Over the summer, I spent about two weeks in Tajikistan, mostly in Dushanbe (the capital) and various points along the Pamir Highway, which borders Afghanistan and later leads into Kyrgyzstan.

This was my first time in central Asia and easily one of my most interesting trips in a while. Tajikistan is a fascinating mixture of Soviet, Islamic, Persian, steppe, and Himalayan culture, all rolled into one beautiful, weird, dysfunctional country, and I couldn’t get enough of it. So this essay will be similar to Notes on Mauritania and Notes on Guinea with more of a focus on my day-to-day travel than the history.

Overview

Population (2022) – 9.6 million

Population growth rate (2022) – 2.1%

Size – 55,251 square miles (a little bigger than Greece or New York)

GDP (nominal, 2022) – $10.5 billion

GDP growth rate (2022) – 8%

GDP per capita (nominal, 2022) – $1,050

GDP per capita (PPP, 2024) – $5,800

Inflation rate (2018-2023) – 3.8%-9%

Biggest export – Gold

Median age – 22

Life expectancy (2021) – 72

Founded (independence) – 1991

Religion (2020) – 96% Muslim (virtually all Sunni), 2% Christian (mostly Russian Orthodox)

Corruption Perceptions Index – Rank #162 (out of 180)

Heritage Index of Economic Freedom – Rank #137

The Stans

Ignorant people (like myself two months ago) tend to lump all the Stan countries together because they seemingly exist in a blank impossible-to-remember nebula on maps. So here’s a quick overview of the Stans – minus Pakistan and Afghanistan because everyone knows about them and thinks of them separately – to give a reference point for Tajikistan:

Kazakhstan:

- Shaped like a large amorphous oval blob

- The wealthiest of the bunch, lots of oil and gas (low-tier petrol state)

- The most ethnically and culturally Russian but the natives are ethnically Turkic

- Got independence from the USSR in 1991 and was run by the pre-independence Soviet leader until 2019 as a quasi-dictatorship (even now he retains power from the shadows)

- Geography is mostly steppe (grassland plains), was once described to me by a person who had biked through 90% of the world as the most geographically boring country on earth

- The government and locals don’t like when you bring up Borat

Uzbekistan:

- Shaped like a fucked up parallelogram with sideways Italy sticking out of it

- Second wealthiest of the bunch but far poorer than Kazakhstan, lots of natural gas to the point where most of their cars run on it

- Culturally/linguistically Turkic

- Got independence from the USSR in 1991 and was run by the (particularly brutal) pre-independence Soviet leader until 2016 as a quasi-dictatorship, has since economically opened up to the world and is doing pretty well

- Lots of desert in the west, lots of mountains in the east, has most of the now-dead Aral Sea

- Claims to be the successor state of the empire of Timur the Lame

Kyrgyzstan:

- Shaped like a squid

- Third wealthiest of the bunch (ie. quite poor)

- Culturally/linguistically Turkic

- Got independence from the USSR in 1991 and was run by the pre-independence Soviet leader until 2010 as a quasi-dictatorship, has been a very unstable oligarchic democracy ever since

- Geographically looks shockingly similar to Switzerland, basically all mountains and valleys, competes with Tajikistan to be the prettiest of the Stans in terms of natural scenery

Turkmenistan:

- Shaped like a bent and somewhat rounded rectangle

- Technically the second wealthiest of the bunch due to huge natural gas exports but no one counts Turkmenistan because it’s almost completely cut off from the rest of the world politically, economically, and socially

- Culturally/linguistically Turkic

- Got independence from the USSR in 1991 and was run by the pre-independence Soviet leader with a difficult-to-pronounce name (Saparmurat Niyazov) until 2006, then another leader with an unpronounceable name (Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow) took over until 2022, and his son with an unpronounceable name (Serdar Berdimuhamedow) has ruled ever since

- All three post-independence rulers were Kim Jong Un-style crazy cult of personality purveyors which lent Turkmenistan the nickname “the North Korea of Central Asia“

- Full of weird laws like a ban on lip-synching and traditional clothing mandates and outlawing the circus

- Would love to go to it but getting a visa is supposed to be difficult and I didn’t have time

Tajikistan:

- Shaped like nonsense

- Poorest and least economically developed, much of the countryside doesn’t even have electricity

- Meager economic production from gold and coal and aluminum, most of which is mined by the Chinese for a cut of the profits

- Culturally/linguistically Persian, the Tajik language is a derivation of Farsi

- Got independence from the USSR in 1991 and had some power struggles until a Soviet guy took over in 1994 and then won a brutal civil war against a coalition of Islamic extremists and has been running the country ever since

- Geography is almost all mountains (50% of the land is above 9,800 feet)

Wealth

The per capita GDP of Tajikistan lists between $1,050 and $1,200, putting it around the bottom 30 or 40 poorest countries on earth. Going off World Bank numbers, Tajikistan is in the same per capita wealth league as Ethiopia, Sudan, Myanmar, Rwanda, and Uganda, and its wealth level is about half as much as that of Mauritania, Ghana, Kenya, Cambodia, and Nicaragua.

I was aware of these figures when I stepped off the plane and was quite surprised by what I saw in Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital. After leaving a very Soviet airport, I was driven through downtown Dushanbe, which looks like this:

Sure, this is the dead center of the capital so you’d expect it to be significantly wealthier than the rest of the country, but still, the scale of development in Dushanbe is striking for a $1,000-$1,200 GDP per capita nation. With the arguable exception of Nairobi in Kenya, the capitals of even the nations with 2X GDP per capitas don’t compare to Dushanbe. Here’s Nairobi:

Here’s Accra in Ghana:

Here’s Phnom Penh in Cambodia:

Here’s Nouakchott in Mauritania:

Here’s Managua in Nicaragua:

Once you get outside Dushanbe, especially into the more rural areas, it really does look like mid-to-lower-tier African poverty and the numbers start to make more sense. Here are a few random villages:

These villages only had electricity for about four-to-six hours per day, had limited running water, no sewage, and used coal stoves for heat. Virtually all local economic activity is based on livestock, but often more money comes in through remittances from migrant workers in Russia or Europe. In 2014, Tajikistan was the most-remittance based economy on earth, amounting to almost half of its GDP. The countryside is dotted with half-finished concrete homes which I was told were the long-term retirement plans of Tajiks working abroad; they build their structures for a few months each year over many years or decades using trickles of funds earned from abroad. When the structures are finished, they prepare them to be their permanent homes once they retire from migrant work.

Aside from the usual developing country trend of concentrating wealth in the capital due to corruption and asset hoarding, what explains the discrepancy between the apparent affluence of Dushanbe and the blatant poverty of the rest of the country?

As someone who has traveled through a lot of developing nations over the last few years, the by-now boring and repetitious answer is… China. A local expert described Tajikistan to me as a “Chinese colony.”

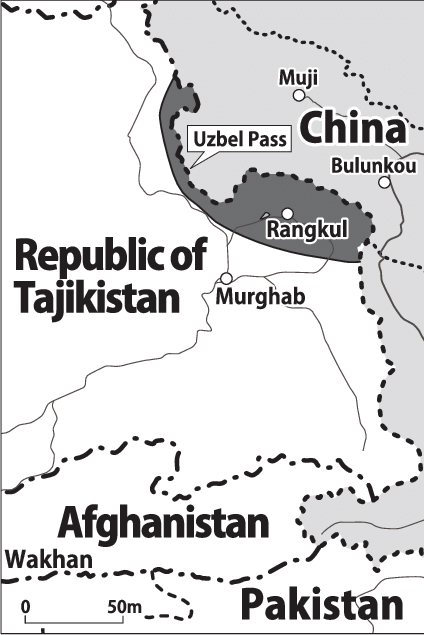

Unlike the oil and gas-rich Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, China and Tajikistan’s partnership started over geopolitics rather than economics. In 2011, Tajikistan ceded 386 square miles to China, pretty much all of which was desolate, unpopulated Himalayan mountains. In return, China agreed to give up its demands for 11,000 square miles of Tajikistani land that dates back to an 1884 claim made by the Qing Dynasty.

But China has more pressing geopolitical concerns regarding Tajikistan. To Tajikistan’s east lies the Chinese region of Xinjiang, which is dominated by Muslim Uyghurs who have historically revolted against the communist government and are still in the midst of an awful reeducation campaign; to the nation’s south lies Taliban-controlled Afghanistan; and within Tajikistan there was a brutal civil war in the 1990s which nearly resulted in radical Islamic factions taking over the government. So for all its weirdness and faults, China sees the current secular authoritarian quasi-dynastic regime of Tajikistan as a bulwark against Islamic chaos on one of its most vulnerable borders.

Thus China has been seemingly quite generous with Tajikistan despite the lack of significant economic output throughout most of its modern history. The aid/grant/loan money began to trickle into Tajikistan after the settlement of the border question in the early 2010s. In 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative was formally adopted, and Tajikistan was swept up along with the rest of Central Asia, with China becoming by far the country’s largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2016, China installed a military base in eastern Tajikistan. In 2021, China established special military units (allegedly only consisting of Tajiks) that seem to be tasked with rapidly putting down potential Islamic rebellions in the remote Pamir region. Also in 2021, Chinese investment reached $211 million, or 62% of FDI. In 2023, China built a “super observation station” in Tajikistan, allegedly to monitor extreme weather patterns and climate change trends.

By 2022, China held $2 billion in Tajikistani debt, more than half its total debt at the time. What has Tajikistan been doing with all this borrowed money?

In the early 2010s, the Tajik government spent more than $210 million (more than 1/10th of its annual budget) on developing Dushanbe, but the vast majority of this funding went toward big government palaces and monuments (more on that later). I can’t find good data on recent agreements between Tajikistan and China, but my speculation is that there has been a dramatic ramp-up in funding for the former over the last few years. According to all the locals I spoke with, Dushanbe has undergone a seismic transformation recently; all of those high rises sprang up in the last two or three years. Virtually all of old downtown Dushanbe, which consisted of two-to-three story buildings, was demolished.

I’ve traveled through inland China, and new Dushanbe looks exactly like any one of those dozens of random Chinese cities that no one has heard of but which have 5+ million people and have undergone rapid development over the last decade. I’d bet serious money that Dushanbe’s new structures are based on Chinese plans and were mostly or entirely built by Chinese workers and money.

The catalyst for this new funding is likely recent mining developments. The Tajik economy as a whole has had impressive growth over the last decade, rising from a GDP of $7 billion in 2016 to about $11 billion in 2023, mostly due to mining but also an increase in remittances prior to the Ukraine War. With some Chinese investment, Tajikistan fortuitously discovered significant gold deposits in 2011. Since then, production has steadily ramped up from 2,400 kg annually to almost 12,000 kg in 2022, which, while significant for humble Tajikistan, still leaves production at less than one third of Argentina, the 20th largest gold producer in the world. From its Soviet days, Tajikistan also has one of the largest aluminum production facilities on earth (which consumes 40% of Tajikistan’s electricity).

So my guess is that sometime in the last five years, China was granted some big mining concessions in exchange for development and infrastructure funds. My understanding is that the rest of the Stans also deal with China, but far more cautiously, and retain closer economic ties with Russia, though these relations have frayed to various degrees since the start of the Ukraine War.

(Note – like Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan was largely relegated to cotton production by the USSR despite cotton being extremely water-intensive and the region having very little water [thus leading to the death of the Aral Sea]. Cotton is still a fairly significant portion of the Tajik economy, but its proportional value has been waning, and in 2023, the cotton industry was a net-loss for the country.)

Dushanbe

Dushanbe doesn’t get a lot of love from travellers but I appreciate Tajikistan’s capital. It’s a weird little city with its own quirks and is very much worth walking around for a few days.

Most capitals of developing countries tend to have way too much sprawl and traffic as old cities try to keep up with rapid development and population growth fueled by urbanization and capital inflows, leading to filthy urban nightmares like Lagos or Conakry. Dushanbe has closer to the opposite problem where a fairly quaint city with a modest population is undergoing rapid top-down development but the economy and population are not keeping up.

The city only has a population of only about 1 million in a country of less than 10 million (the second largest city is only around 180,000). Kazakhstan’s Astana and Uzbekistan’s Tashkent also underwent rapid development recently, but both countries have far higher populations and have received some immigration from their neighbors. Meanwhile, Tajikistan has a sizeable net-emigration, and its few considerable wealth sources (basically just government-run mining companies) aren’t labor intensive enough to attract many Tajiks to the capital.

As a result, Dushanbe feels depopulated. The four-to-six-lane avenues running throughout the city in grids have almost no traffic. The brand new high-rises emanating from the city center have lots of luxury brands in their floor-level storefronts (mostly Russian and Chinese companies I think), but the middle and especially upper floors are almost all empty. There are a few moderately bustling street corners downtown and a few more when you get into the outskirts of the city where buildings rarely pass two-stories, but as a whole, Dushanbe is calm and quiet.

Which goes well with its tidiness. The sidewalks are invariably clean with almost no litter in sight until you get to the outskirts. The downtown high rises are impeccably maintained, and some peeling paint aside, even the old Soviet buildings still look good. The ample public parks are well-trimmed and a small army of landscapers patrol them for imperfections. Even the cars driving throughout Dushanbe seem oddly clean.

This is all by design. I’m not sure if it’s done for the sake of tourism or international prestige or vanity, but Dushanbe has a set of draconian tidiness laws. Anti-litter laws are strictly enforced with harsh fines. Cigarettes can only be smoked in special zones outdoors. Loud music is prohibited after 10 PM. Cars are legally required to be dirtless and mudless, which isn’t too difficult to maintain within Dushanbe, but right outside the city, the roads get dusty and filled with potholes, so a cottage industry of car washers have emerged on every road leading into the city to protect inhabitants from dirty car fines (and often bribes) eagerly handed down by the police.

The landmarks of Dushanbe lean a bit tin-pot dictatorish. Autocrats infamously love to try to outdo each other by building tall skyscrapers, but Tajikistan can’t afford to shell out billions of dollars on vanity projects, so it set its sights on humbler targets. Hence Dushanbe hosts what was once the largest flagpole in the world, constructed with a mere $3.5 million. It is 165 meters high, which I know not through Wikipedia, but because four separate Tajiks proudly quoted the figure to me without prompting.

Sadly, the Dushanbe flagpole lost its status as the world’s tallest in 2014, only three years after its construction, to the Jeddah Flagpole in Saudi Arabia, which I have already seen without knowing its illustrious status in the world flagpole standings:

I have to admit that I find it kind of funny that Tajikistan spent $3.5 million to win an extremely petty international prestige project contest, and then it lost a few years later to a country with 30X the GDP per capita and 100X the GDP. Saudi Arabia’s lead lasted for seven years until Egypt took the top spot and Russia slid into second place. But the ultimate winner in this ongoing affair is Trident Support, a San Diego-based company that has been making a killing building a lot of the largest flagpoles in the world.

A more interesting Dushanbe landmark is the Independence Monument, which looks like… I don’t know. My best description to a blind man would be “a Central Asian scepter sticking 150 meters out of the ground.”

The cool thing about the Independence Monument is that no one goes there. I went in the middle of the day on a Tuesday and I was the only visitor. Inside is a multi-floor museum with Tajik art (both old and modern), a bunch of gift shops, some maps, and fifty portraits of the president (more on that later).

Throughout my entire 30 minute visit, I was basically stalked by a security guard. At first I thought he was just doing generic patrols while I wandered around, but he always stayed about 20-30 feet away from me while I meandered. Then, whenever I got to an elevator (I had to take three separate ones), he would walk up beside me, press the buttons, and make sure I got to the next floor, at which point he would resume his 20-30 foot distance shadowing. He never spoke to me until I got to the very top where there’s an excellent view of all Dushanbe. Then he said a few broken words to me in English for five minutes which concluded with asking me how much a visa to the US costs.

From the Independence Monument vantage point, there’s a good view of the heavily White House-inspired president’s home, known as the Palace of the Nation:

Some fun trivia from Wikipedia:

“In early 2006, the Dushanbe Synagogue and the local mikveh (ritual bath), kosher butcher, as well as Jewish schools were demolished by the government without compensation to make room for the new palace. After an international outcry, the government announced a reversal and said that would allow the synagogue to be rebuilt at its current site. However, in the final stages of the palace’s construction, the government destroyed the entire synagogue, leaving Tajikistan without a synagogue as it was the only one in the country (this resulted in the majority of Tajik Bukharan Jews having negative views of the Tajik government).”

Another major Dushanbe landmark is the Tajikistan National Museum, which is impressive in scale (15,000 square meters of display halls) and design. Though, like the Independence Monument, it was nearly deserted when I visited. I saw maybe a dozen Russian tourists milling about, but otherwise it was just me and the 50 babushkas stationed throughout the museum making sure I didn’t steal any pottery shards.

One highlight was the modern history section which omits the Tajikistan Civil War that lasted five years in the 1990s and left up to 200,000 dead. The sole mention of the entire affair is on this plaque:

The other highlight is a room that displays all the diplomatic gifts given to Tajikistan over the years. This includes a cool Soviet machine gun from Putin, a copy of a letter by Muhammad from Iran, and a mace from Saudi Arabia.

Here is Dushanbe’s (Tajikistan’s?) only Western fast food restaurant, a KFC that opened in 2021. I was told by a local that it was pretty big deal when it arrived and is still a favorite spot for young Tajiks.

In the process of remodeling the city, the government has been shutting down a lot of the tradition bazaars. One big market remains and it looks really cool:

A final interesting landmark is the Dushanbe-2 power station, a coal plant that supplies much of the city’s energy. I like the colors, it’s a nice touch:

The People

If I had a nickel for every time a man from a third world country told me about his marital infidelity with no prompting, I’d have… maybe 30-40 cents.

My latest nickel came from a talkative Tajikistani entrepreneur who spends half of every year in Moscow for business, but also to sleep around with his many mistresses. He claimed to have been faithful to his wife until he was seduced by a beautiful Russian woman who may or may not be related to a prominent Russian oligarch, and then that unleashed a flood of infidelity which he couldn’t stop now even if he wanted to. He was quite eager to take me and an Australian in my hostel out clubbing, and I got the sense that even the current proximity of his wife would not be a hindrance.

Of course, I am not going to write off the marital loyalties of an entire country based on a single testimony, especially since I have counter-testimony. I spent an enjoyable evening at a bar with an early 30-something Tajik guy who had lived in the US for the last 10 years (mostly as an Uber driver) and spent three months per year back in Dushanbe. Somehow marital infidelity came up with him, and though he wasn’t married, he was quite emphatic that it was very rare in Tajikistan, in part because men like him were openly paranoid about their wives and imposed a sort of Pence Rule on all the other men, both within and outside their social circles.

We talked at length about the US and Tajikistan and he explained that though he loved his homeland, he was quite happy living in the US where he could make a far better living. I inferred that his family was middle class or even upper-middle class by Tajik standards given that they had managed to get him to the US and owned multiple properties in Dushanbe (which were presently rapidly appreciating in value), but they weren’t politically connected and therefore couldn’t get rich at home. He confirmed that his Uber driving was pulling a lot of the family weight to take care of his now-retired parents.

The other big weight-puller was his older brother, the eldest of five siblings. This brother didn’t make much money (as some sort of police informant if I understand correctly) but he lived at home with his parents and would never move out until the parents died. My bar companion explained that this was not only a normal arrangement for an eldest Tajik son but an explicit duty for all elder sons in Tajikistan. I pointed out that such a requirement sounds extraordinarily restrictive and even repressive for first-borns, but my companion dismissed this notion (probably as American selfishness and atomism) and opined on the moral value of taking care of one’s parents. He was a stark believer in this aspect of Tajik culture and tradition.

I asked what would happen if a first-born son refused this duty. He said it would probably result in him being disgraced and disowned. I asked how his parents were ok with him moving to the other side of the world while his brother stayed home forever, and he said that having a child move to the US was too good of an opportunity for any Tajik family to pass up.

I asked my companion about Tajik government corruption. He said the military was uncorrupt and shouldn’t be fucked with, but the cops were generally assholes and will ask for bribes during many encounters. And of course, the President and his entire family are extremely corrupt and control the entire economy illicitly, but he still maintained a positive opinion of the political leadership because they didn’t take too much and recently the economy was booming so they seemed to be doing a good job. Plus, he said there was a major lower-level corruption crackdown over the last few years, and police harassment of businesses, both big and small, had been virtually eradicated, which was great for the economy and the common man, so the President and his cronies seemed to have their priorities straight.

I asked if I should be worried about the cops, and I was assured that I should be less worried than anyone else. Allegedly, for years the orders from the top have been to never fuck with foreigners in Tajikistan. The President is evidently very concerned with Tajikistan’s appearance to the outside world, hence the draconian cleanliness laws in Dushanbe and rampant construction, and hence foreigners are never to be extorted by greedy cops. I, appearing Russian to locals, would be considered a foreigner on sight.

I asked about the criminal justice system and I was told there wasn’t much of a formal one. My companion explained that most matters were handled internally by families. For instance, if a 20-something got in a fight with another 20-something and the cops got involved, the police would most likely contact the families and let the parents and brothers sort that shit out with a warning not to cause trouble again. The families would enforce order through shaming, threats of social ostracization, and possibly physical violence.

(On this particular point and some others, I wondered whether my companion had an overly rosy and maybe sanitized view of Tajik culture, which isn’t uncommon for immigrants to have toward their homeland.)

Both the guy cheating on his wife and my drinking companion were extremely friendly. Both went above and beyond in reaching out to me, offering me a place to stay, advice on where to go and what to see, connections to other people, and both wanted to hang out with me as much as possible. I got the sense that they both loved the idea of an American seeing their rarely visited and internationally neglected homeland.

I also got that sense extremely strongly from a bunch of other locals even when they spoke little-to-no-English. Most of the time, I got little attention on the streets of Dushanbe because everyone assumed I was a random Russian (tourist or Tajikistan inhabitant), but as soon as I opened my mouth to say “niet Ruski,” I became an instant micro-celebrity. They would deduce that I only spoke English, then ask where I was from, and my answer of “America” was invariably met with smiles and wide eyes and usually a handshake.

In one instance, I was in a fort museum in the countryside accompanied by three Europeans. Two tour guides asked in very broken English where we were from. The first European answered and the guides politely smiled and nodded. The second European answered and the guides politely smiled and nodded. The third European answered and the guides politely smiled and nodded. I answered and the guides said “American!” and got giant smiles on their faces and their eyes blew up and they shook my hand and they asked me a bunch of questions, and then one of them yelled across the museum to get the attention of this high school kid who was studying English and he spent the rest of the museum visit following me around and asking me questions excitedly. At the end, after they had all shaken my hand again and said goodbyes in broken English eight times, I had to apologize to the Europeans for their misfortune of coming from inferior countries that didn’t warrant such adoration.

(I am kidding of course. I spent nine days with the three Europeans and not only were they all delightful, but they got ample revenge on me by chronically spouting anti-American sentiment in a 3-on-1 gang-up. In my experience as a traveller, I have heard more unironic anti-American talk in Western Europe than anywhere else on earth.)

I wish I had talked to more Tajiks, but aside from the guy who was cheating on his wife, my drinking companion and two of his friends, and my driver on the Pamir Highway, it was difficult to find any locals that spoke English, even at a cursory level. I’m told that younger Tajiks can speak it pretty well, but I didn’t have many interactions with them.

One final note on the locals – due to an apparent combination of local fashion sensibilities and I guess fabulous Persian hair, a lot of Tajik men have a hair style that I can only describe as “Beatles.” And it’s not just the younger men either; older guys and even men who definitely work in the government have this groovy hairstyle.

Religion

Tajikistan’s population is almost entirely Muslim, as is its long-time president and entire government. And yet, it is not considered a very tolerant state for Muslims. From a 2023 US government report:

“As part of an effort to maintain complete, authoritarian control over all segments of society, the government of Tajikistan commits systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations of religious freedom. The Tajik government has placed undue restrictions on all facets of religious practice, including prayer, celebrations, education, and rituals. Those who fail to comply with Tajikistan’s regulations can face severe penalties. While Tajikistan’s religious freedom violations negatively impact all religious groups, they especially target the Hanafi Sunni Muslim majority.”

Christianity is primarily based around the teachings of a pacifist hippy who famously preached a spiritual separation of church and state with, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” In contrast, Islam is based on the teachings of a head-of-state (ie. warlord) whose words and actions were said to be the infallible projections of god. Hence, Islam as a doctrinal belief system has a lot more to say about the workings of government than Christianity or the vast majority of religions. This has resulted in an unusually intense intertwining of state and religion throughout most of the Islamic world.

There have been exceptions: most notably the modern Turks and the Baathists in the Middle East who led the secular regimes of Iraq, Egypt, and (still) Syria. Central Asia is another exception grouping. The Islamic elements of the Stans were kept under low key suppression by the Soviet Union for 80 years, partially due to the general atheism of the USSR, and partially because local Islamic elements attempted an unsuccessful widespread revolt in Central Asia against Czarist Russia and then the USSR in the 1910s and 1920s known as the Basmachi movement.

(Random factoid – the Ottoman Empire entered World War I under the direction of the Young Turks, a group of nationalist liberal-ish modernizers led by a triumvirate of co-dictators, one of whom was Enver Pasha. At the end of WWI, Enver fled the country and ended up in Soviet Moscow where he somehow finagled his way into a military command to suppress the Basmachi movement in Central Asia. But he quickly betrayed the USSR, joined the Basmachis, and led guerrilla fighting against the Soviets until he was machine gunned to death in 1922 near Dushanbe.)

When the USSR fell, each Stan got independence under their local Soviet leadership. Without the protective umbrella of Moscow, each government had to figure out how to maintain its secular authoritarian states over more religious Islamic populations. All embraced anti-Islamic suppression to varying degrees (most harshly in Uzbekistan) while proclaiming marginal adherence to the faith to placate the masses. Despite some terrorist movements and a few terrorist attacks, the former Soviet Stan governments have largely evaded serious domestic Islamic resistance to their rules.

That is, with the exception of Tajikistan. After independence, the local Soviet leadership couldn’t get its shit together (more on that later) and the country fell into a civil war from 1992 to 1997. The details of the war are rather sparse online, but the rough high-level conflict consisted of the authoritarian secular government holding onto the Soviet state apparatus in a few cities while various Islamic groups seized the vast, mountainous, sparsely populated countryside. Numerous attempts were made to take the cities and some almost succeeded, but they could never quite pull it off. The rebels were supported by Iran, Al Qaeda, and other Islamic terrorist groups in central Asia, while the government held on for dear life with support from Russia, Belarus, and the other Stan governments. The listed death toll wildly varies from 20,000 to 200,000, but there’s more agreement on about 10% of the population being displaced and the already meager Tajik economy being wrecked.

In 1997, the United Nations brokered a peace deal that left the government in power but promised the opposition 30% of the legislature. The government signed the deal and then slowly reneged until the last prominent opposition leaders were rounded up and arrested in 2015. Since then, the government has maintained its Soviet-style secular authoritarianism with relative stability and overt-but-not-extreme suppression of Islam within its borders.

For instance, the government shut down 1,500 mosques in 2011. Since around that time, the government has required special permits to build new mosques and for individuals to join Islamic organizations, and existing groups are closely monitored by the “Committee on Religion, Regulation of Traditions, Celebrations, and Ceremonies.” At least back in 2011, mosque sermons were limited to 15 minutes.

There are legal restrictions on Islamic education, with particular limits on getting foreign religious education, and the publishing of Islamic writing. Salafism, an extremely conservative form of Sunni Islam, is outright banned. Arabic names are banned and cousin marriage (which is traditionally sanctioned in Islam) is banned. And if I’m reading the US report correctly, it seems to be illegal in Tajikistan for parents to allow their children to be involved in Islam at all unless they get a special permit from the government.

One of the few things Tajikistan is slightly known for internationally is its ban on long beards, which started in the mid-2010s, and depending on the source, is either an official law or an informal decree from the president that is nonetheless enforced by the police. I won’t claim to understand the specifics, but long beards are associated with conservative Islam while being clean shaven is associated with good old fashioned Soviet secularism. Supposedly, the Tajik government has arrested hundreds of thousands of men for beard violations and forcefully shaved at least 13,000 men in 2016 in a single region. Beard permits are available for actors and other men who have good secular reasons for needing hair on their faces.

When I talked to a few (very secular) locals at a bar about the beard ban, they told me that (even if I wasn’t currently clean shaven) I had nothing to worry about. The police would assume I was a Russian and wouldn’t mess with me anyway, but even if I grew out a beard, I don’t look Islamic enough. It so happened that one of these Tajiks at the bar actually did have a bit of a beard, so I asked if it was illegal, and he said it probably was, but that he wasn’t concerned because he also gave off un-Islamic vibes with his motorcycle, leather jacket, and because he was on his fourth beer of the night.

So maybe the beard ban isn’t heavily enforced anymore. Regardless, I did get the strong sense that religion is not a big deal in Tajikistan, or at least it isn’t openly and enthusiastically practiced compared to the dozens of Islamic countries I have visited in the Middle East, West Africa, and Southeast Asia. I literally never saw a Tajik in prayer. I never once heard the Islamic call to prayer from mosques (I’m not even sure if it’s legal). I barely saw any mosques besides the Central Mosque in Dushanbe, which is was the largest in Central Asia and was largely funded by Qatar (I guess the president’s desire for prestige projects outweighs his secularism).

Bars and liquor stores are common in Dushanbe, though alcohol seems almost non-existent in the countryside. Likewise, in Dushanbe I’d estimate that 50% of the women wore hijabs (head scarves that don’t cover the face nor the rest of the body) while in the countryside, it was more like 90%. However, I didn’t see any niqabs or burkas except for a few women walking around with their clearly Arab husbands. Many young women in Dushanbe dressed in a typically Western manner with jeans, albeit with no cleavage nor shorts.

(EDIT – A few days before I published this, the Tajikistan government outlawed the hijab.)

The US report also notes that though the government mostly targets its fellow Sunni Muslims, it also applies broad religious suppression across the board. For instance, Jehovah’s Witnesses are outlawed and “face intense harassment from authorities, including home raids, fines, surveillance, and brief detainments.” Other Christian groups, like missionary-oriented Baptists, face an uphill battle getting permits to build their churches and proselytize. However, the Russian Orthodox Church “does not experience much official repression, in large part because Orthodox Christians do not proselytize and because of the church’s connections to Russia.”

Fearless Leader

I asked a taxi driver with surprisingly good English, “is the President good”?

His verbatim response: “of course, how else could he rule for 32 years?”

One of the perks of ruling for 32 years is amassing the political capital to put pictures of yourself everywhere:

Personally, I think the President looks like a lost Leonid Brezhnev clone:

Emomali Rahmon has indeed been the president of Tajikistan since 1994, and although he wasn’t the leader of the pre-independence Soviet state, like the first presidents of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, he is undoubtedly one of those guys in spirit.

Rahmon (originally Rakhmonov until he changed his last name in 2007 to sound less Russian) was born in 1952 in a rural region of the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which consisted of almost nothing but rural regions. His father was a decorated WW2 veteran and his uncle died in the military in the late 1950s while doing god knows what in Ukraine.

Say what you want about the USSR, but it apparently allowed individuals to rise from obscurity to great power. From his humble origins, Rahmon got a decent education in economics at the Tajik State University, then “worked as an electrician at a butter factory in Kurgan-Tube,” then overcame living in one of the most land-locked places on earth to join the Soviet Navy to be stationed in sunny Primorsky Krai (which is north of North Korea), then went back to being an electrician, and then a salesman, and then he started his surprisingly successful political climb by getting involved in local Tajik union leadership. Eventually he became the head of the collective farms in his home region.

Based on his long list of political titles, Rahmon seemed to have popped into the national leadership of the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic right when it was getting independence. In 1990, he was one of many “people’s deputies,” which was a legislative role, and being in his 30s, Rahmon had to have been on the younger side of the local Soviet apparatchiks.

When the USSR fell in 1991, the pre-independence leaders of all the other Stans rapidly consolidated their power under a new government with the right carrots and sticks to keep the other top party leaders in line. Not only was Rahmon not the pre-independence leader of Tajikistan, but he wasn’t even a high ranking official. So how did he outfox all the Tajik Soviet oligarchs and emerge as the undisputed head of independent Tajikistan for 32 years and counting?

Apparently, the Soviet Tajik leadership was either a lot more chaotic or incompetent than the leadership of the other Stans, because from August 1991 to November 1992, Tajikistan went through four administrations and Rahmon popped out on top by being boring and ostensibly controllable.

The first independent Tajik leader, who ran the pre-independence Tajik Soviet, backed an unsuccessful coup attempted against Gorbachev in the dying Soviet Union, and was subsequently thrown out of power ten days into independence. The second leader tried to destroy the communist party and launch a new Tajik nationalist regime, but one month into his term, he was overthrown in a coup by a hardline communist party rival who became the third leader of independent Tajikistan. He had previously run the Soviet from 1982 to 1985 (until he was removed for corruption) and seemed to have a stronger political base. He held an election to legitimatize his power, but it was so blatantly rigged that it more-or-less triggered the civil war. He still managed to last a year before he was couped by his regime cohorts for making a big mess and as a means of hopefully placating the Islamic rebels who were advancing on the capital. In his place was put another communist party stooge, but he too stepped down after a few weeks as a further act of placation.

These last two hasty resignations were announced and enacted while the Tajik government was literally falling apart. The resignations couldn’t be fully legally ratified because provinces in rebellion weren’t sending representatives to Dushanbe. AK-wielding rebel bands were so close to the capital that the Tajik leadership fled to Khujand, a loyalist stronghold with a current population of under 200,000, where it was hoped that sheer mountainous terrain would keep the rebels at bay.

It was in this auspicious moment, in late 1992, that Emomali Rahmon (again, then Emomali Rakhmonov) came to power. He was not elected, but merely appointed as acting president in a metaphorical smoke-filled backroom meeting of party apparatchiks. There is little public information about how choosing a guy with no leadership experience, no army experience, and virtually no public recognition would salvage the increasingly dire political situation.

My idle speculation – maybe he was the most ‘salt of the earth’ of whoever was left in the administration since he wasn’t obviously corrupt and had been managing farmland in his hometown a few years ago, while in contrast, the previous leader was an obvious Russian-backed USSR-era holdover. Speculation from my main source – Rahmon was put in place by a bunch of generals (ie. warlords) as a boring party stooge who would easily take orders. One of the generals referred to Rahmon as “nondescript” and assumed that he would be pushed aside when he was done being useful to the military.

In 1994, Rahmon was formally elected president in an obviously rigged vote which he nevertheless only won with 58%. To be fair, Rahmon had a tough time campaigning since he was literally unable to travel to most of his country since it was under rebel control that would shoot him on sight. Even Khujand, his one-time stronghold haven, became increasingly hostile, and Rahmon stopped visiting the region after two near-miss assassination attempts. So throughout the 1990s, he basically sat in Dushanbe and hoped the rebels wouldn’t reach him.

In 1997, Rahmon signed a UN-mediated peace treaty with the rebels and something seemed to awaken in the mid-40s party functionary. I can’t find a ton of details on his strategic maneuvering, but for the next 15+ years, Rahmon embarked on a surprisingly successful political consolidation campaign which forced the downfall of both his enemies and former allies one-after-the-other.

The break from the military shackles occurred during two unsuccessful military coups in 1997 and 1998. Rahmon then had to deal with his political opposition which he was treaty-bound to permit into the national legislature as part of the peace agreement to end the civil war. But in the 1999 election, Rahmon won 97% of the vote and his party massacred the opposition in the polls, either because Rahmon was a dazzlingly charismatic leader or because he blatantly rigged the whole thing. The opposition complained and the international press condemned Rahmon; he responded by ignoring everyone and apparently doing enough dirty work behind-the-scenes to prevent a second civil war. In 2003, Rahmon launched a national referendum to let him run for more terms, which of course was passed with an overwhelming majority. Then Rahmon won more blatantly rigged elections in 2006 and 2013.

In 2015, Rahmon finished off the last of his serious opposition. Allegedly, the deputy defense minister tried to launch a coup with the backing of the Islamic opposition party, though it’s unclear whether this actually occurred. Rahmon’s loyalists defeated the putschists and arrested 170 top military and political officials while virtually the entire rest of the Islamic leadership fled into exile. At that point, the path was clear for Rahmon to establish complete control over Tajikistan for his political dynasty. In 2016, he amended the constitution again to give himself official near-dictatorial powers, and then he won another blatantly rigged election in 2020, and before anyone knew it, this random party functionary had been running Tajikistan for over two decades.

Not much is known about Rahmon’s big political maneuvers, like the 2015 military/political purge, but there is even less information available on the mechanics of Rahmon’s corrupt dealings. Regardless, the end result is obvious to everyone both inside and outside of Tajikistan. In a masterwork of old-school clannish grifting, Rahmon has virtually complete control over the Tajik state and economy, including all government agencies and major companies, through a network of loyalists, nearly all of whom are either his direct family members or in-laws.

To his credit, Rahmon seems to mostly retain the Soviet dedication to gender equality. Rahmon’s oldest daughter is the head of his executive office and her husband is the deputy head of the National Bank of Tajikistan. His third daughter is the deputy head of the Foreign Ministry’s International Organizations Department, and her husband is the head of the National Winter Sports Association. His sixth daughter is the deputy head of Orienbank, the largest commercial bank in Tajikistan, a position she undoubtedly meritoriously earned at age 23. A son-in-law runs the country’s fuel monopoly and another son in law runs the country’s railways.

But the second highest spot on the Rahmon clan corruption hierarchy belongs to the president’s eldest son, Rustam. He is fortunate enough to currently be the mayor of Dushanbe and the head of the rubber-stamping national legislature. Rustam is also, ironically, the previous head of the Agency for State Financial Control and Combating Corruption, and has a major general rank in the military despite having no military experience nor training.

Rustam is fully expected to take the reins from his father whenever he retires or drops dead. His legislative post makes him the official successor and numerous online articles mark him as the unofficial successor. One local I spoke with also said that Rustam would undoubtedly be their next president, and though this individual had his doubts about Rustam’s competence compared to his father, he still supported Rustam’s ascension since the alternative would likely be a chaotic power struggle.

The elder Rahmon may lead a cult of personality, but he’s actually pretty low-key in his dictatorial antics. Rustam can’t say the same; the man is a big fan of soccer, so much so that he co-founded Dushanbe’s team and was its captain for many years. The team was generally successful and really hit its stride in the 2010s when it won five championships, most of which occurred after Rustam retired from active play in 2012.

The problem is that Rustam’s team has benefited from quite a few suspicious calls from referees, so much so that Dushanbe has had numerous riots after the team’s bullshit wins. After one particularly egregious match, brave fans of the opposing team started chucking rocks at Rustam and his teammates until the police fired their guns in the air and beat the shit out of the hooligans, injuring 16 and arresting 20. Shortly afterward, the elder Rahmon dutifully backed his son and signed a new law increasing legal penalties for sports-related mayhem.

In another instance, five of the players on one of the best Tajik teams were hit with temporary bans and fines after playing too well against Rustam’s team. Officially, they were accused of playing in a “very rude and mean” manner.

Like a greedy Crusader Kings player, Rahmon hoards as much wealth as possible in the hands of himself, his family, and his in-laws, but plenty of it also slips out to key non-familial loyalists. For instance, Qosim Rohbar is a former provincial governor and Agricultural Minister who operated as a “mafia kingpin” with Rahmon’s approval, and somehow managed to amass $8.5 million in a Swiss bank account on an official annual salary of $7,680. On a smaller scale, the President’s doctor’s son got into some trouble after bragging about his connections too loudly, so Rahmon dragged him in front of the national legislature and chewed him out for having four houses and three cars on a $2,400 annual salary as a customs official. Ultimately, Rahmon was pretty nice about it, merely scolding the guy with: “You will resign now! You are still young, otherwise you would be sent to prison for at least 15 years.”

Here’s Wikipedia on the current Prime Minister of Tajikistan:

“His wife, Ikhbolkhon Nazirova, owns two properties worth $1.4 million in Dubai. She also owns several properties in Tajikistan. Their daughter, Farangez Azimova, owns a villa in Dubai worth $5.4 million… The source of the couple’s wealth is unknown, as she has no known income and Rasulzoda, as a public official for 24 years, has been barred from engaging in commercial activities.”

It’s worth putting these numbers in perspective. No one knows how much the Rahmon clan is worth, but it’s nothing compared to Kazakhstan’s former president Nursultan Nazarbayev, who has personally amassed north of $10 billion (here’s $7.8 billion in a single company). But Kazakhstan with its oil and gas is a far wealthier country and therefore there is far more to plunder. Tajikistan is probably among the top 40 poorest countries on earth, a status that Rahmon cleverly parlays in his grifting, like when he got $13 million in food aid from USAID right around the same time he spent $92 million on a private jet.

In other words, the scale of Rahmon’s corruption is nothing to write home about by global standards, but the… I guess density is. Rahmon and his family and supporters basically have complete control over the Tajik economy, at least of everything above street-level businesses and the few foreign brands in the country. As a post-Soviet state, all of Tajikistan’s productive assets – its gold, coal, aluminum manufacturing, cotton, and energy production – were already in state hands at the start. It was easy enough to appoint loyalists to run these assets, and the meager privatization efforts in the past just made the corruption more formal.

My sense from talking to locals is that the Rahmon regime is suppressive though not to a crazy extent or anywhere near totalitarian levels. But maybe I’m underselling it. From the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project:

“There’s a great little anecdote that we include in one of the stories, a Western researcher was in Tajikistan, and his cleaning lady was in the apartment. Suddenly on the TV, a program by Umarali Kuvvatov was talking about the authoritarianism of the president and how the president was leading the country in the wrong direction. He remembers that the cleaning lady froze and for her, it was like seeing God criticized on TV for the first time. This is the environment that has been built in Tajikistan. The leader of the Islamic Renaissance party (the now banned opposition party) told me that it was like North Korea, people only see that Tajikistan is safe, the president keeps you safe, everywhere else in the world is chaos, everywhere else with religious opposition parties, Islamic parties, is just terrorism and extremism. Here in Tajikistan, everything is different.”

The report also claimed that former opposition leader Umarali Kuvvatov may or may not have been assassinated by the Tajik government while living in exile in Istanbul. There’s no conclusive proof, but he was shot in the head under mysterious circumstances two days after a bunch of his comrades were given long prison sentences in Tajikistan.

Based on my few conversations with locals, the Rahmons have done a good job recently of placating the masses by convincing them that they are sharing enough of the wealth. It’s far more likely that the government is benefitting from a temporary windfall that translates into more wealth for the Tajik people even if the corruption stays at a steady rate. And due to such corruption, it is extremely unlikely to me that Tajikistan will emerge as anything other than an impoverished raw resource producing state and Chinese colony for the foreseeable future.

Pamir Highway

I spent nine days travelling along the Pamir Highway with a driver and the aforementioned three Europeans. The journey was easily among the most beautiful in my life, with landscapes and views rivaled only by a handful of equally stunning places in the world such as Peru and Iceland.

There’s not much point in trying to describe such beauty through writing, but I’d summarize the visuals as desolate. The highway runs along and through mountain ranges and valleys with few people and little life in general. It looks primordial, at times other worldly. Despite being completely different geographic terrains, Iceland is probably the closest comparison for any other national topography, with a bit of Tibet thrown in. And like Iceland often does, the Pamir region would do very well as a stand-in for an alien landscape in film or television.

Another analogy to describe the Pamir landscape: sometimes it looks like god started making a chunk of earth, and then got bored and stopped halfway through and just left it like that for eternity.

There are green parts too:

As you might expect, the highway is not particularly well-maintained along its 750 miles. I wasn’t actually sure if we were on the highway itself the whole time or if we ventured onto side roads, but we soon discovered that the paved roads were actually worse than the dirt roads. Sure, the dirt roads shook us around, but the paved roads had the deep and sudden potholes that really knocked our socks off. During some stretches of dead straight, perfectly flat paved roads, we traveled at an average of 20 miles per hour for hours at a time.

The roads would have been worse if it weren’t for – who else? – the Chinese. Their road crews swarmed the length of the Pamir Highway filling in cracks and paving new stretches. I presume that virtually all of the tunnels, some of which are miles long, were built by the Chinese, or maybe the old Soviets. At one point, we had to wake up at 4 AM to get through a tunnel before 6 AM when the Chinese would start working on it and blocking it entirely until noon.

However, Tajikistan’s best tunnel isn’t on the Pamir Highway at all; it’s to the north of Dushanbe. The 3.1 mile Anzob Tunnel is also known as the Tunnel of Fear or the Tunnel of Death for its faulty ventilation which has killed numerous people during traffic jams. Some choice quotes from dangerousroads.org:

“The poisonous air in the tunnel is barely shifted by one solitary fan somewhere in the middle of the tunnel, which gives some, but not sufficient, movement to the air.”

“There are no traffic lights to regulate traffic through this section, nor is there an ordered tidal flow of traffic being allowed to enter the tunnel; instead, anarchy prevails in the darkness.”

“Even in good weather conditions, the tunnel is flooded, turning the giant potholes in the unfinished road into invisible death traps. Unmarked drainage channels waiting to swamp your bike. The tunnel lacks proper lighting and ventilation, and breathing is hard and painful due to the thick mixture of exhaust gases. Most drivers go as fast as they can, as in any other Central Asian country. Avoid the potholes, particularly in the winter time here. Your whole SUV can submerge if you drive in the wrong place. There are no road markings, so driving on the left or the right are optional, with the middle being the common choice.”

Sadly, I think I was mostly spared from these conditions since improvements were made to the tunnel in 2018. I got to experience it during a day trip from Dushanbe to Iskanderkul (a resort lake), and while it was an eerily dark and long tunnel, I didn’t notice any noxious fumes or watery death traps.

One of the highlights of the Pamir Highway is seeing other countries. I caught a glimpse of a mountain peak in Pakistan, I saw long stretches of desolate wasteland ceded to China, but of course, most interestingly, I saw Afghanistan, and even some Afghans (though no Taliban).

The Afghan-Tajik border is understandably tightly guarded, at least on the Tajik side. There are periodic military outposts that stopped our vehicle and checked our passports, plus Tajikistan requires a special permit for foreigners who travel through the area (the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region Permit or GBAO Permit). Presumably this is to clamp down on any radical Islamic activity that might be encouraged by neighboring Afghanistan. Nevertheless, in at least one spot on the border, there is a weekly market day in which Afghans and Tajiks mingle freely under the guard of both the Tajik military and the Taliban. I would have loved to attend, but unfortunately the timing didn’t work out for us.

I saw an eagle, two wolves, four snow leopards (in a preserve), lots of sheep, lots of goats, lots of cows, lots of yaks, lots of dogs, a few cats, but the coolest of all were the Marco Polo Sheep. I saw two herds of these big fuckers. This is the best picture I could get:

Here’s what they really look like:

Another highlight was climbing to the base of Lenin Peak, which reaches to almost 23,000 feet at the top. It used to be one of the tallest mountains in the Soviet Union, but the tallest was Stalin Peak (also known as “Communism Peak”), which is now called Ismoil Somani Peak after the warlord who brought Islam to the region.

Like in Peru, I took seizure medication that doubles as a preventative and active treatment for altitude sickness. Actually, I idiotically took the same exact medication, as in from the very same bottle, which is now over three years old. Which is why it didn’t work this time and I was huffing and puffing up three mountains on three separate hikes while the Europeans ran laps around me.

Border Crossing

I left Tajikistan through the Kyzyl-Art Pass at the Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan border. It was not an easy process and I had a bit of a border adventure, but god knows I haven’t been the only one.

The militaries of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan periodically get into surprisingly large literal battles on their border, mostly over disputed claims to resource deposits, primarily fresh water. In April 2021, a largely unknown catalyst resulted in 55 deaths and 4,000 civilian displacements. In July, another small skirmish resulted in the death of a single Kyrgyz soldier. A brief peace was made but then broken in January 2022 when another fight left two dead and dozens wounded. In March, another outbreak left a Tajik border guard dead. In June, there were two more small skirmishes, resulting in another dead Tajik border guard. On a day in September, both sides of a border crossing accused the other of violating the demarcation zones, resulting in two more deaths and more than a dozen wounded.

Two days later, the shit really hit the fan as actual armies began assembling and President Rahmon ordered the Tajik military to seize numerous airports on the Kyrgyz side of the border. The Tajik military started its assault by launching artillery shells over the border at one of the Kyrgyz airports but seemingly was never able to actually invade. 137,000 Kyrgyz people were evacuated from the region and sporadic looting broke out in border towns. Tajikistan claimed that Kyrgyzstan deployed military drones for counterattacks. The casualty reports are conflicted, but Kyrgyzstan claimed 24 dead and almost 90 wounded.

Since then, the border has been relatively quiet but completely shut down for travel for native Tajiks or Kyrgyz. Only tourists can get through.

I find the whole thing incredibly weird, and all the more so since there are so few details about the conflict online. The border itself is extremely high and mountainous, often over 9,000 feet, and the border crossings are small and isolated. How did Tajik and Kyrgyz border units keep getting into situations that resulted in shootouts? How can two countries have so many military fights that result in direct casualties, including straight-up artillery barrages over the border, and not actually declare war on one another?

I have no idea. But the general international consensus is that Tajikistan is in the wrong and the conflict fundamentally stems from Rahmon maintaining territorial claims to border resources that Tajikistan has never controlled.

For what it’s worth from my extremely amateurish perspective, it seems like the Kyrgyz military could punch back a lot harder if it wanted to. I’ve traveled through a lot of poor countries and have seen a lot of poor militaries, but Tajikistan is the first country I’ve been to where most of the soldiers I’ve seen didn’t have guns. Seriously, of the 20+ soldiers I saw along the Pamir Highway and at the border, maybe 1/3rd actually had firearms while the rest just had knives. And of the better armed one-third, I swear, most didn’t have clips in their AKs. Meaning, they either carried no ammo or only a single round in the chamber. Also, the Tajik border facility was in shambles, and seemed to consist of a few concrete husk buildings and shipping containers. Some of this could be attributed to the fighting (there were shattered windows and what appeared to be bullet holes), but unless the Kyrgyz managed to blow up their toilets, the Tajiks really did piss and shit in a shallow hole in their barracks. I’m not talking about an ordinary hole-in-the-floor bathroom in a poor country, I mean an absolutely disgusting shit-filled and covered hole that bordered on noxious.

In contrast, the Kyrgyz border guards seemed to have their shit together. Everyone was armed and appeared to have ammo, everyone was much more professional, the buildings were intact, the border-crossing processing room was clean and neat, there were real fences around the whole facility, and though I didn’t go to the bathroom on the Kyrgyz side, I couldn’t imagine theirs being worse than the Tajik’s side.

The impact of all this border warfare on me was that it made an already difficult-to-cross border substantially more annoying. My Pamir tour driver was a Tajik and therefore legally barred from crossing the border, and we had to meet a new driver on the Kyrgyz side of the border, who was a Kyrgyz and therefore also legally barred from crossing the border. But that’s ok, we should have just been able to drive up to the Tajik side of the border, get out of the car, and walk across the border to the Kyrgyz side, right?

Wrong. Because between the two borders is a 14 mile no man’s land gap.

That’s too long to walk of course, but fortunately, presumably through some finagling and possible bribery, the tour company worked out a compromise where we could cross the Tajik side by car and go to a meeting place about half a mile into the no man’s land where we would meet the Kyrgyz car. To ensure no espionage or military adventurism was at play, an armed border guard would hop into both our car and the Kyrgyz car, not because of me or my European tourist companions, but to monitor our respective drivers. Our guard on the Tajik side not only had a gun, but one with ammo (or at least a clip). So we drove to the border, picked up the armed border guard, and then met our Tajik driver in no man’s land, right?

Wrong. The problem is that the Kyzy-Art Pass is at around 13,000 feet. Even in the early summer, it’s still covered in snow and sometimes gets hit by snowstorms, such as exactly when my group tried to cross the pass. When we arrived, the visibility was maybe 15 feet in any direction. Beyond that, everything was pure white. In the checkpoint, we could see the various huts and cargo containers and were alright, but once in no man’s land, we were in a white oblivion, one which happened to have various cliff’s edges within 20+ feet.

Yet our (amazing) driver still believed we could make it to the rendezvous point. So we got our passports stamped, and then with our armed border guard bringing the car up to six passengers, we attempted to drive through about a foot of snow (and rising) in sheer whiteout conditions. This lasted thirty seconds until our driver stopped and then spent a supremely impressive thirty minutes laboring outside in the snowfall to put chains on the tires and dig holes in the snow every ten yards for about 100 yards ahead to lay a path for our progress.

Aside – I’ve been asked a few times if I’ve ever had a gun pointed at me. The answer is now technically “yes.” Through bad luck, I ended up in the middle back seat while the armed boarder guard sat in the front passenger seat. In yet another instance that made me doubt the fighting fitness of the Tajik military, the guard placed the butt of his AK on the floor near his feet so the barrel was facing up and toward the rear of the car. Which is to say, the AK was pointed at me while we were driving through a foot of snow with lots of bumps and shakes and fits and starts and jerking and revving the engine to get traction. I prayed that the ammo clip really was just for show.

Eventually, the driver got back in the car and we pushed onward for 100 yards. Then he stopped and did the same thing with the hole digging again. Then we went another hundred yards. Then we stopped and did the hole digging again. Then we went another hundred yards, and then the driver declared that the slope was too steep, but we were within theoretical walking distance of the rendezvous point. So we could just take all of our bags out of the car and power through the last few hundred yards on foot in white oblivion until we got to the other car, right?

Wrong. The problem was that we didn’t know if the other car was there. The other side of no man’s land was more than 13 miles long, and given the weather conditions, we had no idea if the other car had made it to the rendezvous point. It seemed impossible to me, but the driver assured us that “maybe he made it.” So we could just call the other car and ask if he had arrived, right?

Wrong. We had no way to contact the other car. There was no phone service here. But surely the Tajik border guards had some means of contacting the Kyrgyz border guards on the other side to ask if a vehicle had passed into no man’s land, right?

Wrong, they didn’t, or at least not at that time. The checkpoint’s communication system was based on solar power, and while I applaud their environmental consciousness, that seemed like a poor choice for a Himalayan Mountain pass.

So our driver hiked through the snow on his own to the rendezvous point to see if the other car had arrived. We watched him disappear into the white nothing while we sat in the car with the armed guard, his AK still carefully pointed at my chest. Then the driver came back and told us… nope. He wasn’t there.

So what could we do? Our driver opted to wait, which we did for an hour, then the driver hiked back up the rendezvous point and back to us, and confirmed that, again, the other car wasn’t there.

So what could we do then? We drove back to the checkpoint, let the border guard out, and waited for three hours for the theoretical backup meeting time. Our driver asked the border guard if we could wait inside one of the buildings and we were refused, so we sat in the car. As further punishment, the guards let us use their hideous hole-in-the-ground bathroom, but to their legitimate credit, they did eventually give us a bunch of biscuits and tea and candies, which was super nice.

Then the border guard got back in the car, was nice enough to point his AK away from me, and rode with us in another harrowing attempt to reach the rendezvous point, which had the same result. Across the roughly six hours we sat at the border and near the meeting point, we never had any means of communicating with the other vehicle, so at that point, we gave up and returned to the small internet-less Tajik village where he had spent the previous night, which required about an hour drive back down the pass. We were briefly concerned that we had already gotten our passports stamped out and therefore we couldn’t legally re-enter Tajikistan, but our driver somehow took care of that.

The next day, we drove an hour back to the border crossing and were thrilled to see that the snowstorm was over and we had perfect visibility with a beautiful baby blue sky and bright sun overhead. We were less thrilled to see that the snow had amassed to over two feet of fluffy powder in some places and it was therefore an open question whether either car could reach the rendezvous point. We were once again thrust into a communications blackout, but our driver assured us that yesterday had been a tragic two-time near miss, and now the meeting times were even better coordinated.

We once again picked up a border guard (this time a different guy) but now our drive through the white void was a pleasant drive through a winter wonderland. That is until we reached roughly the same point our vehicle did the day before and the slight incline made progress challenging. I don’t know how to drive through snow and frankly I’m not sure if our driver did either, but his technique of charging forward until the tires uselessly spun and then backing up 30 yards and then charging forward again to grab a few more yards of progress proved relatively effective as we traveled about 150 yards forward over the course of 30 minutes.

Eventually, we made it to the rendezvous point. The other car wasn’t there, but the driver said this was to be expected. This time, he had it on good authority that the other car was waiting for us about 1.5 miles away at the bottom of the hill (ie. closer to mountain) that we were currently at the top of. We would have to take a mild leap of faith and walk down the hill through the snow to where the driver was supposed to be. If, for some reason, the driver wasn’t there, I guess we would have to walk the remaining 12ish flat miles through the snow to the Kyrgyz checkpoint. Also, the driver couldn’t come with us because Tajiks and Kyrgyz weren’t allowed to go beyond this point in the no man’s land, so we were on our own.

It all worked out in the end. The 1.5 mile trek with my full travel pack through two feet of snow was not one of the easier hikes in my life, but it was all downhill so it wasn’t too bad. One of the Europeans had a much harder time than me, not because of the physical exertion, but because he had lost his sunglasses, and so within 15 minutes his eyes were in pain from the light bouncing off the snow.

The driver was where he was supposed to be and was accompanied by a very friendly Kyrgyz border guard who took a bunch of pictures with us and did not accidentally point a gun at me. After another 0.5 miles of walking, we made it to his vehicle and then slowly drove the remaining way on a flat but snow-covered road until we reached the Kyrgyz border.

Questionable Claims

A series of questionable claims were made to me by Tajikis. Here are my fact checks.

Claim 1 – The swastika was invented in Tajikistan.

A tour guide in a fort museum pointed to a row of swastikas in an old stone facade and then claimed that the swastika itself originated in Tajikistan.

The swastika is (or at least was) officially backed by the Tajik state in its effort to promote a unique Tajik culture and nationalism. Of all the possible angles to take, the government has seen fit to embrace its allegedly Aryan ethnic heritage and declared 2006 as “the year of Aryan civilization” to “study and popularize Aryan contributions to the history of the world civilization, raise a new generation (of Tajiks) with the spirit of national self-determination, and develop deeper ties with other ethnicities and cultures.”

Sounds like a true triumph of the will. One particularly brave Tajik official proclaimed:

“We all know that fascism used this symbol for its purposes. This symbol therefore carries negative connotations for many…[but] we should not limit ourselves to only one interpretation.”

Still, I can’t find any evidence that the swastika actually comes from Tajikistan. At best, the swastika was invented by Aryans, which the Tajiks arguably are via their ethnic connection to Persians. However, my quick skim through the Wikipedia entry on “Aryan” indicates that the precise boundaries, nature, and scientific reality of Aryanism is somewhere between fuzzy and fake.

Note – Despite the government’s official support for the swastika 15 years ago, I didn’t actually see any swastikas in Tajikistan outside that one museum.

Verdict: Probably False

Claim 2: The “Taj” in “Taj Mahal” refers to the Tajik people.

This claim was made by a tour guide in the Pamir region. He was unclear on the specifics.

The Taj Mahal was completed in 1653 by a Mughal Emperor for his wife. According to Wikipedia, the precise etymology of the name is unknown, but the best guess is that “taj” is derived from a mixture of Arabic and Persian to mean either “crown,” “illustrious,” or “illuminated.”

However, Tajik is a Persian language, so maybe there’s a connection? The Wikipedia article on Tajikistan says that “Tajik” probably referred to a Persian tribe but “the Library of Congress’s 1997 Country Study of Tajikistan found it difficult to definitively state the origins of the word “Tajik” because the term is ’embroiled in twentieth-century political disputes about whether Turkic or Iranian peoples were the original inhabitants of Central Asia.'”

I tried some other Googling and found a random Facebook post claiming that “The builder of the Taj Mahal was from Khojand,” a city in Tajikistan. But the Facebook page’s own source only says that Ustad Ahmad Lahori‘s father was from Khojand. Lahori himself was unsurprisingly born in Lahore (modern-day Pakistan) and his Wikipedia page says nothing about Khojand.

Verdict: Probably Completely False

Claim 3: Tajikistan is an emerging tourist hot spot and it’s a good thing I visited when I did because soon the country will be swarmed by tourists

I heard this claim from my Pamir tour driver, at least two other random Tajiks, and two European travellers.

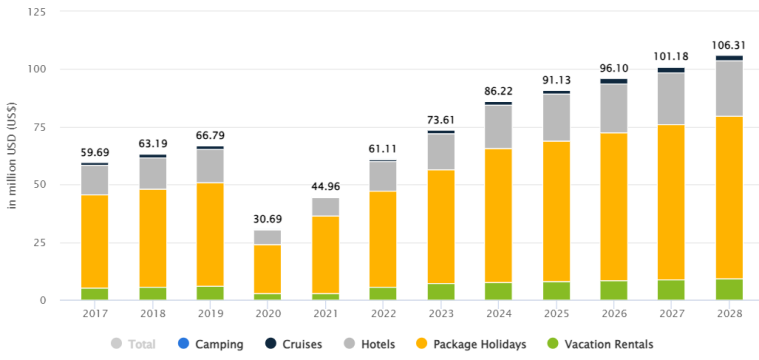

Tajikistan’s Wikipedia page doesn’t mention tourism, and the Tajikistan economy Wikipedia page only has a small tourism section that provides no statistics. The World Bank has figures that usually end around 2020 showing a paltry tourism industry; the “number of arrivals” chart ends in 2018 at a peak of just over 1 million. Statista provides this chart for Tajikistan’s national tourism revenue:

The World Bank’s rankings of every country by tourism revenue lists Tajikistan at $102.4 million in 2020, around the same level as Belize, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic, and… Bermuda? How can Bermuda possibly make less tourism money than Tajikistan? And how is Tajikistan listed at over $100 million when, according to Statista, it has yet to surpass $74 million in any year? Are all these figures messed up because of Covid? Are tourism revenue estimates just really unreliable in certain countries? I don’t know.

(Side note – dead last on the World Bank’s list of countries by tourism revenue is none other than… Guinea. Which, as I’ll never get tired of pointing out, might be one of the only countries on earth without telephone lines. Also, Mauritania is ranked seventh to last and Guinea-Bissau is 14th to last.)

Putting the numbers aside, I can definitely see the argument for Tajikistan’s impending tourist popularity. Right now, it’s firmly in the “hidden gem” category for travellers due to its beauty and remoteness. The next step is to gain popularity due to travel bloggers and YouTubers and move more into the mainstream, as is the trend for any naturally pretty place that isn’t too politically unstable.

While travelling throughout the Stans, I met few non-Russian tourists, but every single one of them was an experienced traveller: a digital nomad living in Georgia, a Swiss guy making his way to Thailand, a Spaniard who had been all over the world, an American missionary installing wells, etc. I doubt any one of them had been to fewer than 30 countries. If I go back to Tajikistan ten years from now, I doubt the traveller cohort will be the same.

Verdict: Probably True

Claim 4: Knowing me turns men into womanizers.

This claim was made by a Tajik high schooler with highly questionable English skills, who, after meeting and talking with me, an American, proclaimed that he would tell everyone in his class about his encounter, which would make him very popular, and thus he would soon become, in his own words, “a womanizer.”

I know many people, and to my knowledge, very few of them are womanizers. I cannot speculate on the causality at play.

Verdict: Mostly False

Miscellaneous

- In Dushanbe, people mostly speak Russian, while outside the capital, people mostly speak Tajik, though anyone educated speaks both. I’m told this trend between Russian and the main local language carries throughout the Stans (except maybe Turkmenistan).

- Dushanbe was previously known as “Stalinabad” from 1929 to 1960.

- “Dushanbe,” derives from the Persian word for “Monday,” which was the traditional market day for this settlement on the Silk Road.