictures. I replied that he (my guide) had told me that it was fine to take pictures, and he reiterated that it was, but this random Taliban guy didn’t know that. My guide said it was all fine, just don’t take pictures for a few minutes until we are away from this particular Taliban soldier.

I asked my guide what all the other people who approached us were saying. He explained that the ones who went up to the Taliban guy were scolding him, the one who went up to me was apologizing on behalf of Afghanistan, and the ones who went up to my guide were telling him to apologize to me and tell me that the Taliban were ignorant, and all guests should feel welcome in Afghanistan.

Undeterred, we walked around Kabul’s central marketplace for the next few hours. One highlight was the Bird Market, not to be confused with Chicken Street, which is also a well-known market, but only the former actually sells birds. It’s a pretty standard Islamic bazaar – narrow, all pedestrians, very crowded – and the merchants cluster by type, so there are 50+ rug merchants right next to each other, then 50+ merchants who sell pots and pans, and then 50+ merchants who sell shoes, etc. There were two merchants who sold animal skins, including wolves, foxes, and leopards:

And of course, they sell birds:

Right in the middle of the bird area, which is a particularly narrow and crowded street, there was a mass of people so thick that it blocked our way through, especially since they were all standing still. It was also the one part of Kabul so far where I wasn’t being stared at by 95% of the people who noticed me. As my guide and I wormed our way through the crowd, we eventually stumbled into the epicenter of the mob where two men were screaming at each other. One was covered in blood. I didn’t want to stop and take too much of a look since that would garner more attention, but I briefly saw blood stains clumped in maybe four or five spots on his chest and stomach.

Once my guide and I had cleared the mob, I asked him what the hell that was, and he said the bloody guy had been stabbed multiple times. I asked why, and he said he didn’t know.

Knifed guy aside, as we continued walking around for probably the fourth hour that day, it dawned on me how relatively normal Kabul was. This was the capital of a country that had been in foreign wars, civil wars, or in massive political upheaval almost continuously for about 45 years until 2021. And since then, its peace has been guaranteed by one of the worst organizations on planet earth.

And yet, Afghanistan, or at least Kabul, looked and functioned pretty normally for the capital of an impoverished country. People went to work, they prayed, they argued, they bought stuff, they had families. Even I could tell by clothing and faces that the different ethnic groups all mingled together. Despite the extreme economic privations of the country, you can still find Coca-Cola, potato chips, and cookies in every convenience store, and Pepsi in some, though, sadly, no Coke Zero. Restaurants commonly serve pizza, and some serve hamburgers or pasta, since all cultures eventually converge on these foods. Afghan traffic is terrifying, but people still get where they need to go, and drivers adapt. Afghan women are horribly oppressed, but you see them walking around. The Taliban are monsters, but they mostly seem pretty bored and they really do keep order.

Maybe this is a banal observation, but life goes on unless it really can’t. It reminds me of my time in Ukraine right after the war started. Even when Russia was in the process of invading Ukraine, a substantial portion of the male population had joined the military (voluntarily or otherwise), about 10% of the population had fled the country entirely, and another portion of the population had been internally displaced, most Ukrainians still lived their lives mostly normally in most of the country. They still went to work and cafes and restaurants and stuff. It wasn’t until I arrived in Kharkiv, which was then at the front line of the war, that I saw a city where life was completely different from normal. The city was about 95% empty, and everyone remaining either worked for the government or supplied it. If I had made it farther inland into Russian-controlled territory, like Bakhmut, then I would have seen cities that looked like something out of Central Europe in early 1945.

And so it is with Afghanistan. There are plenty of Afghans who hate the Taliban, hate what they’re doing to women, hate the economic situation in the country, wish the Americans or the warlords had won and taken over the country permanently (I frequently met people who believed all these things), and yet they still live normalish lives. Or at least they do as long as they don’t excessively run afoul of the Taliban.

In the late afternoon, my guide and I went to Kabul’s Blue Mosque. Like nearly all other turquoise-colored mosques, it is Shia (the Taliban and most of Afghanistan is Sunni), and in this case, largely used by Hazaras, an Afghan ethnic minority. And also like most other turquoise Shia mosques, it is insanely intricate and beautiful. IMO, the Shias have the Sunnis beat on the mosque game:

This was the first of many times in my trip that I would have to go through a Taliban checkpoint. The mosque was fenced off, and the entrance was guarded by two or three AK-wielding Taliban guys who patted entrants down to check for weapons. That might not be a bad idea since in 2018, ISIS killed 33 people here in a bombing. In what was to become a routine process, the Taliban guys looked at me coldly, spoke to my guide, he told me to give them my passport while he fished out his permit for me, they studied it all, gave it all back, patted me down, and then said a welcoming phrase. There were no problems, but after this first encounter, I learned to always greet the Taliban with a “salaam,” or, if I was feeling ambitious, the full-fledged “assalamu alaykum.” It made them a little bit nicer.

Immediately after passing the checkpoint, two old men with long beards in traditional (even by local standards) Afghan clothing came up to us and looked at me with intense fascination. They spoke to me in Pashto, which I obviously didn’t understand, so then they spoke to my guide. Through him, I answered some questions about where I was from and what I was doing here.

For the first of many times to come, they asked if I was a Muslim. I said I was a Christian, which isn’t true, but I always say I’m a Christian in Muslim countries. Muslims are generally cool with Christians – they are both Monotheists, both people of the Book, and both love Jesus Christ. Plus, Christians tend to have a bit of foreign, Western exoticism to them. I never told people in Muslim countries that I was an atheist, which could provoke hostility, and I also think it’s best not to experiment with claiming to be Jewish.

The two old men heavily shook my hand and said a bunch of stuff directly to me that I didn’t understand. I nodded and smiled and thanked until they walked off. Then I asked my guide who those guys were. He struggled at first to explain: “they are the men who hit women if they don’t cover their heads.” They must be the religious police. At least they were nice to me.

While walking around the Blue Mosque, my guide told me about how under the old US-backed government, it was common to see romantic couples here, even holding hands. Then, and in later conversations, he expressed gratitude to the Taliban for bringing peace to Afghanistan, and he even described the 2021-to-present political era as the best of his life. But that was solely due to the peace and safety; in most other regards, my guide opposed Taliban policy. He was a Muslim like everyone else, but on the secular side by Afghan standards (I never saw him pray). He was scared of the Taliban’s fundamentalism and lamented how “serious” they were about their beliefs. He was particularly worried about the futures of his two daughters, and, like so many other Afghans I met, he wanted to leave Afghanistan, ideally to live in the West, and even more ideally in the US, but he would settle for Pakistan.

Also while walking around the mosque, I saw a concentration of Hazaras for the first time. My guide said they “look like Chinese people” but they are really closer to Mongols, with the wider faces and slightly darker complexion. That night, over dinner, I asked my guide if the Taliban discriminated against the Hazaras or Shias. He said they didn’t; they could practice their religion and were treated like everyone else as long as they followed Taliban rules. I asked if the Taliban discriminated against any minority group or supporters of the previous regime; he said he didn’t. By his assessment, everyone was treated the same, and he commended the Taliban for that, if not their specific policies. This view was shared by some other Afghans I met, and strongly disputed by others.

What is the Taliban?

I’ll paraphrase a rough analogy Grame Wood gave in a podcast:

Imagine that the United States descended into a horrific civil war where the major states like Texas, California, and New York were led by ethnic warlords, and the rest of the country devolved into anarchic banditry that included widespread practices of the worst crimes imaginable. And then imagine that a group of radical Christian preachers in Appalachia banded together, declared one of their own the second-coming of Christ, raised a local army of nearly illiterate hillbillies, proceeded to conquer the United States, and replaced all the anarchic horror with their own brand of marginally less horrible theocratic tyranny.

That is very roughly the contextual trajectory of the Taliban. But to understand how that happened, you need to look at the not-so-recent ideological history of Islam. Namely, Islam has had a serious problem for the past 500ish years… it keeps losing.

Islam was started by Muhammad, an Arabian warlord who lived in the late 500s and early 600s AD, who claimed that god sent an angel to him to dictate the words of god by which all men should live for the rest of history. That’s a tall order for potential followers to swallow, but part of Muhammad’s pitch was that he, a random Arabian warlord, suddenly went on an extremely successful conquest spree that saw the first Islamic political state take over a big chunk of the Middle East. And then Muhammad’s successors proceeded to take over a big chunk of the earth with a domain stretching from Persia to southern Spain, while other believers brought Islamic armies to the far reaches of sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia. It was easy to believe that god really was on the side of the Muslims when they kept pulling off these incredible wins.

That all started to unravel around the 1500s or 1600s when the European Christians began to pull ahead of the Muslim powers technologically, economically, and militarily. By the 1700s, the Christians weren’t just pushing the Muslims out of Spain, but taking over really huge chunks of the globe, like nearly all of the Americas, India, and later Africa. By the 1800s, it was extremely obvious to any Muslim visitors to Europe that Christian societies, and even the more secular states, were simply doing better than the Muslim societies in so many respects and would likely continue to do so.

At the time, lots of Muslims, particularly in places like the Ottoman Empire, were asking the logical question – if god is with us and not them, why are they winning?

There are in-built Islamic explanations for this. In Muhammad’s time, when he was winning lots of battles and conquering lots of land, he also had a bunch of defeats, betrayals, and withdrawals. But of course, he eventually triumphed in the end, so by my understanding, the setbacks are justified as tests of the faithful to stay loyal to god and his plan, which will eventually lead to greater victories.

But considering the scope and scale of the Christian advancement past the Muslim states, more theory-crafting was needed in the Islamic world. In the Arabian Peninsula in the 18th century, Ibn Abd al-Wahhab developed what became known as Wahhabism, which preached that Islam had been weakened by decadence and straying from the original message of the prophet Muhammad, particularly by the likes of the Ottoman Empire, whose liberal Sufism devolved into mysticism and idolatry, and may as well be considered heresy. Wahhab proposed to strengthen Islam and the Muslim people by embracing a radical orthodox form of the faith based on replicating the lifestyle of the prophet Muhammad, who we should not forget was a 7th century warlord living in the Arabian desert. The nascent Wahhabi movement was adopted by the Saud family, who would go on to conquer Arabia and run Saudi Arabia quite proficiently.

In the Indian subcontinent, a similar but significantly more moderate movement was developed in the early 20th century in a city called Deobond in Uttar Pradesh, a particularly poor region in north-central India. This philosophy, which would become known as Deobondism, similarly preached that a handful of British soldiers had managed to conquer the colossal Indian subcontinent, including its vast Muslim minority, because the Islamic population had strayed too far away from the teachings of Muhammad. Deobondism spread and evolved throughout the subcontinent and was even brought abroad to places with large Indian populations like South Africa.

But Deobonism found its greatest following in the corner of the subcontinent that later became Pakistan, which had tens of millions of Muslims at independence in 1947, and has 250+ million Muslims today. In rural Pakistan, Deobondism became more radical and gained a closer resemblance to Wahhabism, including with a strong aversion to other sects of Islam and a hostility to liberal concepts like women’s rights. In Western Pakistan, the vast mountain desert region that borders Afghanistan, Deobondism was influenced by the Pashtuns, an already conservative Islamic people with a deeply-rooted tribal culture.

In the 1970s, Afghanistan’s monarchy was overthrown by Mohammad Daoud, then Daoud was overthrown by the communist Nur Muhammad Taraki, then Taraki was overthrown by the communist Hafizullah Amin, and then Amin was overthrown by a Soviet-backed regime, and then the Soviet-Afghan War erupted and would continue into the early 1990s. Throughout all this upheaval, millions of Afghans, particularly rural Pashtuns, fled their homes for the relative safety of Pakistan, where a friendly pro-Pashtun regime housed them in small towns and refugee camps along the border. The Pakistani Deobondi intellectuals flocked to these places, often with funding from the Pakistani government or wealthy Saudis, and set up madrassas.

Madrassas are Islamic schools. They can teach on a range of topics, but in the cases of these Afghan-Pakistan border towns, the madrassas were extremely simple. They taught basic literacy and Islam. Lots and lots of Islam – the Koran and the Sunnah, and maybe a little Islamic history. That’s it. It was not unheard of for students to memorize the Koran in Arabic despite having no fluency in Arabic. The teachers in these schools, known as mullahs, almost all received their own educations in similar madrassas, and therefore knew little besides how to read and write and about Islam. The Afghan refugees who fled to these towns and schools were overwhelmingly male, and the few girls and women were usually barred from the madrassas.

In the 1980s, particularly the late 1980s, more and more Afghans fled to these towns as the war raged on, but at the same time, Afghans steadily flowed back into Pakistan to fight as Mujahideen (basically rebels) against the communist Afghan government and its Soviet allies. These young soldiers were often orphans or didn’t know their parents, some had been born in these border towns, others had moved there when they were small children and didn’t remember their hometowns in Afghanistan. These were raised in these refugee camps, educated, and cared for by the mullahs and their madrassas. Most of these mullahs were radical Islamic Deobondists (sometimes called Neo-Deobondists) and aggressively encouraged their young students to join the Jihad in Afghanistan against the atheist communists. The best and brightest of the young men were sent to militant training camps built throughout the border region either by the Pakistani ISI or radical Islamist organizations, including what would later become Al Qaeda.

The vast majority of these young Mujahideen were Pashtuns since the Tajiks and Uzbeks would usually flee north to the Stans, and the Hazaras would flee west to Iran. These Pashtun warriors naturally joined the Pashtun Mujahideen factions based primarily in southern Afghanistan. These soldiers were badly educated in a traditional sense, and aside from the ones trained in the special militant camps, they didn’t know much about fighting, but they were fanatically devoted to their cause, and so, unlike the overwhelming majority of Afghan government forces, they were willing to charge machine gun nests to win battles.

In 1992, the Mujahideen won and the communist Afghan government fell. Within weeks, the Mujahideen factions began fighting each other and the Afghan Civil War broke out as a brutal clash between dozens of Mujahideen warlords largely based around ethnic and tribal lines. By that point, there were tens of thousands of these madrassa-educated Pashtun Mujahideen in Afghanistan, mostly based in the southern Afghan Pashtun territories. During the Civil War, even by the standards of the contemporary warlordism, the Pashtun territories were more chaotic than the rest, owing partially to Pashtun warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s rule (ex. he was one of the biggest pioneers of the Afghan heroin industry) and partially due to the inherently fractious nature of tribal Pashtun life. The countryside broke into hundreds of petty fiefdoms were localized warlords not only ran roughshod over the people in typical plundering manners, but also indulged in revenge plots based on new and ancient tribal rivalries.

You can’t understand the rise of the Taliban without understanding how bad the Civil War was. In 1994, Kabul was under the control of a nominal new Tajik-dominated central government, but it was also under siege and getting hit with artillery strikes every day by Hekmatyar, AKA the “Butcher of Kabul.”

Outside of the Kabul regime, there were no formal government structures. The warlords ruled by virtue of their wealth and military strength, and the exercise of their authority naturally descended by quasi-feudalist means, with power delegated to lieutenants who further delegated power to lower lieutenants, etc. This left most of the day-to-day civil administration of Afghan territory in the hands of random military commanders with little oversight from superiors who were usually busy fighting a war.

The result was thousands of Afghan towns being terrorized by petty tyrants who commanded small groups of soldiers. Looting, pillaging, extortion, rape, murder, and slavery were common throughout the country. If some small Afghan city was being horrifically brutalized by a local commander, say by having the local children rounded up for sex-slave harems, there was virtually nothing the civilians could do about it. Military resistance almost certainly meant death, either at the hands of the petty local tyrants or the reinforcements they might call in. Even if terrorized local civilians could somehow appeal to higher commanders or their warlord, such warriors had more important priorities than appeasing civilians, especially when their power was based on the support of mobs of disorganized soldiers whose de facto payments came partially in the form of pillaging occupied territories.

My use of “children” in the above sex slavery example is not an accident. Afghanistan and some of the other Stans have a history of bacha bazi, which is basically the practice of older men using young boys dressed and groomed to look like women for sexual satisfaction. Historically, sometimes the boys have been kidnapped, other times they were sold by desperate parents. While the practice has persisted in some form in Afghanistan for at least 2,000 years, it had a tragic resurgence during the Civil War when lawlessness was the norm.

A logical suggestion for Afghan civilians caught under the dominion of terrible warlords or their underlings would be to flee and live somewhere else, anywhere else. And indeed, hundreds of thousands (millions?) fled to Pakistan or Iran. But unfortunately, for many more millions, movement within Afghanistan somehow became even more dangerous than living under the warlords. With the complete breakdown of governing authorities, the territorial spaces between the warlords became completely overrun with bandit gangs, often consisting of current or former warlord squads.

In perhaps the most Mad Max-ish element of all, internal Afghan trade practically ground to a halt. Any trade or travel convoys moving between cities without significant armed support were easy prey for highwaymen. Initially, the gangs just robbed and killed everything they found. Eventually, these gangs coalesced into extremely expensive toll-collecting checkpoints, which loved the sight of United Nations or NGO trucks that were willing to pay, but most other travellers robbed or turned away. Keep in mind that the vast desert and mountainous terrain of Afghanistan usually only has one two-lane road between each major city, so separate gangs would set up their own checkpoints on single roads, necessitating paying off multiple factions on single trips.

(Rashid relates a story of travelling 120 miles from Quetta to Kandahar in 1993 and being stopped 20 times to pay extortions.)

So Afghanistan jumped out of the frying pan and into the fryer. Or, it jumped out of the destructive monodirectional civil war against a Soviet-backed communist government into the chaotic anarchy of multi-directional war between warlords. The masses of Afghan civilians lived at the mercy of arbitrary warlords, soldiers, and gangs who preyed on the populace in the worst possible ways imaginable. And with the warlords roughly equally balanced in power, there appeared to be no logical end to the fighting, especially with so many foreign powers dumping seemingly endless supplies of money and weapons into the fray. Afghanistan was in hell.

There are many levels in the debate over what is to blame for the Taliban ideologically. The first level is Islam, or at least radical Islam, since the Taliban claim to be embracing the truest form of Muhammad’s teachings. The next layer is Pashtun culture since the Taliban ideology is broadly a fusion of a strand of radical Islam and the most conservative elements of the Pashtuns. If you push down yet another layer, there are people who say it isn’t Pashtun culture to blame, but specifically the culture of the Durrani, a large Pashtun tribe that historically ruled Afghanistan going back to the 18th century.

Sometime in mid-1994, amidst the chaos of the Civil War and particularly the Pashtun south, a group of Durrani Pashtun Mujahideen gathered in Kandahar and agreed to form a new faction. These men held special authority among the Mujahideen because they were mullahs. They all taught at madrassas in rural Kandahar, thus making them sort of warrior priests. They called themselves the “Taliban,” which is a merger of an Arabic word adopted into Pashto and combined with a Dari (Persian) word, all of which combines to mean “Students,” as in “Students of Islam.”

Their stated aim was to restore order to Afghanistan. This was to be done by defeating the warlords and establishing a new government based on a strict, radically conservative implementation of Sharia law so Afghans would live as Mohammad did in Arabia 1,400 years ago. Non-Muslims, who would include Shias and insufficiently orthodox Sunnis (like Sufis) in their view, would be converted or driven from the land, along with communist and Western influences. Though the Taliban themselves would say that the prophet was their only guiding force, observers would claim that quite a bit of Pashtun and Durrani culture seeped into their guiding directives, particularly regarding their proposed legal structures and treatment of women.

The leader chosen among the Taliban was Muhammad Omar Mujahid, henceforth known as Mullah Omar. Like the rest, Mullah Omar was born into rural Pashtun poverty and had almost no education beyond basic literacy and advanced Islam. He had fought as a Mujahideen, quite well by many accounts, and had lost his right eye in the process. He was said to be soft-spoken, shy, and an outright bad public speaker. By Rashid’s account, Mullah Omar was almost entirely chosen for leadership on the basis of his piety, rather than his intelligence or charisma. Surprisingly, this played to the Taliban’s advantage as Mullah Omar was able to situate himself as a lofty figure who could stay above the fray of Pashtun politics waged by his subordinates, and he could consistently operate as a unifying force for the entire Taliban organization. However, by Malkasian’s account, “original members of the Taliban often described him as a ‘simple man.’ A few went so far as to call him stupid.”

Rashid compares Mullah Omar’s leadership style to that of Pol Pot. Like the Cambodian communist, Mullah Omar was oddly shadowy and mysterious despite having tremendous personal authority in his political movement. He left almost all the day-to-day management of the Taliban to subordinates while he would hang out in the background and occasionally weigh in on contentious matters, using his reputation for flawless piety to sway the organization. He was said to be quiet and patient in meetings. There is only one known photograph of adult Mullah Omar, and he is a reported 6 feet, 6 inches tall. He didn’t have a central base; he constantly traveled between rural villages, and communicated with lieutenants via personal couriers who carried scraps of paper with his hand-written decrees. All of his underlings down to the lowest rank-and-file soldier knew who he was, but only his top lieutenants knew anything about him. To everyone else, he was this distant, aloof, mysterious entity who hovered above them all but didn’t dirty himself with grubby politics and warfare. Though one thing he did dirty himself with was financial management; the Taliban’s central treasury was literally a metal box filled with cash that Mullah Omar carried everywhere and usually kept under his mattress.

Even in Kandahar in 1994, there weren’t that many AK-47-wielding warrior priests; the Taliban leaders needed to recruit foot soldiers to wage their holy liberation of Afghanistan. They found their men (and they were exclusively men) in the form of the legions of young Mujahideen who had been raised in the Afghan-Pakistan border region and educated by Deobandi mullahs. In time, a pipeline was established to directly funnel a whole new generation of zealot warriors into the Taliban ranks.

In 1994, Kandahar City (the capital of Kandahar province) was under the reign of a particularly brutal Pashtun sub-warlord who was systematically stripping the city of every scrap of wealth, including selling off industrial equipment, to pay for the war effort. The various villages around Kandahar City were under the control of sub-sub-warlords who were doing the worst things imaginable.

In this context, the Taliban first appeared on the scene as vigilantes. They would receive reports of warlord wrongdoing, deploy a squad of fighters, usually kill a bunch of soldiers, capture the commander, and then publicly execute him and leave his body for all to see. The Taliban especially pursued purveyors of sex crimes, like commanders who kept stables of bacha bazi boys abducted from the locals. Punishments were Biblical (well, Koranic) – decapitations, cutting off hands, hanging bodies, etc.

While the Taliban took requests, they didn’t accept payment. They didn’t stick around either; they responded to calls, dished out justice, and then left the bodies behind. Rashid describes the Taliban as developing a Robinhood-esque reputation, but it was more than that. The Pashtun population living under the thumbs of the warlords were deeply religious themselves, and the Taliban swept in as a force promising divine retribution against the evilest men imaginable. It’s not hard to see how they developed a following.

However, the Taliban needed money to equip, house, and feed their growing army, and since they weren’t charging the local population and refused to engage in plundering like the rest of the warlords, they needed another revenue source. This was one of my biggest surprises in learning about the Taliban. A key player to the rise of one of the worst regimes on earth was… teamsters.

As mentioned, by 1994, the Afghan road network was thoroughly plagued by warlords and bandits preying upon the sparse traffic between major cities. This left the Afghan trucking companies dead in the water. Sometimes they could afford the dozens of extortion payments per route, or sometimes they could align with one warlord for ongoing extortion payments, but mostly the trucking industry as a whole shut down.

But in Kandahar, there were these new Taliban guys who seemed to be getting shit done. And unlike the warlords, they were honest in their dealings due to their deep religious convictions. So the truckers began contracting with the Taliban to protect their convoys or even clear the roads of bandits and checkpoints entirely. And just as with the vigilante raids, the Taliban turned out to be very good at this. Soon enough, trade was opening up in Kandahar, and then the surrounding provinces.