I wrote about the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs five years ago during the early days of this blog. The conquistadors have since remained a fascination of mine, but I haven’t had a chance to go back to them until recently when I read Bernal Diaz’s The Conquest of New Spain and then The Last Days of the Incas by Kim MacQuarrie. My goal was to get a thorough understanding of the two major Spanish New World conquests and how small Western military forces achieved such stunning successes over gargantuan native empires.

In the case of Hernan Cortes, about 400 Spanish soldiers (later increased to over 1,000) subjugated the Mexican Empire of about 6 million inhabitants. In the case of Francisco Pizarro, about 180 Spanish soldiers (eventually rising to over 1,000, but with rarely more than 500 ever concentrated in one place) conquered the Inca Empire of maybe 10 million inhabitants. In both cases, the Spanish invaders had almost no understanding of the local politics, geography, culture, religion, or people they were invading. In both cases, the expedition leaders deserve a ton of credit for extraordinary leadership and competence while leveraging a technological imbalance to achieve a staggering military force and diplomatic multiplier.

Since I already wrote about the Aztecs, this essay is primarily focused on Pizarro’s conquest of the Incas, which, as a reader, I found no less insane, exciting, ridiculous, and fascinating based on MacQuarrie’s fantastic The Last Days of the Incas. I want to present the most straightforward account of what happened and why with enough detail to get a sense of the difficulty and enormity of the conquest, but pared down enough to make the story digestible. I’ll also intersperse some of the most interesting points I learned from The Conquest of New Spain, which is translated from a first-hand account of one of the conquistadors present at the invasion of the Aztec Empire. At the end, I reflect a bit on why I find this stuff so interesting and can’t stop thinking about it.

The Incas

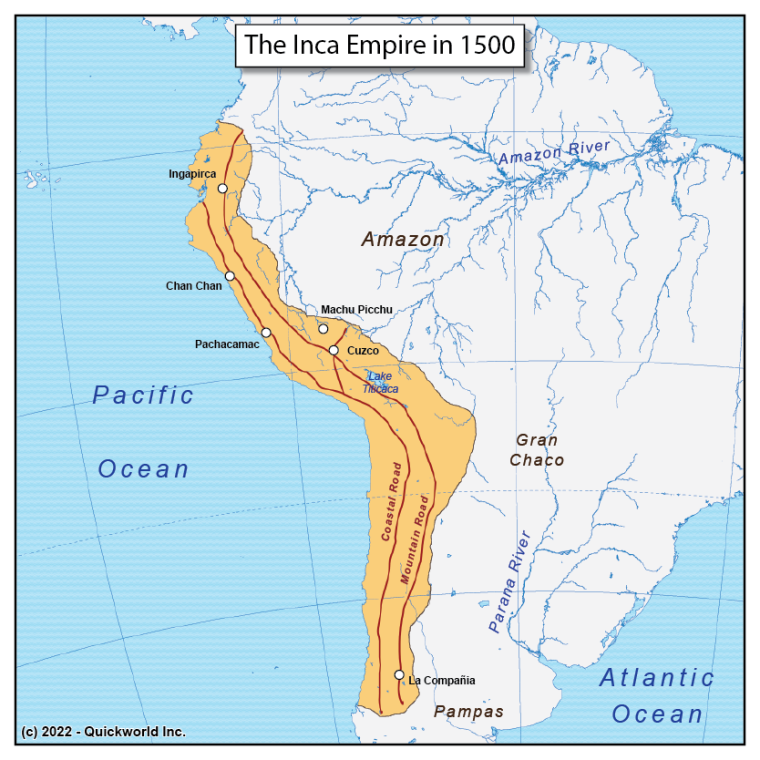

The Incas were/are an ethnic group based around Cusco, a city that sits at an elevation over 11,000 feet (3,300 meters) in what is today inland Peru. At the height of their power, a mere 100,000 ethnic Incas dominated an empire of 8-10 million inhabitants stretching from southern Colombia to northern Chile, from the edge of the Amazon rainforest, over the Andes, and to the Pacific coast. In the 16th century, Cusco’s population may have been as large as 200,000, making it comparable to Paris at the time. They called their country/nation/state/whatever you want to classify it: Tawantinsuyu.

When Francisco Pizarro first arrived at Incan land in 1528, the Incas had only expanded outside the Cusco valley for about 200 years, had only been a genuine empire for about 100 years, and had conquered most of its territory over about the last 60 years. Their expansion stopped not due to any failings on the Incas’ part, but because they had beaten every significant civilization in their vicinity, and all that was left on their borders were small villages and disorganized nomads in dense tropical jungles or sparse mountain ranges.

If there was a secret sauce that gave the Inca an edge over their neighbors, it was probably organization. Their civilization was based in fertile valleys nestled between some of the tallest mountain peaks in the Western hemisphere. They got good at terrace farming, roads, transport, communication, infrastructure, and other logistics that permitted the formation of larger armies than their competitors.

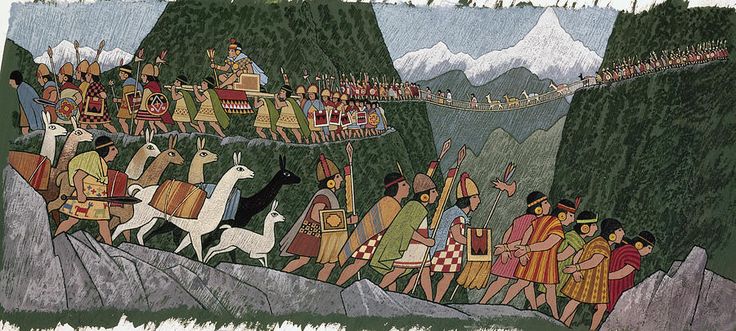

It helped that the Incan conquest modus operandi was relatively indirect. The standard procedure was to bribe, threaten, or fight rival city-states into submission, then decapitate or co-opt the leadership, and then install Incan governors while keeping much of the prior state apparatus intact. The Incas preferred to harness long-term productive yields from populations in new territory rather than indulging in plunder. In lieu of taxes, every able-bodied adult male in the Incan Empire was legally required to work for the state for three months per year, or at least send their wives or children in their stead. This mass of labor, which eventually reached into the millions, produced potatoes, meat (llama or alpaca mostly), wool (same), gold, and other goods for the state, as well as building its palaces and extensive road system. Seemingly much more so than the Aztecs and comparable civilizations, the Inca understood that their power was based in its people and their production.

There is a part early in Conquest of New Spain when Bernal Dias describes walking into a village and finding a pile of disemboweled native bodies that had been recently ritualistically sacrificed, and then Dias says that such sights were so common in so many villages that he is going to stop describing them, but that the reader should just assume that the Spanish always encountered such spectacles in every single Mesoamerican village or city they entered.

The Incas also did human sacrifices, but nowhere near to the same extent. MacQuarrie mentions it a few times but there were no piles of mutilated bodies in every town. However, the Incas seemed particularly fond of child sacrifices through a practice called capacocha. Like the Aztecs, the Incan leaders demanded periodic tributes from each region of the empire, though giving up a child to be sacrificed was considered a great honor.

I don’t have a great sense of the technological differences between the Incas and the Aztecs, but for a few points of comparison:

- The Incas had better infrastructure, most notably their road system which ran at lengths estimated between 14,000 miles and 37,000 miles, snaking through the aforementioned mountain ranges, rainforests, deserts, etc. The Inca government developed a crazy messenger system where runners trained at high altitudes ran relays to deliver messages across the empire at the maximal speed of human beings on foot. There was also the qullqa system of warehouses that stored the surplus wealth of the Incan government. MacQuarrie describes endless piles of gold and cloth and food stacked in these buildings.

- Unfortunately, one of the reasons the Incas had to stack their wealth in buildings was because they had no monetary system. The Aztecs hadn’t quite figured out a centralized currency, but a few common goods like cocoa beans emerged as de facto currencies in their marketplaces. It’s almost kind of more impressive that the Incan empire of maybe 10 million people got by on the barter system.

- Likewise, the Incas were behind the Aztecs when it came to writing. The latter hadn’t developed a formal writing system, let alone an alphabet, but they had a pictographic language and paper to put it on. The Inca had no writing system nor paper; they relied on quipus, or “knotted cords,” that they tied in certain ways to record numbers, which at least permitted some basic accounting.

- Metallurgy was a slight edge for the Incas. Neither civilization had iron, both had copper, but the Incas used it more widely than the Aztecs. Most notably, the Incas incorporated bronze (a copper alloy) in their weaponry, though to a relatively small extent, like bronze-tipped spears. The Aztecs only used copper for civilian purposes and stuck mostly to the extremely sharp but brittle obsidian for their weaponry.

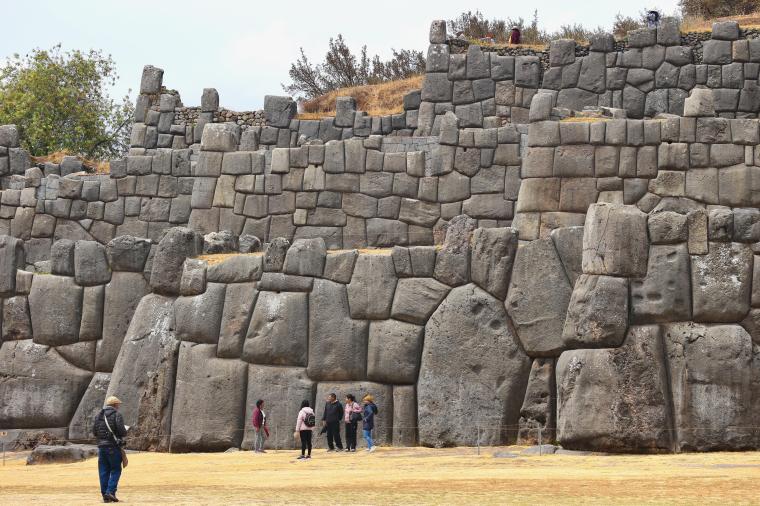

- I’m not sure who had the edge in engineering. No city in the Western hemisphere coming close to the size and sophistication of Tenochtitlan, but the Incas managed to carve, lift, and transport colossal stones to the top of mountains to build Machu Pichu and other sites.

- The Incas were ahead in animal husbandry with domesticated llamas and alpacas used for meat, clothing, and material transport (though, sadly, llamas are not big enough to be purposefully ridden). The Aztecs had domesticated turkeys, ducks, and dogs, but there were no tamable large mammals nearby.

- While it’s more subjective, I’d also give a slight edge to the Incas in terms of government organization. The Mexican Empire was basically a city-state (Tenochtitlan) with two junior allies (Tetzcoco and Tlacopan) forcing a cluster of nearby city-states to pay tribute. The Incan Empire, while decentralized by contemporary European standards, had a more integrated national government with Incan elites deployed across the lands to oversee territories as governors.

The Incan Empire peaked during the reign of Huayna Capac (who is well-known as objectively the best leader in Civilization IV due to his combination of Financial and Industrious traits). Huayna Capac ascended to the throne at age 5 in 1493, at which point the Incan Empire’s borders had almost reached their peak. Throughout his 34 year reign, Huayna Capac was mostly focused on consolidating gains into a lasting legacy, which is no small feat for 100,000 Incas trying to control a territory larger than modern Mexico. His successful efforts in formalizing the Incan government structure and improving the empire’s infrastructure made Huayna Capac a legendary figure during his time and afterward, sort of analogous to Caesar Augustus in ancient Rome.

Little did the Inca know that the end of Huayna Capac’s reign was the beginning of the end of the Inca Empire. In 1528, Francisco Pizarro discovered the Incas while on an expeditionary sailing venture south from Panama. Some of his men briefly went ashore at the city of Tumbes in northern Peru where they learned that the Incan Empire was a thing and that it was ruled by the mighty Huayna Capac. Pizzaro’s expedition then turned around and went back to Panama so Pizarro could prepare a proper invasion expedition and ask the King of Spain for permission to do so. Weeks later, Huayna Capac died of smallpox, which originated in Spanish settlements along the north coast of South America and tore its way north-to-south. The total estimated death toll in the Incan Empire was around 200,000.

Incan succession was similar to Mexican (Aztec) succession. Both governments were monarchies, but both the formal and informal rules around which son inherited the throne were a lot more fluid than in Europe where by that point, most states had primogeniture, or a system where the oldest son inherits most or all of his father’s titles.

In the Inca Empire, it was more complicated. The Incan Emperor, like all Incan men, could have multiple wives and concubines, all of whom might produce heirs. But the first wife was given special status and only her children were considered to be of full royal blood. Thus it was from her children that the emperor was expected to choose a son to succeed him. However, the legitimacy of a given heir was more of a sliding scale. The son of the first wife chosen by the Emperor had the most legitimacy, but every other son of the first wife also had some legitimacy, and every son of every other wife and concubine also had some, albeit less, legitimacy.

So, what ultimately decided the matter of succession? As with the Aztecs and Ottomans, it came down to warfare and intrigue. The most ambitious heirs were expected to form alliances with weaker sons and then fight each other in civil wars or murder each other covertly until there was one viable heir left. According to MacQuarrie, “the difference between European and Inca versions of monarchy… was that among the Incas bloody dynastic struggles were expected.” They saw it as a meritocratic process for finding the best heir.

(Incidentally, brother-sister marriage was illegal throughout the Incan Empire but was considered a divine practice for the Incan Emperor, so a lot of the heirs involved in these struggles were inbred.)

On his deathbed, Huayna Capac designated his oldest son, Ninan Cuyochi, as his heir to a group of leading nobles. Huayna Capac succumbed to smallpox, the nobles went to Ninan Cuyochi, and found he was also dead from smallpox. Fortunately, Huayna Capac had designated a second heir, Huascar, though he didn’t seem like the smartest choice. MacQuarrie says he “had little interest in military affairs, drank to excess, commonly slept with married women, and was known to murder their husbands if they complained.” Also, his mother was his aunt.

A pretender immediately rose up in the form of another son, Atahualpa, who had accompanied his father on numerous military campaigns and took a liking not just to warfare, but command. He was known to be severe and haughty even by Incan noble standards. He launched his insurrection from Quito in the poorer north and controlled less territory than Huascar, but had more of the military and the senior command staff on his side. The lackadaisical Huascar set himself up in the capital of Cusco and launched his armies north to capture or kill Atahualpa, thus starting another Incan succession war.

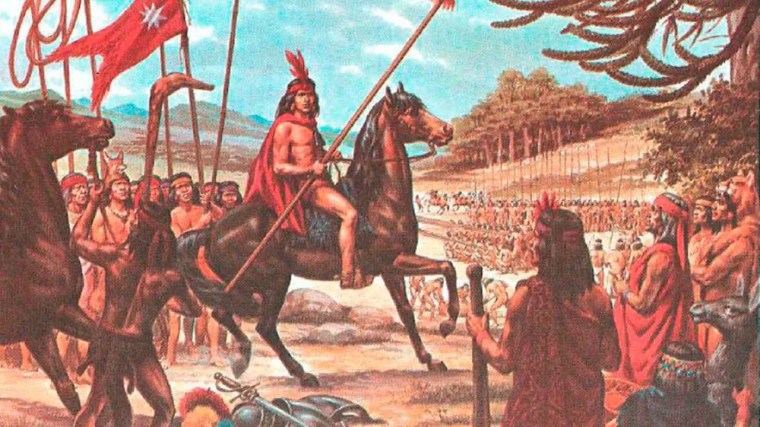

Fighting lasted for four years with Atahualpa gaining the upper hand, pushing his armies south while eliminating pockets of pro-Huascar resistance, and finally cornering Huascar in Cusco in 1532. Huascar was killed and the civil war ended only a month or two after the second arrival of Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish expedition.

The Spanish

In 1478, Francisco Pizarro was born in the city of Trujillo, in the region of Extremadura, which was the poorest part of Spain (and it still has the lowest GDP per capita on the Spanish mainland). His father was a low-tier noble and his mother was an unmarried commoner, making Pizarro a bastard. Like most of his future expedition members, he received little-to-no education and was a life-long illiterate.

At Pizarro’s age 15, Christopher Columbus returned to Spain from the Americas. Generations later, many of the early settlers of Jamestown and other colonies in North America were the second sons of nobility and noble bastards who grew up close to wealth but knew they would never have their cut of it due to their circumstances at birth. Likewise, hundreds of similarly-positioned Spaniards found the New World frontier to be a high-risk, high-reward shot at glory and wealth. At age 24, Pizarro was one of the “impoverished, illiterate, and title-less” adventurers who signed up for an expedition to the Caribbean in the name of the Spanish King.

Pizarro spent the next 25 years adventuring throughout Central America in an impressive display of avoiding death by disease or violence. At first, he bounced around as a man-at-arms for any expedition that would take him, and he cut his teeth killing/enslaving natives on Caribbean islands and the South American coastline. His first claim to fame was being part of Vasco Nunez de Balboa’s 1513 expedition which discovered the Pacific Ocean by crossing Panama on-foot. He then established himself as a member of the governor’s administration in Panama, later participated in a coup to overthrow the governor, and then leveraged his elevated post to organize further excursions mostly into South America.

By all accounts, Pizarro was highly competent and quite good at conquistadoring. MacQuarrie describes him as “brave, firm, ambitious, cunningly diplomatic,” and “as brutal as the situation requires.” He was also “quiet, taciturn,” and generally “did very little talking but was strong on action.” However, he was good at making speeches when one was called for, including both in battle and diplomatically. Physically, he was “tall, sinewy, athletic, with hollow cheeks and a thin beard,” and he resembled Don Quixote (though the story was not written until after his death). Pizarro was a very good fighter, but a mediocre horseman, and so, unlike most elite conquistadors, he preferred fighting on foot.

And yet, for all his talents, after 25 years of conquistadoring, Pizarro had never quite hit it big, though he had done alright for himself. He had to be considered at least one of the best conquistadors in in the New World after so many successful ventures. He had collected enough wealth through wages and looting minor native settlements to deck himself out in armor and modern weapons. But he wanted more. He wanted to conquer some big native state, loot it for all it was worth, and then set himself up as a dynastic governor to milk for the rest of his life.

MacQuarrie describes the conquest of the Mexican Empire by Hernan Cortes as almost provoking an existential crisis in Pizarro. Cortes was another poor, illiterate (though legitimate) low-tier noble from Extremadura, and he was even a second cousin once removed from Pizarro. After only 15 years in the New World, Cortes had accomplished by far the most successful conquistador expedition in Mexico, rendering himself absurdly wealthy, absurdly glorious, and a Crown-approved governor of a gargantuan piece of land at age 34. By that point, Pizarro was already 43 and had never reached those heights.

With his already sizeable ambitions further inflamed, Pizarro launched his own expedition corporation called the Company of the Levant to find and make a Mexico-sized conquest. His business partner was another key player in the Incan conquest: Diego de Almagro, another illiterate bastard of low nobility, but with an even more “sketchy” past.

Early in his life, Almagro was abandoned by his mother, then taken in by his noble father, who gave him up to his brother (Almagro’s uncle), who horribly abused him in medieval ways, like chaining him up in a cage. Almagro ran away from home at age 15 and went back to his mother, but she refused to take him in, so he spent the rest of his adolescence on the streets as an orphan. At some point, he moved to Toledo, stabbed someone, fled justice to Seville, and then hopped on a ship to the New World at age 39. He spent a decade conquistadoring around Panama and Colombia, and like Pizarro, found decent but not Cortes-tier successes.

Almagro was ugly, short, fat, and conceited, but courageous and generous to his men. During one of his expeditions, he lost an eye and subsequently always wore an eyepatch. When Pizarro and Almagro joined forces in 1524, the former was a spry 46 and the latter was a sputtering 49. But they each served their roles: Pizarro was the frontman with more military experience and skill who would lead things on the ground, while Almagro was the planning, logistics, and business guy who would get everything set up.

In 1524, the Company of the Levant made its first expedition, a little scouting trip south from Panama along the Colombian coast with 84 men to chase rumors of a gigantic native kingdom. The expedition soon stalled out due to poor planning and bad weather.

In 1526, they launched a second expedition in the same direction with two ships and over 160 men. They messed around the Colombian coast for awhile and eventually reached Ecuador where they once again ran out of supplies. The expedition split with Almagro taking the lion’s share of men back to Panama, and Pizarro going on with the only 13 men who volunteered to stay with him. It took almost two years for them to finally reach Tumbes, a coastal Incan city with the architecture, city planning, and wealth to indicate that it was worth conquering. Cortes and his men exchanged gifts with the locals and were even (voluntarily) given some boys/servants/slaves who would be raised as translators. Pizarro then returned to Panama with a plan.

Pizarro would go all the way back to Spain for the first time in 25+ years to meet with the King and ask for a royal license to conquer this Incan Empire and become its governor. Meanwhile, Almagro would hang back in Panama and organize the next expedition, which would be larger, better equipped, better supplied, and cost way more than the previous expeditions.

Both men succeeded. Pizarro was hailed as a celebrity as he presented his tales and gifts (including a llama) to the Spanish court. King Charles I, having recently absorbed the incalculable riches of Mexico, was happy to grant a conquest license to another ambitious Spaniard. The only catch was that Pizarro was on his own with financing, which was to be expected. Notably, it was Pizarro specifically who was granted the governorship of Peru, while Almagro was officially given no title besides the Mayor of Tumbes. Before heading back to the New World, Pizarro picked up a bunch of eager adventurers for the expedition, including three half-brothers aged 29, 18, and 17, who would serve as lieutenants.

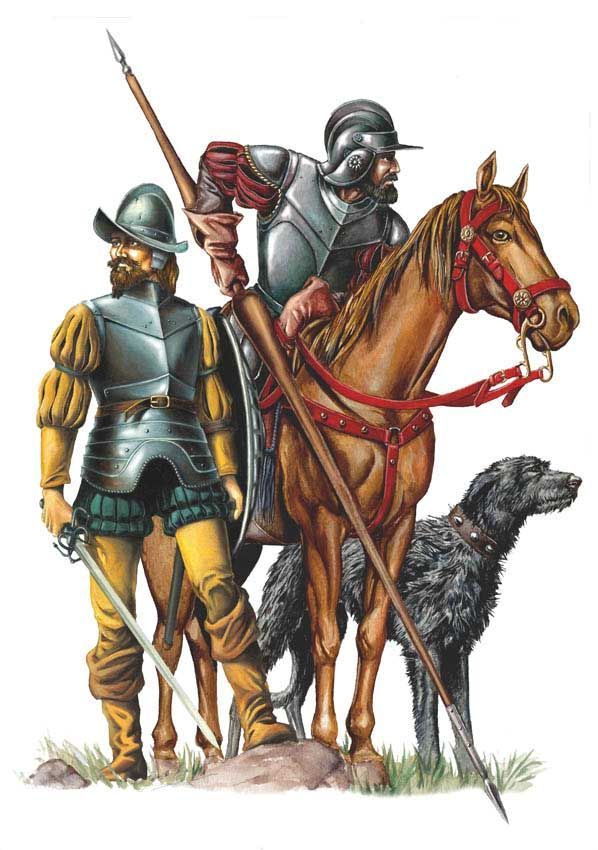

In 1532, the four Pizarros set sail from Panama with a total of 168 soldiers, with 62 cavalry (wielding 12-foot lances), about a dozen harquebuses (big, clumsy guns, more primitive than a musket), and four cannons. Individual soldiers were promised a cut of the loot based on their rank which was based on their experience and the quality of equipment they brought (cavalry at the top, basic foot soldiers at the bottom, harquebuses and crossbowmen in the middle). The army was led by the 54 year old Francisco Pizarro while the 57 year old Almagro stayed back in Panama to raise a second wave of soldiers.

Pizarro’s initial army was not an organized military unit, but rather a band of adventurers thrown together, so both the weaponry and armor was haphazard. All soldiers were equipped with at least iron chainmail, though most had at least some plate covering, often cuirasses that covered the torso. Helmets were also universal, though they usually left the bottom of the face uncovered. The horses usually had thick padded cotton to serve as an effective defense, though there was some cavalry plate armor as well. Also, pretty much all infantry had shields as a first-line of defense before the armor.

(Shout out to the forums on myarmory.com, a delightful holdover from pre-Reddit days when enthusiasts gather to discuss their nerdy hobby. I read through a ton of threads on conquistador weaponry and armor.)

A few of these conquistadors had been professional soldiers or mercenaries back in Europe, a few more had been on other expeditions in the New World, but most were poor, ambitious men of varying normal professions (ex. sailors, merchants, blacksmiths, masons, etc.) basically buying a lottery ticket for their own cut of the fame and fortune of a successful New World conquest. Many of these soldiers had bought their equipment on credit from crafty New World merchants. In addition, there were a handful of camp followers, including a priest, some African slaves, some female Muslim slaves, and some of the aforementioned merchants who continued selling goods on credit while on campaign.

Beachhead

After leaving Panama, Francisco Pizarro’s expedition skipped the usual messing around in Colombia and Ecuador, and went straight to Tumbes, the coastal Inca city, But to his surprise, Pizarro found it in ruins. Many of the very-well-made-for-a-native-city buildings were burned down and bodies littered the streets. Pizarro soon learned from a surviving local through his now teenaged translators that Huayna Capac was dead, the Incan Empire was in a winding down civil war, Tumbes had sided with Huascar, and Atahualpa had punished the town for it.

This was a disappointing start to the venture. Pizarro, had… I guess not read, but somehow absorbed the many first- and second-hand writings of Cortes’s Aztec conquest, and planned to use it as a playbook for his Inca conquest. Cortes had arrived at the edge of the Mexican Empire, allied himself with Aztec rivals and vassals through war and diplomacy, and made his way to the capital city of Tenochtitlan with their military support and literal geographic guidance. But that general strategy wasn’t really viable so far in Peru. All the people Pizarro thought he could use to get to the center of the Incan Empire were either killed by civil war or smallpox.

So Pizarro pivoted. First he set up a little settlement, San Miguel de Piura, and garrisoned it with 50 men. Then he collected some incoming reinforcements from Panama (but still no Almagro), bringing his soldier count up to 168. Then Pizarro raided a few towns, captured some locals to use as slaves, and tortured some others to learn about the Incan Empire and how to get to its capital of Cusco. After perceiving that one village chiefs was lying to him, Pizarro ordered a bunch of natives to be burned to death as a warning to the others.

(It’s worth noting that despite Cortes’s reputation for brutality, he doesn’t do anything this brutal until about six months into his expedition when there’s a local revolt against his rule and he orders his men to cut a bunch of prisoners’ hands off.)

After a few weeks of meandering terror tactics, Pizarro received an emissary from the pretender Emperor Atahualpa. By this point, he was pretty much the real Emperor, as one of his armies was marching on a nearly defenseless Cusco to finally depose and murder Emperor Huascar at the end of the four-year civil war. Through the impressive Incan runner messaging system, Emperor Atahualpa had been receiving reports of bizarre foreigners, noted for their massive beasts, shiny armor, paleness, and especially their beards, which apparently didn’t exist in Peru. He was also amazed by reports that the Spaniards didn’t need to sleep (probably a misunderstanding of Spanish sentry-posting at night), could eat gold and silver, used silver weapons (because they didn’t know what iron was), and that they spent much of their time talking to symbols on flat things (ie. reading).

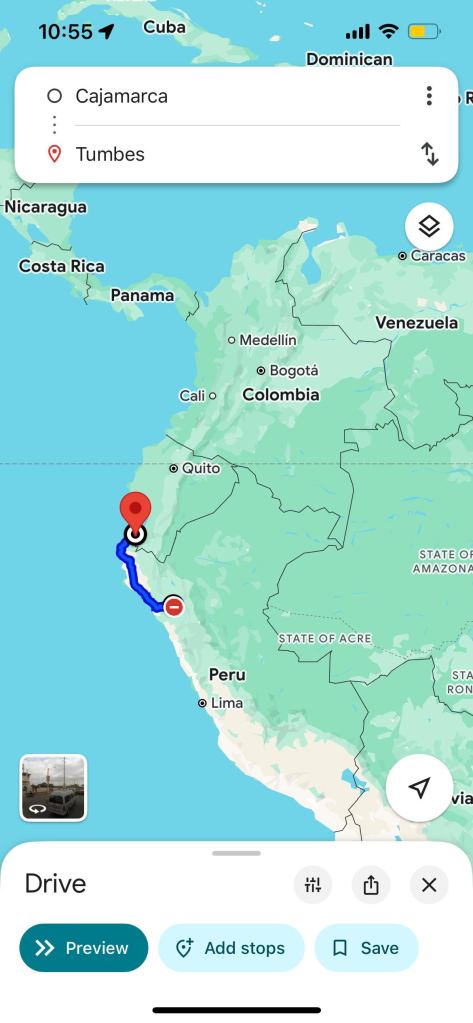

Emperor Atahualpa had also heard that they had been torturing and murdering his subjects for seemingly no reason. According to MacQuarrie, Emperor Atahualpa sent his emissary to the Spanish to invite them to meet him at his encampment near the city of Cajamarca, where the emperor would get to see these strange foreigners, then probably kidnap, enslave, and castrate them. Then they could be a cool little court exhibit when he took up the throne in Cusco.

Things were now looking up for Pizarro. It had taken Cortes seven months to meet Emperor Montezuma, but Pizarro was invited to meet the Incan Emperor within the first few weeks of his expedition. All he had to do was march about 200 miles inland while ascending 9,000 feet (2,750 meters) into a land he knew absolutely nothing about.

When Pizarro and his 167 soldiers reached Cajamarca, they found an army of somewhere between 30,000 and 80,000 Incas camped outside the city in an endless sea of tents. MacQuarrie describes it as a genuine “oh shit” moment for the conquistadors. They may have heard the stories of Cortes’s army beating native forces 100X+ larger, but actually seeing armies that big brought them face-to-face with reality. They really could just get overwhelmed and slaughtered at first contact. This giant empire of maybe 10 million people actually could kill/torture/enslave them all. The only thing standing between the Spaniards and annihilation or agony was about 168 of each other.

With Emperor Atahualpa and his army camped outside the city, Pizarro maneuvered his men into the city center and set up a base of operations. The Spaniards were impressed by the quality of the stone buildings and used them for shelter instead of their tents. Soon after, Pizarro decided to make contact with the Incan Emperor, and so he deployed one of his top cavalry lieutenants, future famed conquistador and first European to cross the Mississippi River Hernando De Soto along with one of the teenaged translators. Then, for some reason, 15 minutes after sending de Soto, Pizarro also sent his oldest brother, Hernando Pizarro, after them.

MacQuarrie calls De Soto a “wise choice” for serving as Pizarro’s diplomat since he was probably the second-most experienced conquistador in the group. But MacQuarrie also describes De Soto as “brash and impudent, having killed countless natives in hand-to-hand combat,” so I’m not sure about that. The Incas had no horses and had never seen an animals that big in their entire empire’s history, so of course De Soto proceeded to gallop through the Inca camp shouting for directions to find the Emperor at bewildered Incan warriors.

When he found the Emperor set up in a courtyard, de Soto charged up to him so quickly and with such a sudden stop that the Emperor’s clothes fluttered in a gust of air. In a scene that sounds so cool that it beggars belief, Emperor Atahualpa neither flinched nor looked up from the ground in a display of stoic awesomeness. Incan nobility were expected to be extraordinarily condescending and haughty towards subordinates, and Atahualpa was considered to be S-tier in this trait.

De Soto then went into a lengthy speech to the Emperor about how there were two emperors ruling the civilized world: the Holy Roman Emperor, who was also the Spanish King, and the Pope, who was god’s chief agent on earth. In 1493, the Pope assigned all land west of the Tordesillas meridian to Spain, and therefore the Incan Empire was Spanish territory, and so Emperor Atahualpa and his nobles should pledge their fealty to King Charles and convert to Christianity. This was all transmitted by a teenager with a shaky grasp of Spanish and who had barely spoken his native Incan language in four years, so I like to imagine that it went down like a newly immigrated ESL foreigner trying to explain the plot of sci-fi space opera to a geriatric.

Emperor Atahualpa continued staring at the ground and not acknowledging the presence of the Spaniards. This continued awkwardly until the arrival of Hernando Pizarro, who was somehow an even worse choice for a diplomat. Not that he didn’t have his virtues: he was strong, an excellent fighter, extremely brave, and would later prove himself as an incredible military leader. But he also had a reputation for being an extraordinarily arrogant asshole, to the point where even after successfully leading men through harrowing military endeavors and saving many of their lives, they still hated his guts. MacQuarrie gives him the unenviable title of the “least popular of the Pizarro brothers.”

When Hernando Pizarro introduced himself, Emperor Atahualpa finally looked up. He asked Hernando why the Spaniards had been burning Incan subjects alive. Hernando replied with some legalistic arguments for self-defense and then accused one of the native chiefs they had burned to death of being a “scoundrel.”

They stood around awkwardly a bit more, and then De Soto, the allegedly superior diplomat, noticed that Emperor Atahualpa seemed to be purposefully avoiding looking at their horses despite how mind-blowing they must have been. So De Soto decided to get his attention by making his horse rear back on its hind legs and stomp on the ground with a great snort. Amazingly, Atahualpa didn’t budge nor look at the horse, but a bunch of his royal bodyguards freaked out and ran away. Later that day, they would all be put to death by the Emperor for cowardice.

(There are many cinematic moments in Last Days of the Incas, but this whole negotiation feels the most like something written for a movie.)

A few more words were exchanged, and Hernando Pizarro invited the Emperor to meet Francisco Pizarro in Cajamarca the next day. Emperor Atahualpa assented, but after the Spaniards left, he told his advisors that the meeting had solidified his plan to capture and castrate the Spaniards, and also to capture and breed some horses.

Hernando Pizarro, De Soto, and the translator got back to camp and reported to Francisco Pizzaro that their diplomatic mission had… not gone great. The oldest Pizarro and his lieutenants then spent a harrowing night trying to figure out what the fuck to do. They thought the Emperor might come to visit them as requested, but more likely he would just attack and kill/capture them all. The Spaniards considered slipping out in the night to head back to the coast for reinforcements and a better opportunity to fight, but they worried they’d be attacked on the retreat, plus it would be cowardly.

Finally, they figured their best shot at fame, glory, and now most importantly, survival, was to bring out the old Cortes playbook and try to capture the Incan Emperor. Maybe Pizarro could negotiate with the Emperor to get access to the capital like Cortes had done. Or maybe the Emperor really would be dumb enough to visit them in Cajamarca and they could launch an ambush.

Granted, while outnumbered by something like 59,832 soldiers, the Spaniards were aware that their odds were not great. But still, they did their best to prepare themselves for battle. At their disposal, the 168 Spaniards had 62 horses, 4 canons, and “fewer than a dozen harquebuses.” They were in a decent defensive position in the city center where they could form chokepoints on narrow roads and use stone houses for cover. But still… they were not super optimistic that their technological and geographic advantages could overcome their 20-40X manpower disadvantage. Many Spaniards assumed they would soon die and spent the night praying to the Christian god.

The entire Incan army left their camp, marched to Cajamarca and then… stopped. It was almost sundown and Incan armies didn’t march or fight at night. Pizarro and the Spanish didn’t know about this tactically suboptimal stratagem, and couldn’t figure out what the Emperor was doing. Setting up for battle? Plotting something? Psyching the Spanish out?

Having no better ideas, Pizarro took a low-risk long-shot tactic by deploying an emissary to reiterate the invitation to the Incan Emperor to visit Pizarro. A Spanish guy ran outside Cajamarca with the translator, yelled the invitation to the Incan army, and then ran back into town to avoid being killed.

Surprisingly, a portion of the Incan army then started marching toward the town center. The Spaniards couldn’t believe that had worked, so they hastened to re-set their ambush by leaving a few men, including Pizarro, out in the open in the town center, while everyone else stuffed themselves and their 62 horses into stone buildings with their few harquebuses and cannons pointed at the ready.

Emperor Atahualpa came into the town center at the head of a 5,000-6,000 man army contingent riding atop a litter carried by some of the most elite nobles of the Empire, the equivalent of princes and dukes. The town center was now extremely crowded, especially since there were only two entrances/exits on the Incan side. According to one Reddit poster, the entire Incan army was unarmed as some sort of show of strength, but MacQuarrie never says anything about this.

The Spaniards knew that a fight in the streets was mostly likely, but they were going to try another low-risk long-shot tactic first. A priest traveling with the Spanish army approached and asked Emperor Atahualpa to join him and Pizarro in one of the nearby stone buildings where the Spaniards planned to immediately grab the Emperor and kill his bodyguards. The Emperor wisely refused, which was expected.

Then it was the priest’s time to shine – he got the chance to read out the “Requirement.” Spanish law mandated that when conquering territory under the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spanish agents were “required” to first make a proclamation to the natives that the Treaty of Tordesillas was a thing and that the natives were now legally Spanish subjects. De Soto had already kind of done this, but I guess that wasn’t official, so the priest did it again, and again it was translated by a teenager who wasn’t that great at the Spanish or Incan languages. Then the priest handed Emperor Atahualpa a prayer book who stared at it in fascination.

Then Emperor Atahualpa stood up and yelled to his men to prepare for battle. The priest ran away and Pizarro yelled for his men to prepare for battle. Then the Battle of Cajamarca kicked off.

The result: In two hours, the Incas suffered 6,000-7,000 dead, along with around 2,000 captured, including Emperor Atahualpa. While many Spaniards were injured, no Spaniards died, only a single black slave.

Spanish-Native Warfare

I am fascinated by the Spanish conquistadors, but most of all, I am fascinated by their warfare.

How is it possible for 168 soldiers to defeat 30,000-80,000 soldiers? This isn’t a myth and this doesn’t seem to be exaggeration, as these numbers are corroborated by dozens of Spaniard and Incan primary and secondary sources.

And it wasn’t just a fluke. There were many battles with similarly lopsided manpower and casualty ratios throughout the conquests, particularly in Mexico where Cortes’s forces were more often harried by native armies. There were rare exceptions when the Spanish lost encounters, but only when ambushed and extremely outnumbered, like La Noche Triste when the Aztec army besieged Cortes within the Mexican capital. But in just about every single open engagement between Spanish and native forces, the Spanish always won and with dramatically fewer casualties despite being absurdly outnumbered.

By my reading, the massive Spanish military advantage can be explained by two primary factors: technology and tactics.

Technology

It might seem obvious that the Spanish leveraged their technology to achieve incredible military victories over the Incas and Aztecs, but I’ve actually seen some pushback against this point. Often, it’s pointed out that the Spanish didn’t have that many pieces of their most advanced technology (guns and cannons), and most of their foot soldiers didn’t have close to full plate armor. On the BadHistory subreddit, there is a highly up voted and often referenced nine-part series on Cortes’s conquest of the Aztecs which argues, among many other things, that Spanish military superiority is highly overrated. And yes, that post is one of the reasons I’m writing this whole essay, because someone is wrong on the internet.

MacQuarrie does a better job of describing how the Spanish trounced the Incas than Bernal Dias does with the Aztecs, and by MacQuarrie’s telling, the single most impactful element of Spanish military technology was cavalry.

The Inca simply could not beat armored soldiers on armored horses in open combat, especially when they charged with lances. The Inca tried many tactics against cavalry, including swarming, barricades, and missile barrages, and nothing worked. They did not have strong enough weaponry to seriously hurt either the horse or rider, and together, the cavalry could literally trample groups of Incan soldiers to death. There are many instances in MacQuarrie’s telling of the Incan conquest in which a few dozen Spanish cavalry charged into Incan armies of tens of thousands of warriors and at least inflicted dozens-to-hundreds of casualties with no losses, or at most, won the entire battle and routed the whole Incan army.

The only standard anti-cavalry tactic that worked every once in a rare while was swarming. Sometimes a horseman would get tired so it couldn’t gallop away, and then it would get overwhelmed by suicidally brave Incan soldiers willing to climb on top of the horse despite the risk of getting stomped or stabbed. These soldiers would then pull the horseman off the horse onto the ground and try to pry his armor off and/or stab him through gaps in his armor. But even when this rare event occasionally occurred, more often than not, other cavalry would come to the rescue of the troubled horseman and drive off the swarm.

Eventually, the Inca did crack cavalry, but only in certain contexts. Incan commanders discovered that horses don’t do well on slopes. On flat ground, cavalry is invincible, but while going up or downhill, they slow down or trip and fall or panic and rear up, or otherwise stop being invincible killing machines, and then they can be swarmed a little more effectively.

Also, though it’s less flashy, we can’t forget that cavalry provided tremendous logistical benefits to the Spaniards. The Incan relay network was amazing relative to the size and scale of the empire, but the Incan Emperor still couldn’t transmit orders and receive messages from underlings faster than the speed of a jogging man. Meanwhile, the Spanish could move significantly faster over shorter and longer distances on horseback, so they could transmit orders faster, mount better raiding and scouting parties, retreat more easily if needed, chase down fleeing soldiers with greater ease, and perform rapid military maneuvers of which the native armies could never dream.

I think the next most important Spaniard military tech was iron, as applied to both armor and weapons. As mentioned, the conquistadors under Cortes and Pizarro were not a unified professional military unit with matching armor sets; they were a rag-tag group of adventurers. The wealthier soldiers, particularly the cavalry, would be decked out in plate armor not too dissimilar from medieval nights, while the poorer soldiers would settle for mostly chain mail and thick cotton with maybe a few plate pieces.

Iron armor, whether plate or mail, was almost always too tough for native weapons. Aztec obsidian weapons were sharp but brittle and often broke on impact with armor. Incan copper-tipped spears probably had a little more penetration but were still outmatched. Even with the motley assortment of Spanish armor, it was apparently sufficient to provide extreme protection to nearly all Spaniards in combat against overwhelming numbers. It’s not like every Spaniard was constantly riposting native attacks with their swords in a duel, rather, the Spaniards were constantly taking melee and ranged hits, but sustaining them without serious injury.

Bernal Dias’s Conquest of New Spain is a great book, but in some ways it’s extremely repetitious. I can’t count how many times Dias says something like, “a horde of natives fired 100 bajillion projectiles at us, and every single one of us to a man received wounds, but no one died.” It’s the same in McQuarrie’s Last Days of the Incas: constant references to projectile barrages that wounded and annoyed but virtually never killed. At one point, MacQuarrie notes that the only way for standard Incan projectiles to kill a Spaniard was if they happen to hit the bottom of a soldier’s face where the helmet ended, and indeed, there is more than one account of Spaniards having their jaws fucked up by sling-thrown rocks, and such a hit even kills one of the Pizarro brothers.

In contrast, Aztec and Incan armor never got above the equivalent level of leather, and usually didn’t cover the entire body. Iron swords, lances, spears, axes, halberds, etc. could easily penetrate anything the natives put up to stop it.

A good example of how a small technological change can act as a huge force multiplier: the Spanish tended to use their melee weapons to stab, the native warriors tended to use their melee weapons to slash. In the combat of the time, stabbing was usually far more advantageous compared to slashing because the former allowed the attacker to keep more distance and therefore stay out of danger, especially against a slashing attack. The reason the Spanish could use more stabbing weapons was because their weapons were made of iron which was far harder than obsidian, wood, rock, or bronze used by the natives. Stabbing weapons made out of those materials broke very easily (with the lesser exception of bronze) whereas iron was strong enough for a stabbing weapon to last.

This one is a little harder to parse for me. Obviously the use of gunpowder represents a tremendous advantage over pre-iron native military forces, but both Cortes and Pizarro did not have many guns in their possession. Both usually had a handful of cannons while Cortes had 40ish infantry guns to Pizarro’s dozenish. But the hand-held guns were harquebuses, which are extremely primitive compared to modern guns, firing maybe 2 shots per minute and very inaccurately at that. In Europe, their greatest use was penetrating any-and-all armor in their path, but that’s not a super useful attribute when fighting against barely-armored natives.

On the other hand, there’s a section in Conquest of New Spain where Dias marvels at single harquebus shots regularly killing entire rows of native warriors. He says that the natives would clump so closely together when bearing down on the tiny Spanish army, and they wore such little armor, that a harquebus shot would go through the first native warrior and just keep on going through a bunch more. So penetration still had its uses.

Then there’s the psychological factor. Emperor Atahualpa’s elite bodyguards freaked out and ran at the cost of their lives because a horse reared up on its hind legs and snorted. I cannot imagine how native warriors reacted to the boom of guns in the early 16th century. The vast majority of fighters had surely never heard anything so loud in their entire lives, and certainly nothing produced by men. Both the Incas and Aztecs understandably initially thought the Spanish were using some sort of magic that produced a noise and then killed enemies, and it wasn’t until they captured the guns that they figured out it was an advanced technology.

Surprisingly, neither MacQuarrie nor Dias say too much about Spanish artillery except for how much of a pain-in-the-ass it was to lug it through Mexican jungles or up Andean peaks. Granted, the Spanish had relatively few cannons, and though more advanced than hand-held guns, they were still fairly primitive in Europe at the time, so there were no Napoleonic artillery maneuvers. But still, Bernal Dias mentions single cannon shots killing 10-15 enemy warriors, so they certainly had their uses.

Tactics

Even people with a passing knowledge of the conquistadors are aware of the key military tech differences: horses, iron, and gunpowder. But less known, and by my reading, far less acknowledged in scholarly sources, is the Spanish tactical superiority. Spanish armies were far better led than native armies both in terms of moment-to-moment leader decision-making, and doctrinal tactical options.

For one, military tactics have evolved over time just as technology has, especially as soldiers have become more specialized. I didn’t read a ton about American native warfare, but it mostly seemed like throwing hordes of soldiers at opponents. The vast majority of the Aztec and Mesoamerican armies consisted of conscripts with little training, and there didn’t seem to be much specialization beyond ranged and melee units. The Incan armies were similar except conquered ethnic groups tended to fight as cohesive units, so there was a little more variety. But I can’t imagine the tactical value of their differentiation compared to the Spaniards’ early form of combined arms warfare that utilized heavy infantry, cavalry, harquebuses, crossbows, and cannons.

For example, even though cavalry charges were the ultimate Spanish weapon, their infantry also performed extraordinarily well against native armies as long as they could hold formation. La Noche Triste was the biggest Spanish disaster in Cortes’s conquest, but it was also a military miracle that Cortes was able to extract about half of his army from the Mexican capital despite being surrounded by an enemy army at least 100X larger. Likewise, Hernando Pizarro managed to hold narrow streets during the Siege of Cusco practically forever. In both cases, heavy Spanish infantry in tight defensive formations were the backbone of the Spanish military effort. No matter how much iron armor a Spaniard soldier had, if he was isolated, he would eventually be killed by native fighters, but when locked in a protective formation, the Spanish infantry could hold their ground and use piercing weapons to pick away at enemy numbers.

A good example of how Spaniard tactics evolved beyond native tactics is the positioning of leaders. European armies gradually did away with the idea of putting their leaders on the frontline, with Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus being the last major commander to famously lead from the front, for which he died in battle in 1632. But both the Aztecs and Incas had a strong tradition of putting their generals not only on the frontlines, but surrounded by colorful uniforms and banners to highlight their presence. This was supposed to be good for troop morale and demonstrate the bravery of commanders.

I guess this worked better during the relatively less deadly clashes between native armies, but it was a disaster against the Spaniards. For instance, after La Noche Triste, when Cortes had lost half of his army in Tenochtitlan, he fled the Mexican capital in a desperate retreat, but the Aztec army caught up and forced a confrontation at the Battle of Otumba. Cortes led 600 exhausted and wounded Spaniards (only 13 of which were cavalry) and 800 equally exhausted and wounded native allied warriors against 10,000-20,000 comparatively fresh Aztec warriors in an open plain. It should have been the end of the Spanish, but Cortes spotted the enemy general on the frontline decked out in feathers and fancy attire, and ordered a cavalry charge against him. The general was immediately killed and virtually the entire Aztec army routed. An extremely similar battle occurred later between the Spaniard and Incan forces at Lima that turned the tide of the entire war.

Note that the Spaniard commanders were also extraordinarily brave and often fought at or near the front, particularly Cortes who fought in a billion small battles. But the Spaniard commanders were rarely at the tip of the spear, and certainly didn’t call attention to themselves. And, to speculate a bit, the Spanish military command structure was more sophisticated, and therefore the loss of a commander in battle would probably have a less catastrophic impact on Spanish military organization and morale.

It’s also worth noting that the Spanish armies were highly tactically superior to the native armies despite the Spaniards being of relatively low professional quality. Again, the Spanish conquistador forces were a haphazard collection of adventurers, most of whom had little-to-no prior military experience. Some had served as mercenaries or fought in Europe, but most were blacksmiths or sailors or whatever that spent their life-savings on weapons and armor for a shot at riches and glory. And yet they were still able to achieve tactical dominance against the armed forces of the Mexican and Incan Empires, including their elite specially trained professional armies (though most rank-and-file native warriors were conscripts).

This is not to say that the native armies were tactically clueless. The Inca commanders in particularly seemed to adapt pretty quickly and try to change up their tactics to fight the Spaniards. But, while there were some successful tactics like using uneven land to fight cavalry or mounting ambushes of small Spanish military units, the commanders always circled back to the same conclusion: they couldn’t beat a massed Spanish army. It didn’t matter what their numbers were. They lost at the Battle of Cajamarca when they had no forewarning of Spanish technology and tactics, but they lost just as badly (arguably worse) at the Siege of Cusco when they had practically infinite reinforcements against a tiny and trapped Spanish army. Whenever the Spanish had sufficient numbers (probably at least 150 soldiers) and competent leadership, native defeat was inevitable.

Completing the Conquest

The Battle of Cajamarca went better than Pizarro could have dreamed. His 167 men defeated an army of maybe 80,000. According to a Spaniard at the battle, “the entire countryside was covered” in dead Incan bodies. Better yet, Emperor Atahualpa was in Spanish custody, and so it was time for the Incas to turn the page to the next part of Cortes’s playbook: using a captured native Emperor to extort an entire country.

Like Cortes, the Spanish (initially) treated the captured native Emperor well. Pizarro and his top lieutenants had a calm sit down with Atahualpa and explained to him through a translator that they would not harm him if he followed their orders. As with Cortes in Tenochtitlan, for the following months, Emperor Atahualpa would basically continue running his empire and even holding court, just always under Spanish lock-and-key and with an implicit (and later explicit) threat of death at any moment.

Pizarro’s first demand was for the Incan army to not try a rescue attempt. Emperor Atahualpa complied and sent out orders to that effect, but there was still a giant Incan army of tens of thousands of men sitting outside Cajamarca, and that made the Spanish nervous.

Pizarro and his lieutenants then discussed how to get rid of this army. Some lieutenants favored using Atahualpa’s authority to chop off the right hand of every Incan soldier. Pizarro overruled this and merely ordered them to disband. Emperor Atahualpa complied. He still had about 100,000 soldiers elsewhere, but the Spanish didn’t know that.

Pizarro’s men then ventured out of Cajamarca to loot the Incan army camp while the Incan soldiers, under orders from Atahualpa, stood by and let it happen. Emperor Atahualpa watched the Spanish soldiers come back to Cajamarca carrying piles of gold and silver booty, including a bunch of the Emperor’s plates and goblets. That’s when Atahualpa got an idea… he could bribe the Spaniards.

MacQuarrie takes a very sympathetic approach to Atahualpa’s strategy here, and IMO, it at least made more sense than whatever Mexican Emperor Montezuma was trying to do with Cortes (infinite appeasement?). Emperor Atahualpa’s previous reports from scouts and now what he was seeing with his own eyes indicated that the Spaniards were obsessed with gold and silver. Atahualpa was a hostage who could be killed at any moment. So it was worth offering the Spanish basically any amount of gold and silver to get himself free, and then these stupid barbarians would hopefully fuck off back to wherever they came from.

So Emperor Atahualpa made a pitch to Pizarro: he would give him “a room full of gold twenty-two feet long by seventeen feet wide, filled to a white line halfway up its height,” which would be set at eight feet tall. Also he would throw in a whole lot of silver. Then the Spanish would let him go.

“Pizarro was clearly amazed by Atahualpa’s offer.” He was so amazed that he didn’t know if it was legitimate. It didn’t seem conceivable that even the Aztecs could cough up that much treasure, so Pizarro thought that maybe the Emperor was just buying time while he came up with a plot to escape. But seeing no better immediate plan, Pizarro agreed to the offer. Meanwhile, Pizarro would fortify his position in Cajamarca and send emissaries back to the coast to request reinforcements from Panama.

The gathering of all this gold and silver was a massive logistical operation that required thousands of human and llama porters. The Spanish sat around with Emperor Atahualpa for six months while the ransom was collected. The Emperor sent out his emissaries with orders to the Incan nobility to empty the royal treasury, forfeit their own treasuries, and empty the government warehouses of any and all treasure they held. After relatively slow inflows during the first few months, Pizarro deployed three of his men to the Incan capital of Cusco with orders from Emperor Atahualpa to oversee the gold/silver extraction operation. These men proceeded to loot royal palaces and the Incan religious equivalent of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome using Incan labor while Incan noble generals sat by helplessly fuming at the injustice.

Throughout this time, the Spaniards and Emperor Atahualpa learned a bit more about each other. The Spaniards were impressed by the Emperor’s authority as he continued holding court, with his noble subjects showing a greater intensity of courtly deference toward him even than Spaniard subjects did toward their King/Holy Roman Emperor. A lot of the Spanish lieutenants, including Francisco Pizarro, took quite a liking to Atahualpa, whom they found dignified and highly intelligent. When away from his subjects, the Emperor relaxed and could even joke around. The Spaniards taught him chess and he played many games when locked away from his subjects at night. In the fifth month, Diego de Almagro, Pizarro’s partner in the entire conquest venture, made it to Cajamarca with 153 soldiers and 50 horses, and for whatever reason, the normally grumpy Almagro soon became particularly close with the Emperor.

Finally, after about six months, the Incan ransom hit the line in the room. Combining the Emperor’s ransom and other assorted plunder, the Spaniards soon fed an estimated 40,000 pounds of gold and silver into a makeshift smelter to be melted down into more easily transportable bars.

It’s difficult to put a value on this sum, but MacQuarrie provides some frame of reference by relating that in the 1530s, the annual salary of a Spanish sailor (which was a pretty dangerous job) was about half a pound of gold (50-60 ducats). Also, a caravel, or standard sailing ship at the time, was valued at about four pounds of gold.

20% of the total sum was automatically reserved for the Spanish king and sent on a long journey to Spain. Counting just Atahualpa’s ransom, this amounted to 2,600 pounds of gold and 5,200 pounds of silver. Pizarro took 630 pounds of gold and 1,260 pounds of silver (worth about $16.1 million today). The rest was divided among Pizarro’s men (but not Almagro’s men) according to rank. Each cavalry soldier received 90 pounds of gold and 180 pounds of silver (about $2.3 million), and each foot soldier received half that amount (about $1.15 million).

Needless to say, Pizarro’s conquest of Peru had already been phenomenally, ridiculously, absurdly successful. Every single soldier who accompanied Pizarro in the first wave was set for life. They earned more from a single battle than they could have ever possibly dreamed, let alone have plundered in a lifetime of ordinary warfare. They were so successful that Pizarro became concerned that a lot of men were going to desert the company despite signing contracts because they didn’t need any more money; Pizarro ameliorated this somewhat by proclaiming that married men over a certain age were allowed to leave with his permission.

For another point of comparison, despite going through far more harrowing warfare and tribulation throughout their multi-year conquest, Cortes’s men in Mexico barely ended up making any money at the fall of Tenochtitlan, mostly because they had repeatedly gained and lost multiple fortunes during successful city sackings and subsequent setbacks. But Pizarro’s men were the equivalent of 16th century millionaires after a few months of work, most of which was spent sitting around camp watching Incas carry gold and silver.

The only problem was that not everyone got a piece of the pie. Almagro and his 150 man contingent had arrived after the Battle of Cajamarca, and though Pizarro and his men were happy to get reinforcements, they brought a lot of tension to the camp. There was an open question on how to divide the treasure; did the reinforcements deserve a cut even though they hadn’t fought? This concern stacked on top of an already increasingly fractured relationship between Pizarro and Almagro, the latter of whom believed that Pizarro had screwed him over before. When Pizarro went to Spain to get permission from the King to conquer the Incan Empire, he had gotten a governorship for himself across the entire territory while Almagro had merely been granted the mayorship of Tumbes (which was currently in ruins). They were ostensibly business partners, but Pizarro had cut him out of access to one of the largest and most valuable resource extraction opportunities in history.

But like Cortes, Pizarro was an excellent diplomat. At Cajamarca, apparently Pizarro did a phenomenal job of not only calming tensions with Almagro, but also getting everything else he wanted. Pizarro convinced Almagro to let the former’s men keep this entire treasure. He promised Almagro that there was far more left to plunder in the Incan Empire, and they would all march on Cusco together to get it. From then on, all the plunder would be divided equally between their men. It speaks to Pizarro’s charisma that the infamously disgruntled Almagro was placated despite never settling the governorship question.

One lingering question remained before the expedition could proceed… what should they do with Emperor Atahualpa?

The Emperor’s cautious optimism early in the negotiations had already fallen into deep depression. He wasn’t an idiot. From conversations with Spaniards, it had become increasingly obvious to him that they were not going to leave Peru once the ransom was paid. Many Spaniards were openly talking about how they were going to divide the Incan Empire into governorships and encomiendas. The arrival of Almagro and his reinforcements indicated that there were many more Spaniards out there and no reason for them not to keep coming.

For yet another fairly obvious signal of his impending doom, Pizarro invited one of the Emperor’s top generals, who was leading one of the three major Incan armies remaining, to visit the Emperor. The guy came and Pizarro simply arrested him. Boom, another major Incan army was destroyed.

The Emperor was correctly worried about keeping his head. His only chance for some sort of reprieve was to convince the Spaniards to keep him alive as a prisoner, so he asked to maintain the status quo and keep him as a puppet-Emperor. Hernando Pizarro, the extremely arrogant brother who first met the Emperor, was particularly friendly with Atahualpa, and when the Emperor heard that Hernando was escorting the Spanish King’s cut of the treasure back to Spain, he asked Hernando to take him as a prisoner to meet the Spanish King and plead his case.

Francisco Pizarro was also broadly sympathetic to Atahualpa from sheer personal contact, but the Emperor had plenty of detractors among Pizarro’s lieutenants. Many suspected that when he held court, he was using the language barrier to secretly transmit orders to underlings to organize an anti-Spanish resistance. And… they were totally right. Atahualpa was doing that. But the suspicious Spaniards couldn’t prove it and Atahualpa denied it.

In the end, the suspicious Spaniards won out. After hesitating for a few weeks, Francisco Pizarro finally decided that Atahualpa had probably worn out his use as a puppet and there was a decent chance he was conspiring, so it was safest just to kill him. Pizarro sent a priest to the Emperor who offered him a chance at salvation. Atahualpa thought that accepting meant he would live, so he did, but it actually just meant he would convert to Christianity and be killed by the marginally less painful method of strangulation rather than the more painful method of being burned at the stake. On July 26, 1533, Emperor Atahualpa was executed at age 31.

The Spanish had a few gloomy days at camp as everyone mourned the Emperor. Francisco Pizarro and Hernando de Soto allegedly both cried and expressed some remorse for not sending him off to Spain in chains. But what was done, was done, and it was time to move on. From among his thousands of other Incan prisoners, Pizarro plucked one of Atahualpa’s brothers, Tupac Hualpa, and declared him the new Emperor of the Incan Empire.

The Spanish march from Cajamarca to Cusco took three months even with the help of native scouts. The walking and riding around some of the tallest mountains in the Western hemisphere was slow and arduous, and the Spanish ran into a bit of trouble. First, the new Emperor died a mere two months into his reign from some Spanish disease. Then, there were suspicions that the captured Incan general was secretly fomenting rebellion, so they burned him at the stake.

On the other hand, some things were going even better for Pizarro than he realized. It turned out that executing Emperor Atahualpa was actually a great strategic move (though sending him to Spain probably would have had the same effect). The Incan Empire had been decapitated and there was no succession process in place since so many nobles had been captured or killed at Cajamarca. The Incan bureaucracy and two giant Incan armies remained, but with Atahualpa, Huascar, Tupac Hualpa, and many of the top Incan nobles dead, there was no one to give any orders. So the Spanish marched relatively unmolested by enemy armies through the heart of the empire. MacQuarrie notes that six Spaniards died on the march, but he doesn’t say how.

Shortly before reaching Cusco, Pizarro’s army was approached by one of the biggest players in the conquest to come: the 17 year old Manco Inca. He was another son of Huayna Capac and half-brother of Atahualpa. But he had been a full-brother of Huascar and had sided against Atahualpa in the civil war. With Huascar’s defeat, Manco Inca had been on the run for months, hiding in the countryside with a small cadre of followers. He didn’t know much about the Spaniards except that they had killed Atahualpa, so he took the initiative to present himself as an ally. The Spaniards shrugged and made him the new puppet-Emperor of the Incan Empire.

Manco Inca proved his value when he immediately warned the Spaniards that the Incan general left commanding the army stationed at Cusco was planning on burning down the capital rather than letting it fall into enemy hands. Pizarro deployed 40 cavalry in advance of his main force to stop the general. MacQuarrie doesn’t give too much detail on the ensuing battle, but apparently these 40 horsemen attacked an army numbered somewhere between 10,000-100,000 and… won. They didn’t just win the initial skirmish, they won the whole battle. The entire Incan army of tens of thousands retreated in the face of 40 cavalry. The Spanish lost three horses in the process (though no men) and killed hundreds of Incan warriors.

That that was it. Cusco was conquered. Pizarro and his army marched into the capital and set up a base of operations. They officially crowned Manco Inca as Emperor with a ceremony, introduced themselves to the Incan nobility, and began working with Manco Inca to form a new army and government. Meanwhile, the rank-and-file Spaniards began a multi-year looting process of Cusco that started with taking whatever gold and silver was left behind in the palaces and temples but soon moved on to going door-to-door in regular homes and ransacking at-will with the explicit legal sanction of the Emperor. It was a good time to be a conquistador.

Four months later, Pizarro conducted his second major treasure distribution, this time with all Spanish soldiers getting a cut, including Almagro’s men. MacQuarrie gives less detail for this one, noting that less gold had been collected than during Atahualpa’s ransom but 4X more silver, and that even Almagro’s men were catapulted to the equivalent of millionaire status.

The conquest was going so well that Pizarro was starting to suffer from success a bit. Everyone was so fucking rich that there wasn’t an incentive to stick around. Why would an ordinary rank-and-file Spanish soldier stay in far-flung Peru surrounded by natives who wanted to kill him when he could retire back to Spain or one of the more developed Spanish colonies and live the rest of his life in luxury? A few of the older, married conquistadors had already left with Pizarro’s permission after the ransom of Emperor Atahualpa, but now the vast majority of conquistadors were ready to hightail it out of there.

Francisco Pizarro wasn’t going anywhere. He was the legal governor of Peru, now known as New Castile, which extended across the entire Incan Empire. His plan was to set up a new subservient native government and tax the locals until he was one of the richest men on earth. But he needed Spanish soldiers with Spanish equipment and training to fill out his new aristocracy to maintain power. To keep his men onboard, he could only offer two prospects:

- As the Governor of New Castille, Pizarro could offer encomiendas, or land grants over which the owner was granted taxation and exploitation rights up to the level of enslaving the native inhabitants. Soldiers granted encomiendas would effectively becoming the dukes and lords of New Castile.

- Despite the mended friendship, Almagro was still pissed off at not having a governorship. So Pizarro agreed to outfit an immediate expedition led by Almagro to modern-day Chile where hopefully there was another big, juicy empire to sack and rule. Any conquistador could join Almagro where they wouldn’t be as useful to Pizarro as the encomienda holders, but would still provide a nearby allied Spanish army for assistance.

In the end, 88 soldiers stayed with Pizarro to become the aristocracy of New Castille despite nearly all being illiterates from the backwaters of Spain, while something like 400-500 men went with Almagro. Unbeknownst to either Almagro or Pizarro at the time, the Spanish King would soon revise his original decision and grant the southern half of New Castile to Almagro as a separate governorship from Pizarro’s Peru. While this would obviously cause problems in the future, at the time, Pizarro was distracted by a completely new external threat.

Ultimate authority over Spanish citizens in the New World technically lay with King Charles V back in Spain, but the de facto control over his people was limited by distance, communication time, the general Wild West frontier nature of the region, and the fluid relationships between crown and subject often mediated by potential gains for both. For instance, throughout much of the conquest of Mexico, Cortes was technically an outlaw by the decree of the King and the Cuban governor, but all was forgiven by the King once Cortes conquered Tenochtitlan and brought home the bacon.

Hence, despite, Pizarro getting a royal license to conquer Peru and an accompanying governorship, shortly after taking Cusco, he faced a Spanish challenger. Pedro de Alvarado was Hernan Cortes’s second-in-command who was instrumental in the Mexican expedition’s success but was overshadowed by his flashier comrade’s prestige and wealth. So Alvarado eventually left Cortes with 550 men to launch his own expeditions, the latest of which was aimed at modern-day Ecuador, which was well within New Castile. It was a blatantly illegal act, but given the fluidity of Spanish authority, Pizarro had serious concerns that Alvarado would sack a chunk of the Incan Empire or even outright fight Pizarro to seize it for himself.

In another sign of the renewed partnership between Pizarro and Almagro, the latter turned his southward marching army around and went back north to re-link with Pizarro’s forces to defend New Castile. But rather than come to blows with Alvarado, Almagro reached out diplomatically and they came to an accord. Pizarro and Almagro bought off Alvarado with one thousand pounds of gold in exchange for 340 of Alvarado’s men joining Pizarro and Almagro’s armies to help hold Peru. Apparently satisfied, Alvarado and the rest of his men fucked off back to Honduras where Alvarado reigned as governor.

With one major opponent out of the way, Pizarro turned his attention to a grander task: subjugating the Incan people. He had already made impressive progress including killing Emperor Atahualpa, killing and capturing a significant chunk of the Incan nobility, extorting a significant portion of the Incan people’s wealth, destroying at least two major Incan armies, and occupying the Incan capital. The next order of business was defeating what remained of the Incan military forces; there were still two major armies floating around commanded by Incan nobles loyal to Atahualpa.

This turned out to be a less serious threat than the Spanish expected. Pizarro dispatched one of his lieutenants to take care of one army and it was chased and beaten until the commander was captured and executed within a few weeks. Better yet, shortly after dealing with Alvarado, Almagro accidentally took out the other major Incan armies. While marching back down south, Almagro’s forces ran into the Incan army, and the Incan generals got into such a fierce argument regarding whether to surrender or fight the Spanish that the head general was killed by his men and the army dissolved. Another Spanish win.

Just when everything seemed in the clear for Pizarro, he was confronted with another Spanish challenger… Almagro.

As Almagro was marching back south after picking up a chunk of Alvarado’s men and accidentally beating an Incan army, he got news from Spain: King Charles V had granted him governorship over the southern half of the Incan Empire. Unbeknownst to Pizarro, Almagro had sent some advocates to Spain to make his case while Pizarro was busy in Cajamarca, and it had seriously paid off.

The now seemingly inevitable clash between Pizarro and Almagro had an additional wrinkle – no one knew exactly where the southern half of the Incan Empire was. The place hadn’t been mapped out, let alone precisely enough to draw a line perfectly through the center of it, so no one knew where Pizarro’s land ended and Almagro’s land began. And it just so happened that Cusco, the capital, was roughly in the center.

So when Almagro returned to Cusco, there was suddenly more tension than ever between not just Almagro and Pizarro, but between their followers. After first seizing Cusco, 88 conquistadors had decided to stay with Pizarro and get encomiendas; now these 88 men, and a certain number of both Spanish and native hangers-on who had arrived since, were dependent upon Pizarro’s status as governor to hold their titles. On the other side, hundreds of Almagro’s men stood to gain encomiendas if Cusco and its surroundings were deemed part of Almagro’s governorship. Within days, members of the two factions were getting into drunken brawls in Cusco’s pubs. Hernando de Soto (an Almagro loyalist) and Juan Pizarro (who obviously supported his older brother) nearly murdered each other in horseback combat.

Part of the problem was that Francisco Pizarro wasn’t even in Cusco anymore. He had been travelling around the northern portion of the Incan Empire trying to set up his puppet regime. When he finally made it back to Cusco after a two month absence, he immediately entered into negotiations with Almagro under the supervision of a newly-arrived royal dignitary. In yet another example of Pizarro’s skilled diplomacy, he made an agreement with Almagro to put the Cusco question on hold while Almagro took all the men he wanted and a massive financial subsidy to relaunch his recently aborted invasion of Chile. The implicit agreement was that if Almagro found a big juicy kingdom to the south, he would get his own conquest and happily set up a prosperous government while Pizarro held Cusco and the north. If Almagro didn’t find a big juicy kingdom to the south, then… well, they’d cross that bridge when they came to it.

In July 1535, almost four years after Pizarro arrived in Peru to start his conquest, Almagro began a southward march with 570 men, leaving Pizarro alone to complete his subjugation of the Incas.

The Importance of Information, Context, and Illusion When Conquering

Francisco Pizarro had shown considerable competence in conquering the Incan Empire, but then he had to hold onto it. This is where he, and his lieutenants, got into trouble.

As a contrast, it’s useful to go back to Hernan Cortes. In my readings of Fifth Sun, Conquest of New Mexico, and Last Days of the Incas, I’ve come away with a tremendous amount of respect for the skills of most of the top conquistadors, but IMO, none stood above Cortes. I think his combination of military, diplomatic, and strategic skills were not only unparalleled among the conquistadors, but should put him in the top tier of general historical conquerors. While Pizarro definitely made some good moves during his early conquest of the Incas, he also had a relatively easy time due to some fortuitous circumstances (like the Incan civil war and recent smallpox epidemic). Cortes threw himself and his army into a more perilous situation, faced more setbacks, and had to personally make more key decisions to finally overcome the Aztecs, and though Cortes made mistakes, on the whole, he performed phenomenally well as an expedition leader.

If I had to refine Cortes to his best characteristic, it would be trickster. It wasn’t just that Cortes was a great liar, it was that he had an insane mastery of understanding the relevant information in any given context, and then using well-placed lies to manipulate both enemies and allies into positions that most benefited himself. The conquest of Mexico was not just a series of battles, it was a series of interpersonal, diplomatic, and geopolitical deceptions orchestrated by Cortes.

For instance, early in Conquest of New Spain, Cortes established a settlement on the coast and started making his way inland in the vague direction of Tenochtitlan, the Mexican capital. Here is a sequence of events that followed:

Cortes Solves A Morale Problem.

About half of Cortes’ men were loyal to the Governor of Cuba rather than Cortes. A lot of those men and many of Cortes’ loyalists were exhausted and worried about the risks of continuing the expedition. So Cortes came up with the idea to scuttle (run aground) his ships, thereby making a full retreat an annoying and time-consuming maneuver. But Cortes worried that he would come on too strong if he outright suggested this, so according to Bernal Dias, Cortes subtly dropped hints of this policy to some loyalists, they spread it around camp, and then some moderate loyalists brought the idea to Cortes. He pretended to think it over for a while, then made a big charismatic speech to the army endorsing it, and then proposed it to his men all at once and they assented with a big cheer.

Cortes Stops (Completely Justified) Deserters

Everyone was on board with the ship scuttling plan except for a portion of the Cuban Governor loyalists. They ask Cortes to leave with the ships and they reminded Cortes that weeks earlier he had made an explicit arrangement with the entire expedition that anyone could leave any time they wanted with full supplies. Cortes couldn’t spare the manpower nor supplies, so he came up with a plan where he made a big public show of shaming the Cuban Governor loyalists while giving them their cut of the plunder and supplies. This aligned the Cortes loyalists against these guys, and there was such a hostile atmosphere in camp that the Cuban Governor loyalists backed down and agreed to stay.

Cortes Mounts a Booty Kick-Up Ruse

Cortes’s army had gotten less plunder than it expected thus far, and Cortes still had to send his legally mandated 20% of the plunder to the Spanish King. However, a lot of his men had low morale and didn’t want to give up their meager shares. But Cortes knew that if he sent back too little treasure to the King, it would cause him political problems. He was stuck between two forces with limited resources to deploy between them.