I think whaling is really cool. I can’t help it. It’s one of those things like guns and war and space colonization which hits the adventurous id. The idea that people used to go out in tiny boats into the middle of oceans and try to kill the biggest animals to ever exist on planet earth with glorified spears to extract organic material for fuel is awesome. It’s like something out of a fantasy novel.

So I embarked on this project to understand everything I could about whaling. I wanted to know why burning whale fat in lamps was the best way to light cities for about 50 years. I wanted to know how profitable whaling was, what the hunters were paid, and how many whaleships were lost at sea. I wanted to know why the classical image of whaling was associated with America and what other countries have whaling legacies. I wanted to know if the whaling industry wiped out the whales and if they can recover.

This essay is the result. It is over 30,000 words long, a new record for my blogging. It’s broken into seven parts linked here:

Part I – Economic Value of a Whale

- Breakdown of the parts of a whale which have been harvested and commercially traded throughout history

- Description and valuations of whale oil, meat, baleen, and other resources

- Attempts at estimating quantities of resources extracted from a single whale

- Breakdown of the whale hunting methods throughout history

- Shore hunting, ocean hunting, and technological evolutions in hunting

- The many ways whale hunting can go wrong

Part III – Early Whaling History (6,000 BC-1700 AD)

- Overview of the origins of whaling

- Estimated value of a beached whale

- The commercial success of Basque whaling

Part IV – The Anglo Whaling War (1700-1815)

- Tracking the ascendancy of British whaling based on subsidies, tariffs, and military dominance

- Tracking the challenge of early American whaling based on innovation

- Explanation of why American whaling triumphed

Part V – The Golden Age of Whaling (1815-1861)

- Examination of the high point of global whaling, when whaling was one of the most important industries on earth

- Most in depth description of the economics and experience of whaling – 50% labor desertion rate, highly inconsistent payout matrix, 6% of voyages never returned, etc.

- Golden Age whaling did not have a significant impact on global whaling populations

Part VI – The Industrial Age (1865-1986)

- Fall of US dominance, rise of Norway and then European competition

- Overview of early attempts to restrict whaling for environmental purposes, and why they failed

- Collapse of whaling population, estimated species populations before and after industrial whaling

Part VII – Modern Whaling (1987-Present)

- Present state of whaling legality and population impacts

- Norway and Japan continue to hunt whales for opaque cultural reasons

- Commercial whaling can return, but I’m not sure if it should

As with my deep dive into K-pop, I advise that if you are interested in whaling, but not that interested, you should skip some sections and focus on others. Parts I and II are short and get into the fun nitty-gritty details of the practice of whaling. Parts III and IV are more about the history of the industry and how it interacted with politics, trade policy, etc, and are the most easily skipped sections. Part V is the longest and (IMO) most interesting section; it’s both an overview of American whaling and a deep dive into the economics of the industry, including crew payouts, profitability, venture earnings, and the impact of whaling on the global whale population. Part VI and VII bridge the gap between the high point of whaling and its near death in the modern age.

My two main sources are In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 by Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter, and Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America by Eric Jay Dolin. The former is more for statistics, detailed industry breakdowns, and whale population figures. The latter is more for color commentary, and since I listened to it on audiobook, my citations for it don’t include page numbers. Yes, apparently leviathan is such a good symbol/metaphor for whales that both books used it in the title.

As with all my research posts, I’m open to comments, suggestions, and corrections regarding anything I’ve written here. I tried to stay close to the texts and numbers, with my speculations usually noted as such. I’m coming at whaling and maritime history as an outsider, so it’s entirely possible that I’ve made mistakes, and I’d appreciate having them pointed out.

NOTE – There are lots of pictures and paintings of dead and dying whales throughout this post.

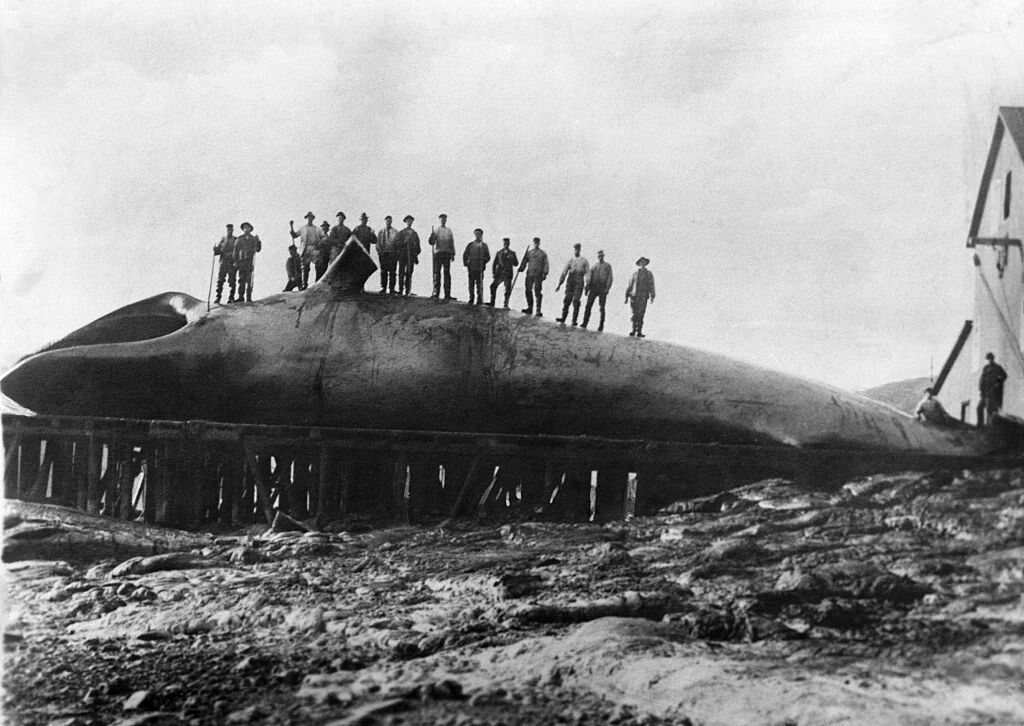

![A blue whale lies on the flensing platform at the Grytviken whaling station on the British island of South Georgia near Antarctica, 1917 - [3507x2182] : HistoryPorn](https://i0.wp.com/i.imgur.com/pWqVtlI.jpg)

Part I – Economic Value of a Whale

You have a dead whale in front of you. What can you get from it? What’s it worth?

Whale Oil

Throughout history, whale oil was usually the most valuable part of the whale and the primary objective of whalers.

Whales are mammals that almost exclusively live in cold oceans (no whales live near the equator), so they need ample insulation to keep their bodies warm. Hence all whales have blubber, an extremely dense layer of fat ranging in thickness from two inches to over one foot.[1] Just as your skin contains oil, so does whale blubber, though vastly larger quantities of it. This whale oil can be extracted through a process called flensing that consists of slicing the blubber into pieces and boiling it. Modern whalers use machines for this process, but back in the day they did it largely by hand. Cutting up the fattiest fat you’ve ever seen and boiling it over open flames is about as much fun as it sounds, especially since the whale was usually rotting during the process.

Due to the fattiness, quantity, and other chemical properties I don’t understand, whale oil was a uniquely effective oil for pretty much everything oil can do. Its primary historical use was as a fuel source for lamp lights since it emitted a fairly bright yellow glow at the expense of an unpleasant though not overwhelming odor.

Whale oil’s second major historical use was as a lubricant, particularly for heavy industrial machinery. Demand for lubrication rose in tandem with lighting during the early industrial revolution, and it was apparently more effective than animal fat or vegetable oil for the task.

Whale oil’s third major historical usage was as a key ingredient in margarine. Starting in the 1920s, margarine emerged in Europe as a viable butter alternative, especially after the destruction of World War I, and whale oil initially served as one of many fat bases, until in 1929, the margarine manufacturing process was refined so that whale oil alone could serve as the fat basis for the product. By the 1930s, 30% of British margarine and over 50% of German margarine was whale oil-based.[2]

Lesser historical uses of whale oil include the manufacture of soap, explosives, condiments, and medicine (especially to treat trench foot during WWI).

I had a hard time tracking down the average amount of whale oil in each whale. The lowest estimate I found in the mid-19th century American context was an average of 20 barrels per whale (one barrel = 42 gallons).[3] In Pursuit of Leviathan found a historical estimate of 25 barrels[4] which the authors still deem too low. Their preferred average estimate range is 33.6 barrels to 45 barrels for sperm whales (the most commonly caught species)[5] and 60-73 barrels for baleen whales (most other types caught).[6] On the lowest end, pilot whales provided only a few barrels of whale oil,[7] while right whales could reach well over 100 barrels.[8]

The quality of whale oil varies considerably by species, which impacted the brightness and smell of its light when burned and its viability for other uses. The faster a whale is flensed before it rots, the higher the quality of oil. Sperm whales produced the highest quality whale oil, followed by right whales and bowheads.

Spermaceti Oil

In the head of the sperm whale (which takes up about 40% of its body) the whale oil is so pure that it takes on a different chemical form and becomes a wax. It doesn’t even need to be flensed from the whale’s blubber, it can simply be scooped out from the decapitated sperm whale’s head. This substance is spermaceti oil, the highest quality oil to be found in any whales. It typically sold at 2-3X the price of high-quality whale oil.[9]

(Note – Spermaceti oil is technically a misnomer since it wasn’t an oil, but that’s what everyone called it.)

Spermaceti oil was most commonly used for lighting, either as candles or refined to a more oily form for lamps. It was considered the highest quality light of its day, emitting a bright white flame with no smell, and it was uniquely resistant to freezing in extremely low temperatures. Due to its price, spermaceti oil was almost exclusively purchased by wealthy people for personal use and governments for lighthouses. Benjamin Franklin wrote of his love of spermaceti candles as a nighttime reading light.[10]

Spermaceti oil could not be used in soap or margarine due to its chemical nature, though it had cosmetic uses in makeup. It was more often used as a lubricant and anti-rust substance for delicate, fine-tuned machinery (while standard whale oil was better-suited for heavy machines). In the mid-20th century, a small-but-steady sperm whaling industry persisted on demand from the aerospace industry where spermaceti oil’s extremely low freezing point proved valuable. Weirdest of all, spermaceti oil was used as car transmission fluid in the United States and Europe. When such use was banned in 1973, the number of transmission failures in American cars rose from 1 million in 1972 to 8 million in 1975.[11]

Ambergris

Ambergris is a waste byproduct formed in sperm whales. Sperms eat squid and cuttlefish which have beaks and other inedible components; these materials gather in the whale’s digestive tract, form a solid ball, and eventually get coughed up. So ambergris is essentially a combination of vomit and kidney stones.

But ambergris always has been and always will be the most valuable whaling product on a per-weight basis. This is largely owing to the sweet smell of aged ambergris which serves as an ingredient in high-end musky perfume. The substance is also alleged quite tasty, with eggs and ambergris being the favorite food of English King Charles II (who restored the monarchy after Oliver Cromwell and ushered in a notorious era of lax hedonism at court).

A single chunk of ambergris ranges in size from half an ounce to 110 pounds.[12] In mid-1800s America, a pound of ambergris sold for $200-600;[13] for comparison, the average 1850 American farmhand made $7.88-$13.55 per month with room and board.[14] However, from 1836 to 1880, the entire American whaling fleet produced less than a ton of ambergris, so it was never a major factor in whaling, just a random massive bonus for occasional lucky whalers.[15]

There’s a fun section in Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America where the author describes how ambergris was a scientific mystery throughout the world for centuries. The substance sporadically washes up on beaches pretty much everywhere there are whales, and so people from England to China were familiar with this extremely rare and valuable substance, but no one knew where it came from. There were lots of theories about monstrous fish, dragons, and the earth itself spitting up ocean gold, and it wasn’t until whalers started cutting open lots of sperm whales in the 1800s that the question was settled.

If the prospect of gathering ambergris intrigues you, you’re in luck! Ambergris is the only whale product that is still legal to harvest in most coastal countries.[16]

Whale Meat

Surprisingly, whale meat was not a historically important resource in whaling until the 1940s. While early whalers would consume the meat, the oil was always the main prize, and by the time commercial whaling got going in the 1600s, whale meat was often tossed overboard to make room for more oil. The meat that was harvested was typically used as animal feed. I couldn’t find any explanations for why such a potent form of calories, fat, and protein was neglected, but my best guess is that it simply wasn’t as valuable on a per-weight/volume basis as other whale resources.

The exceptions to this rule were and are various indigenous groups throughout the world which hunt whale as a basic food source, the Norwegians who took a liking to it in the mid-20th century, and most infamously, the Japanese. Whale meat is still currently consumed by these indigenous groups, Norway, Japan, Iceland, and South Korea, with average prices of about $9.00 per pound ($20 per kilogram), and top-tier whale meat selling for $27 per pound.[17][18] The current value of a single whale solely for its meat is estimated to range between $10,800 at the low end for minke whales, to $85,000 for large whales.[19]

I can’t find good official data on how much edible whale meat can be extracted from a single whale. The modern whaling countries don’t publish much on their activity; I tried extrapolating from Japanese aggregated data, but they catch a variety of whales and allegedly don’t report accurately anyway.

So, doing my best to guestimate:

- Whales have a bone mass of between 8% (dolphins) and 20% (blue whales) of their total weight.[20]

- Whales have a blood mass of 7% (dolphins) to 20.1% (sperm whales)[21]

- Let’s assume that if a whale was harvested for meat, all the blood would be drained. I know that’s not realistic, so take this as a low-bounded estimate.

- Let’s assume the rest of the whale is edible meat. This assumes:

- That the whale oil is left in the whale meat (it is edible, so that’s realistic)

- That all whale meat is edible (muscle, blubber, organs, etc.) – this is true, though probably disgusting, and even whalers who consumed whale meat definitely didn’t eat all the organs

- That all parts of the whale which aren’t bone or blood are of negligible weight.

So, guestimating on a right whale:

- Average full-grown right whale weight = 140,000 pounds[22]

- Since right whales are famously fat and slow, I’m estimating them to be on the higher end of the bone and blood levels, so let’s say 18% for both.

- 140,000*0.64 = 89,600 pounds of edible meat from a single right whale

Fun Fact 1 – Right whale testicles make up 1% of their weight,[23] so each testicle weighs around 700 pounds. The average American eats 222 pounds of meat per year (not counting fish),[24] so a single right whale testicle should cover a family of four for almost a year.

Fun Fact 2 – Whales ingest so much mercury that a single serving of whale liver could kill a full-grown man. There is 1,970 micrograms of mercury/gram of whale liver, which is 5,000X the Japanese government’s limit for mercury concentration in commercial food.[25]

Baleen

Whales either have teeth or baleen, a brush-like structure in the mouth which is chemically similar to hair or fingernails. Baleen whales take water into their open mouths, then push the water out through their baleen; this traps plankton, small fish, and whatever else they want to eat. While the toothy sperm whale was the biggest prize for whalers, baleen whales like rights, bowheads, greys, and humpbacks made up the bulk of hunted whales historically.

(Note – Baleen is often called whalebone, which is also a misnomer.)

After whale oil and spermaceti oil, baleen has typically been the most valued whale resource. Baleen has a hardness and flexibility which made it the closest commercial substance to plastic prior to the 1900s. Though best known for its use in corsets, baleen also found utility in “baskets, backscratchers, collar stiffeners, buggy whips, parasol ribs, switches, crinoline petticoats,” and cabinets.[26]

It was tough to find numbers on how much baleen can be harvested from a single whale, but I can work backwards from other figures in In Pursuit of Leviathan.

- Average amount of baleen harvested from a single 19th century voyage: 8,400.8 pounds[27]

- Number of baleen whales hunted on an average voyage – 15[28]

- 8,400.8/15 = 560 pounds of baleen per whale

Note – This figure represents the average of baleen whales caught on a single voyage, which would include multiple whale species of various proportions. This is a very rough estimate.

Whale Bone

Actual whale bones (as opposed to misnomered baleen) had no commercial use historically but were often harvested for scrimshaw, the sculpting and carving of bone. Given how boring whaling was (more on this in Part V), whalers often whittled their days away making surprisingly beautiful artworks which were nearly worthless at the time, but fetch a nice price today.

Modern Scientific Applications

Scientists in Norway, Iceland, and Japan have been hard at work studying whale oil, blubber, bone, baleen, teeth, and organs for cosmetic, nutritional, and medical purposes. For instance, Norway has developed whale-based nutraceuticals (similar to fish oil supplements), Iceland has figured out how to efficiently supplement animal feed with ground-up whale meat, and Japan has developed osteoarthritis treatments based on whale organs.

According to the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, all of these highly conspicuous scientific breakthroughs are part of a coordinated propaganda effort to rally public support for a global relaunching of the commercial whaling industry.[29] I have no idea if that’s true, but it sounds like a cool supervillain plot.

Part II – Hunting

What’s it like to hunt the largest animals to ever exist on planet earth? The following is an overview of the various methods and practices of whaling throughout history.

Shore Hunting

The first whales to be hunted by indigenous tribes were small coastal dwellers, like orcas, pilot whales, belugas, etc. These animals might be 70-200 pounds, and 4-8 feet long, so not much bigger than huge dogs.

Given the lack of available technology, the earliest hunting technique was the simplest: row up to a whale near the shore and stab it with spears until it dies. Then tie the carcass to the boat, row ashore, and cut it into pieces. This hunting technique seemed to be effective enough for calves (baby whales) and slower, older whales, and is still used to this day by a few tribes. Some slightly more creative tribes in the South Pacific would use boats and swimmers to corral dolphins and other small whales against the shore until they panicked and beached themselves.

Eventually, numerous civilizations throughout the world discovered drogue hunting, though the technique was ultimately perfected by the Basque people on the western border of Spain and France. A look-out man (or men) was stationed at a high point on the coast, like a cliff or a tower. He would stare out at the water for hours until he saw a whale, then he would ring a bell or set off some other alarm, and a team of hunters would sprint to the water, grab an elongated rowboat (typically around 15-ish feet long), and begin the hunt.

The men were equipped with harpoons and a drogue. A harpoon is an elongated spear with barbed sides designed to both pierce and stay lodged in the animal. A drogue is a flotation device, usually a wooden crate or barrel. The harpoons would be attached to the drogue by a rope.

The whales hunted by the Basque and others who used the drogue technique were far larger than the belugas and dolphins of the tribal hunters. For instance, right whales are typically well over 100,000 pounds and almost 50 feet long. They were far too big to be corralled by rowboats, and while a well-placed harpoon could kill a whale, it rarely did so.

Instead, the idea was to tie a harpoon to a drogue, get close to the whale, and then have a hearty seaman chuck the harpoon into the whale, and then toss the drogue overboard. The whale panics and flees, either swimming away or diving underwater. Either way, the drogue will weigh it down, and the harpoon in its flesh won’t stop hurting, so the whale will continue to swim and thrash. Eventually, it tires itself out and dies. The rights, bowheads, and other commonly hunted whales were so fatty that they nearly always floated to the surface after death, thereby allowing the whalers to latch it to their boat and row it ashore for processing.

Over time, whalers stopped using external objects as their drogues, and started using their own boats. I couldn’t find any explanation for this switch, but presumably the boats were a more effective drogue than boxes and barrels, especially as they began to hunt larger whales. Surely tying a 100,000+ pound beast to your own rowboat was riskier, but I guess the marginal yield was high enough to justify it.

Ocean Hunting

The Basque, English, Dutch, French, Germans, colonial Americans, and other highly-commercial societies all built prosperous whaling industries on the basis of shore hunting. They even established global operations on the model, with whaling outposts set up everywhere from islands in the Arctic Ocean to the Falklands.

But by the early-1700s, coastal whales were scarce enough, and whaling was competitive enough, that ambitious companies began experimenting with ocean hunting. This process was far riskier and more capital intensive, but offered vastly greater rewards.

This is when the whaling industry became what people usually picture in their heads, as they switched from a bunch of rowboats near the coast to giant ships on the deep blue sea. Whaling ships tended to be large and hearty, both because they went to dangerous waters, and because their cargo took up a lot of space. These ships carried whaleboats (note – a “boat” is a different thing than “ship”), which were updated versions of the elongated rowboats used on the shore. During the Golden Age of whaling, a typical American ship had a crew of 29 and 1-2 whaleboats (each carrying 2-3 men), while a British whaler would hold around 40-50 men.[30]

The core hunting principles weren’t dissimilar to that of shore whaling, except now the base was mobile. A whaler would sail to a region known to be flush with whales, a lookout(s) would scan the ocean for the animals, and when one was spotted, he would alert the men, sometimes literally with “THAR SHE BLOWS!”[31]

The boatsteerers (hunters), would then hop on their whaleboats on the deck and be lowered into the sea. They would row their highly maneuverable boats over to the whale, and then the highest-ranking boatsteerer (usually by seniority), would throw the harpoon into the rear or side of the whale, where the flesh was thickest and would hold the harpoon. Only after the harpoon was in the whale would they tie the rope to the boat, though I couldn’t figure out why they didn’t tie it ahead of time.

What happened next was eventually called the Nantucket sleigh ride based on its frequent occurrence in the Nantucket Bay off the coast of Massachusetts. Once the harpoon was in the whale, the beast would go ballistic, and either start thrashing about, dive, or swim away as fast it could. Sperm whales typically swim at a meandering 4 knots/hour (4.6 mph), but can sprint (?) up to 20 k/h (23 mph).[32] Keep in mind that in this early industrial era, the vast majority of whalers would have never gone that fast in their entire lives, unless they learned to ride horses at top speed.

While whaling as a whole was notoriously boring for crewmembers, this process of wearing the whale down was known to be an enthralling test of bravery, skill, and stamina. A few men in a narrow rowboat would hold on for dear life as colossal animals dragged them through the sea for tens of minutes to hours.[33]

Once a successful harpoon was landed and the whale was flipping out, one boatsteerer would go to the front of the boat, and the other to the rear. Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America emphasizes that it’s hard enough to stand up and walk around in a narrow rowboat on the ocean in the best of conditions, and was especially terrifying during a hunt. The guy in the back would steer the boat as it was dragged around by the whale so it wouldn’t capsize, and the one in the front would have a lance at the ready to eventually deal the killing blow. For reasons that baffle me, the harpoon rope was tied to a post on the back of the boat (or aft for all you nautical people) instead of the front. So the steerer would have to desperately keep the boat pointing toward the whale, or the boat would swing sideways and likely flip over. As added challenges, the taut rope would whip back-and-forth over the boat, creating a constant hazard for the crewmembers,[34] and the friction between the rope and the metal cleft on the boat was so great that it would often have to be periodically doused with water to stop the rope from setting aflame.

When the whale finally got tired, the whaleboat would pull alongside the whale, and the guy at the front would finish the beast off with a lance. Or at least that’s what happens if all goes well with the hunt. If all doesn’t go well…

- The harpoon falls out of the whale and it gets away

- A crewmember might panic during the “Nantucket sleigh ride” and cut the rope between the whaleboat and the whale, so the whale escapes

- The whaleship and whaleboats might get caught in a storm during the hunt, and either have to retreat or get wrecked

- The particularly hearty whale might swim for a very long time with the whaleboat dragging behind. Eventually, the whale and the boat go so far that they get out of sight of the main whaling ship, and the whaleboat gets lost at sea.

- A crewmember might fall overboard during the “Nantucket sleigh ride” and drown, or get eaten by sharks attracted by the bleeding whale

- A crewmember might fall overboard from choppy sea conditions

- A crewmember might get tangled in the rope attached to the harpoon, which might squeeze his body so hard that he loses a limb (surprisingly common)

- The particularly strong whale might dive and pull the whole boat underwater

- One whale might attack the whaleboats to defend another whale (relatively common with sperm whales)

- The whale might thrash around and capsize the boat

- The whale might turn around and bite the boat, possibly biting boatsteerers in the process (rare, but it happened occasionally)

- The whale might ram the whaling ship and sink it (extremely rare, but happened a few times)

- The whale might die, but before the whalers can harvest it, sharks might eat most of the flesh and oil

- The whale might die, but the harpoon and struggle tears much of the whale up, and its blubber and oil and blood and organs leak everywhere, and it’s really difficult to harvest

- The whale might die and sink underwater, losing the entire prize (more common with less fatty whales)

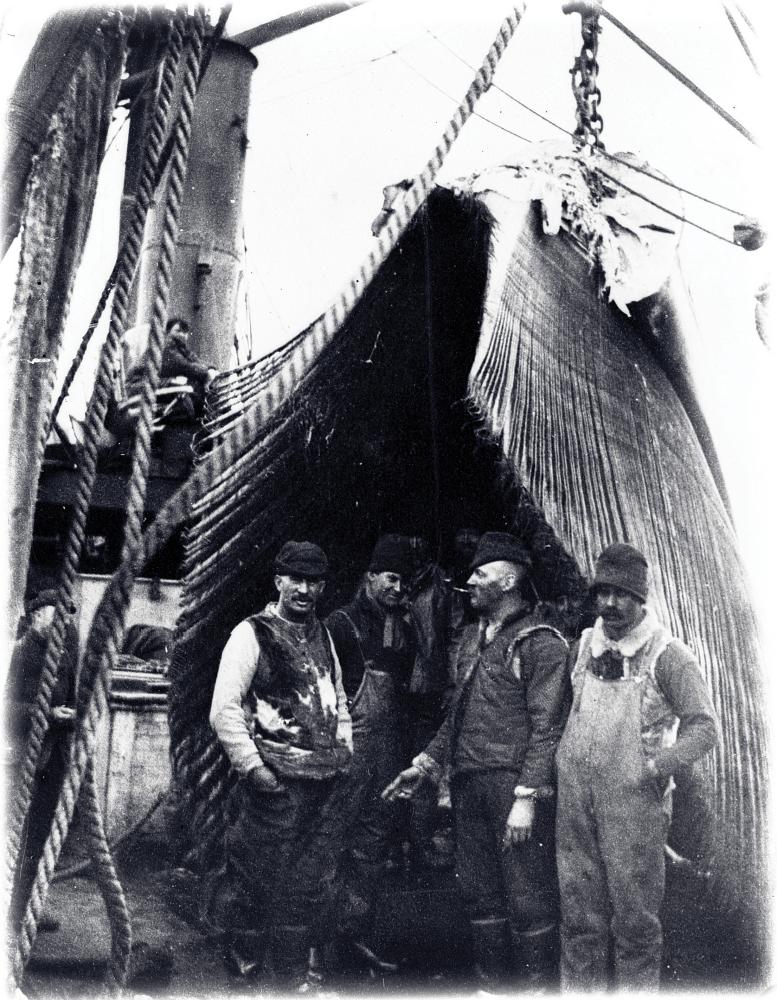

Anyway, once dead, the boatsteerers latched the whale to the whaleboat, and rowed in back to the ship. Then the boatsteerers using giant knives and saws to cut strips of whale blubber off the dead animal while it rolled in the waves beside the ship. At first, they could just hack at the whale’s skin and outer layers, but eventually they’d have to climb on top of, and inside of the whale to get at all the good gooey bits. Then they’d put the flesh strips in buckets which would be brought up to the main deck. If they had some tryworks (giant cast iron pots with some contraptions on them), they could boil the blubber to extract the oil. If not, they would dump the flesh directly into barrels.

Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America has a great section where it describes this whole process as the most disgusting job imaginable. A lot of whaling sucked for the whalers, but this was undoubtedly the worst part. Everyone is tired. Everyone is covered in blood and oil. Everyone smells worse than we can imagine. Everyone is slipping on everything. The whalers might be tempted to take a quick dip in the sea to clean off, but the water is nearly always filled with sharks and large fish taking bites out of the whale carcass. The whalers are either freezing their asses off in the Arctic, or they’re enduring the rapid rotting and subsequent smelling of the whale in warmer temperatures. Either way, the whalers had to work fast. Time really was money, because every second it took for them to cut up the whale was another second its oil decomposed from rot, exposure, fish, and water.

(The whalers would also have to cut out the baleen, potentially ambergris, and any whale meat they might want to keep, but those tasks were easy compared to the oil extraction process.)

This process of deconstructing a beast which likely weighed more than 100,000 pounds could take as long as three days. Three days of cutting flesh, holding flesh, boiling flesh, and packing flesh into up to 120 barrels. And then after it was all done, the whalers still had to mop up the blood, oil, guts, and flesh laying around the ship deck and in the whaleboats.

And once they were done with one whale, they had to immediately look for the next one. After all, a profitable voyage had to hunt dozens of whales. Plus, the longer the whale oil sat in barrels, the more it spoiled, and the more its quality degraded. It wasn’t until after the 20th century that whaleships had their own processing facilities, so the best the old whalers could do was strip the whale, squeeze out the oil, throw it in barrels, and hope it rotted slowly.

The one weird exception to this miserable process was the harvesting of spermaceti oil. Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America has an excerpt from a whaler’s journal where he waxes poetically about the joy of climbing into a decapitated sperm whale’s head and scooping out the substance. Apparently, it’s a warm space, it smells good, and the wax is quite good for the skin.

Industrial Hunting

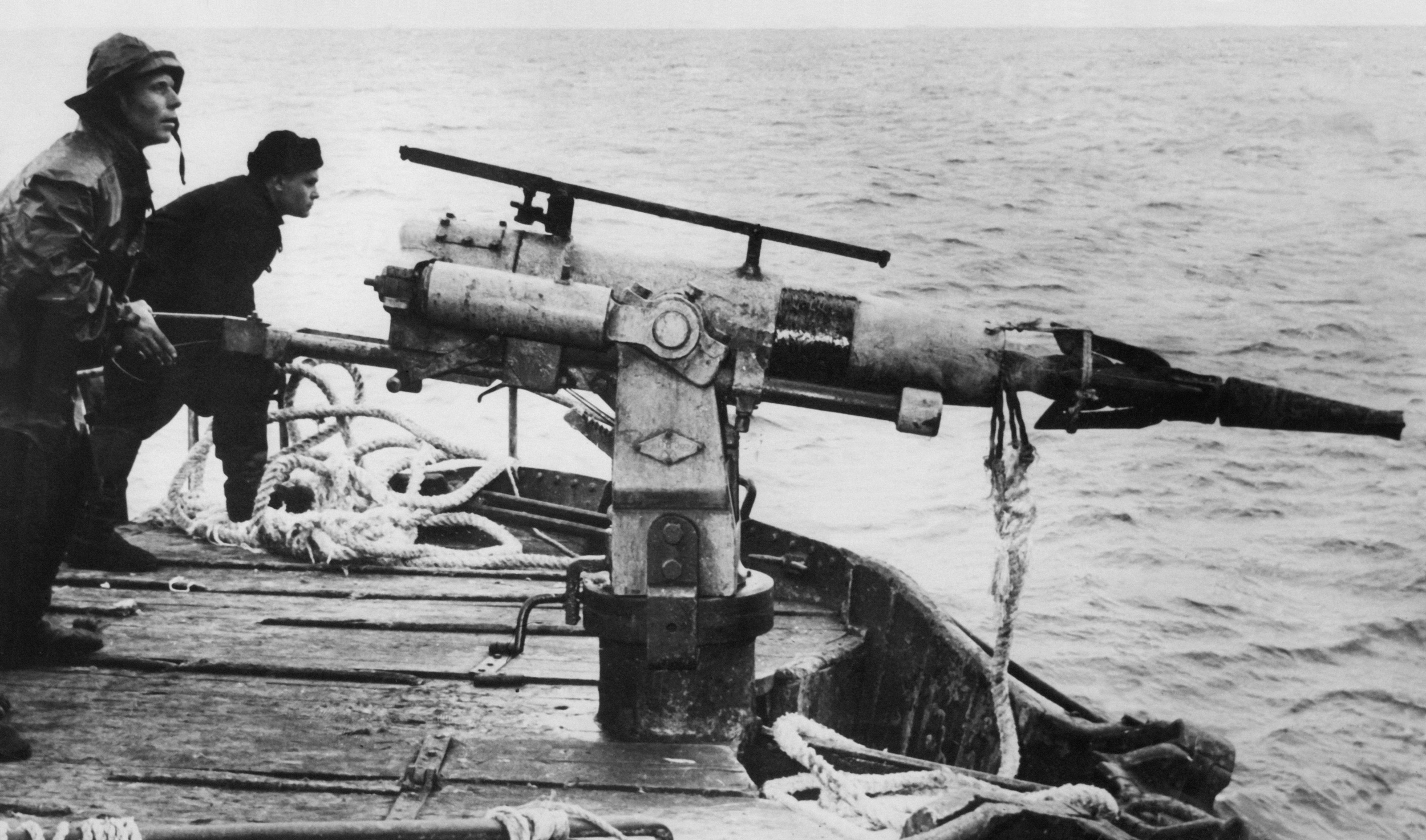

The Golden Age of whaling ended in the 1850s or 60s, and the industrial era slowly built until it peaked a century later. With greater technology came easier and more profitable hunts, though some would say less fair.

Ships got faster. Sails were replaced by steam engines and eventually modern gas-powered vessels. Aside from the obvious logistical advantage of moving faster, these ships also required far less manpower, and more importantly, opened up an entirely new category of whaling targets.

The rorqual family of whales, which includes the massive blue whales and small minke whales, was rarely hunted during earlier eras because they simply out-swam boats. It was not just fast vessels that were needed to take them down, but also fast weaponry. The harpoon gun emerged in the 1840s, but was slowly innovated and perfected, until a modern design with an explosive tip could easily insta-kill a whale in one shot.

Finally, the move to factory shipping transformed the industry. Instead of going through the hassle of extracting and storing the whale oil for later refinement onshore, factory ships could process the entire whale themselves. Whales could be spotted by sonar, quickly killed with explosive harpoons, dragged onboard, and rapidly flensed and processed so the whaler would return to shore with an already saleable final product.

Though animal rights activists tend to despise whaling, one of the legitimate advantages of industrial hunting is that it usually kills whales quickly… an explosive harpoon to the head will do that. But the method isn’t fullproof: among modern whalers, Norway reports that 20% of minke whales survive the first shot, and Japan reports that only 40% of all its whales are killed on the first shot.[35]

It’s not for the faint of heart, but if you want to see what modern whale hunting looks like, here it is:

Part III – Early Whaling History (6,000 BC-1700 AD)

7,700 years might seem like a long time for a single era of whaling, but it’s a good segmentation of the very earliest days of whale harvesting up to the start of whaling as an important industry in the Western world.

Diving and Stranding

Whale harvesting has occurred since the beginning of human civilization near oceans. A few tribes on warmer seas engaged in limited diving hunts for dolphins and other small whales. More commonly, northern tribes like Innuits, Ainu, and Native Americans engaged in drogue hunting. The earliest evidence of whaling dates back to cave paintings in South Korea which are estimated to 6,000 BC, and surprisingly show evidence of drogue hunting.[36] Modified versions of this method would be used throughout most of the whaling world until the late 1800s when harpoon guns and eventually explosive harpoons became prominent.

Despite the global prominence of whales, very few civilizations historically hunted whales at all, let alone systematically, likely due to its difficulty and lack of sufficient seafaring technology. But pretty much every cold-water dwelling people were aware of whales due to strandings. All species of whale periodically wash up onshore for reasons not entirely understood even by modern researchers. Sonar seems to have exacerbated strandings, but there’s plenty of fossil evidence that it has been happening since prehistoric times.[37]

Whale strandings were an enormous, incredible random bounty for pre-commercial/industrial people. Consider:

An average male sperm whale (one of the most commonly stranded species) weighs 90,000 pounds. Using my very rough metrics from the Whale Meat section of Part I, I’ll estimate that 64% of the sperm whale is edible (almost certainly an underestimate), which comes to 57,600 pounds. For comparison, a healthy 1,200 pound cow yields 640 pounds of meat[38] (including pure fat, but not including bone marrow nor organs – I couldn’t find good numbers) so a fully harvested male sperm whale = 90 modern cows in edible meat weight.

I wish I could further break down the comparison in terms of calories and nutritional content (surprisingly the data on whales does exist[39]) but that would require a lot of specific organ measurements, and that’s above my effort-willingness. But for one extremely rough guestimate…

Modern people on the carnivore diet eat 2-4 pounds of meat per day.[40] If we average that to three pounds of meat per day, a fully harvested adult sperm whale could feed 640 people on the carnivore diet for a month. Given that the average adult male medieval European peasant probably needed 2,900 calories per day,[41] we can assume they would get even more value from the stranded whale, especially since peasants would normally only eat meat once or twice per week.

On top of the meat, a juicy male sperm whale would yield well over 1,600 gallons of whale oil.[42] While I can’t find good info on how earlier whale harvesters used whale oil, there is evidence of it being commercially traded in Europe as early as 670 AD.[43] Presumably, people recognized that whale oil could be used like any other animal fat for lighting and soap, and I imagine 1,600 gallons of oil could go a long way.

Granted, all of this amazing material wealth began to degrade as soon as a whale stranded itself and died shortly afterward (from thirst, illness, or drowning once the high tide came in). Even 19th century commercial whalers had a hard time stripping whale carcasses of oil and meat before it dissolved into the most unimaginably foul-smelling piles of rotten flesh. And the 19th century whalers were pros; they knew how to cut and flense the whale to extract maximum value, so presumably random medieval fisherman and peasants weren’t harvesting optimally. And on top of all that, stranding harvesters had to worry about their whales exploding:

Nevertheless, a stranded whale was a colossal source of wealth for any pre-industrial people lucky enough to stumble upon one. People thought they were sea monsters, gifts from god(s), and generally representative of the awe and splendor of the world beyond the narrow scope of knowledge of prescientific people.

Stranded whales were so valuable that despite their rarity, many places established laws governing the ownership and distribution of harvests. In 1148 AD, English churches began establishing legal claims over any stranded whales found in their dioceses with the exception of the tongues which would be sent straight to the king. By 1315, all parts of all stranded whales were declared property of the monarch, and this is technically still the law today.[44]

(I found the tongue clause in multiple sources but never an explanation. I’m guessing it’s uniquely tasty. Atlas Obscura says whale tongue is a delicacy,[45] and Japanese whaling research data finds tongue to be among the most calorically dense parts of the whale.[46])

Basquing in Glory

The Basque people, located on and around the western border of modern-day France and Spain, are considered to be the first commercial whalers (as opposed to harvesting whales for consumption). As mentioned, the earliest records of selling whale resources date to 670 AD, just under 200 years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, when 250 liters of whale oil and whale blubber were sold from a Basque town to a French town.[47] While it’s possible that this sale was just the product of a fortunate stranded whale harvest, there is ample evidence of the Basque engaging in the most intensive whaling in the world from the early Middle Ages until the 1600s, and not petering out until the early 1700s.

Why did the Basque pioneer whaling? I have no idea, and I can’t find any good explanation. Sure, there were lots of delicious, easily hunted right whales in the Bay of Biscay, and the Basque were maritime people, but there were lots of whales in lots of places near lots of maritime people around the world.

Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America suggests that the Basque started whaling because of a loophole in Catholic law – Catholics were not permitted to eat “warm blooded meat” on religious holidays because it supposedly made them horny. And this being medieval times, by the end of the first millennium there were 166 religious holidays per year, which meant that Catholics couldn’t eat most types of meat for almost half of the year. Fortunately for the Basque, the church believed whales were fish and therefore not warm blooded, and thus were permissible to eat during holidays. Speaking from personal experience, whale meat tastes like an odd combination of beef and fish, so it served as a perfect meat loophole substitute for the Basque. This demand allegedly inspired the growth of the Basque whaling industry.

It’s a fun story, but it sounds a bit just-so to me. I assume this “warm blooded meat” moratorium was in effect throughout most or all of the Catholic world, so again, why did the Basque alone turn to whale meat? I don’t know.

Fortunately for the Basque, the most common whale in the Bay of Biscay was the right whale. The story that the right whale got its name because it is the “right whale to hunt” is apocryphal,[48] but the sentiment is correct. The animal is fat, slow, lives near the coast, stays near the surface a lot, and floats when it dies. A typical right whale produces 100-120 barrels of oil (more than 2X a big sperm whale)[49] and can weigh up to 300,000 pounds.[50] As you might guess, there are no longer any right whales in the Bay of Biscay, and only about 1,000-2,000 left worldwide.[51]

The Basque were the best whalers in the world, but only during preindustrial times when the volume of catches were nothing compared to the industry’s glory days. By the best estimates, the most successful Basque fishing town only caught six whales per year in the 1500s and 1600s.[52]

The seemingly low volume of catches was due to the inherent difficulty of whaling and the enormous profits that a single whale could generate, especially given the low costs of the business. Even a single whale per year seemed to be enough to keep a significant portion of a fishing village in profit.[53] The industry was further supported by a fairly lax tax and regulatory attitude. For some reason, Basque whaling was entirely tax-exempt under French law, though the Basque sailors graciously gave all of their whale tongues to the church anyway. In the 1100s, the English monarchy inherited control of French Basque territory and began levying taxes on whaling. By 1257, whalers also had to pay a tithe (10% of value) on all hunted whales.[54]

The Basque attempted to expand whaling operations abroad with some success. They established coastal whaling operations in Ireland, Scotland, Norway, Iceland, Canada, and Brazil.[55] These operations seem to have inspired other nations to take up whaling and eventually surpass the Basque.

Dutch Days

Basque whaling hit its peak in the 1500s and 1600s and then went into steady decline. At the time, whaling was economically important for a few whaling towns on the Bay of Biscay and a handful of other villages on the European Atlantic coast and in Scandinavia, but it had yet to become more than a boutique fuel and food industry.

In the late 1500s, the Dutch burst onto the whaling scene and put the first real economic engine behind the industry. And by the early 1600s, the Dutch had easily eclipsed the Basque and become by far the dominant global whaling power. It’s easy to forget that for about a century, the Netherlands was the most dominant seafaring power in the world, and built a colonial empire which would persevere in some form until World War II. The backbone of this surging nation was its mercantile fleet which in the 17th century was probably larger than the fleets of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and the German states combined.[56][57]

The Dutch had lots of high-quality ships and a growing urban population, so moving into the whaling space was a no-brainer. They initially peeled off a few ships from their traditional fishing routes and first sent them down to the Bay of Biscay to hunt what was left of the sperm and right whale populations. But in the late 1500s, Danish merchantmen discovered massive whale populations around Spitsbergen, a group of desolate and otherwise economically useless islands in the North Sea which were then under the nominal control of Denmark (via its sovereignty over Norway). The land provided an empty and easily accessible spot to establish shore-based whaling outposts where crews could set up lookouts and have whaleboats on standby. The superabundance of whales kicked off a mini-whaling craze with the English granting monopoly whaling rights to its Muscovy Company and various other nations sending fledgling whaling fleets to get a piece of the action. But the vast quantity of well-built Dutch ships manned by skilled and experienced crews quickly swamped the others and captured a massively dominant market share.

Right whales were the initial target of the Dutch, but they soon found more traction with bowheads, which were similar enough to right whales in behavior and appearance that they were often confused for one another. Best of all, they produced equally high-quality oil, and the Dutch and other merchants found that harvesting whales in the frigid north was actually easier since the carcasses took longer to rot. The Dutch also innovated using the baleen harvested from rights and bowheads for expertly crafted cabinets.

From 1699-1708, the Dutch industry peaked with the dispatch of an astounding 1,652 whaling ventures which caught 8,537 whales. No other country came close to their fleet size, catch rate, or cost efficiency, with even the English only deploying a “handful” of vessels during the same time period.[58]

But then the Dutch whaling industry petered out and by the mid-1700s. I haven’t found a detailed explanation why this occurred. In Pursuit of Leviathan says, “political troubles between England and the Continental countries reduced Dutch access to British markets,” which were the major source of demand for whale oil.[59] Wikipedia says “political turmoil and warfare in Holland” undermined the Dutch fleet. So my best guess is that Dutch naval dominance was on the decline, and the British government pushed to limit their access to whaling sites to spur their own industry.

Part IV – The Anglo Whaling War (1700-1815)

If you just want to know more about whaling – life on the sea, hunting rates, the value of whale products, how the crews were paid, the risk-reward payout of whaling ventures, etc. – then you can skip this Part. If you want to know how a free market industry crushed a government subsidized/regulated/supported industry, then read on.

Albion On The Sea

The British were the dominant whalers from the mid-18th century until the early 19th century when the global whaling industry reached its peak under the United States. But unlike the artisanal Basques, the skilled Dutch, or eventually the ambitious Americans, the Brits didn’t rise to prominence because they were the best whalers… in fact, they seemed like chronically mediocre whalers. Rather, British dominance was achieved by heavy-handed government intervention both domestically and abroad, and pretty much the instant a foreign competitor wasn’t militarily besieged (the Americans), British market share tanked.

Local whaling operations had existed in the north of the British Isles throughout the late medieval and Renaissance eras, largely due to inspiration from the more intrepid Basque expeditions. British commercial whaling sparked to life in 1577 with the discovery of the Spitsbergen whaling grounds. In typical British fashion, the London-based Muscovy Company, which had been a generic shipping company, successfully lobbied the government to be granted a domestic monopoly on whaling.[60] The government even banned whale product imports from the Basques, primarily for political reasons, but also probably as a protectionist policy to support their domestic whaling industry.[61] But for some reason, the Muscovy Company only sent out a handful of whaling ships over the next three decades[62] and didn’t bother going to the hotspot Spitsbergen islands until 1611.[63]

More than half a century rolled by with the British whaling industry making little progress. The Dutch whaling operations were so efficient that they were selling whale oil to British markets at lower prices than domestic whalers could provide despite sizeable tariffs.[64]

In the 1670s, the British government decided to get serious about whaling. Through some not unreasonable logical leaps, they believed that a strong whaling industry could serve as a strategic asset both economically and militarily for the nation. Whale oil demand was steadily growing as Britain underwent urbanization, and the mercantilist government didn’t like the dragging trade deficit it held with the Dutch as they pumped barrels of oil into London in exchange for pounds. This was also the start of real British seafaring ambitions, and forward-thinking admirals wanted to imitate the Dutch model by cultivating fishing and whaling industries so Britain would always have a large stock of sailors to serve in the navy when needed.

Britain had good reason to want a whaling industry, but that didn’t change the facts on the water – they couldn’t compete with the Dutch. They had fewer ships, fewer sailors, less experience, and less expertise.

So the British government’s solution was to jump-start the industry with protectionism. In 1672, a law was passed exempting British whale oil from customs taxes and putting targeted tariffs on foreign whale oil and baleen. To their credit, the bill reduced restrictions to permit British whaling ships to carry a crew of up to 50% foreigners in the hope of dragging in skilled immigrants.[65]

The government support had little effect and the British whaling industry lagged, with single digits of British ships engaging in whaling annually. New hope came in the late 1690s when the Dutch lost some sort of diplomatic access to northern whaling territories and the British government granted a new whaling monopoly to the Greenland Company… which crashed and burned after multiple failed ventures, prompting the British government to forget about whaling for thirty years.[66]

But Britain was starting to come into its own. It was no longer a second-rate European power, but the head of maybe the second or third most powerful empire in the Western hemisphere. With a bit more confidence in the reach and efficacy of the state, the government tried again to spark the whaling industry, but this time with the brute force of pure subsidies: in 1732, a law was passed granting subsidies of £1 per ton of ship weight to whaling ship of over 200 tons.[67]

I’m afraid my seafaring knowledge is a little weak, but as far as I can tell, 200 tons wasn’t too large for a ship at the time. The fluyts which dominated Dutch trade were 200-300 tons.[68] Almost a century later, the average American whaler in 1838 was 283 tons.[69] Large British warships from the early 1500s were up to 1,500 tons.[70] 16th century galleons were 500-2,000 tons.[71]

By messy direct inflation conversion, £1 in 1732 = £252.52 in 2021[72] = $351.51. For reference, the average British farmer in 1730 made 10.8 pence/day[73] = £0.045 pounds/day = £13.5 pounds per year working 300 days. So by my rough estimates, even the smallest ships to pass the 200 ton threshold were getting subsidies that were enough to employ almost 15 full-time laborers per year, which seems like a pretty sizeable amount.

And yet… the British whaling industry didn’t improve. Annual output of whale oil didn’t budge.[74]

When a government policy fails, the natural course of action is to double down. So in 1740, the government increased the subsidies to £1.5 per ton.[75]

The result… four or five British whalers went out annually. And they mostly just bought whale oil from the Dutch and then resold it in London.[76] Even the early American industry based in Nantucket was sending out 25 ships in 1730 (albeit much smaller ones, 38-50 tons).[77]

In 1750, the British government again increased subsidies, this time to £2 per ton. Finally, the British whaling industry took off, with the number of whalers increasing from two in 1749 to 20 in 1750 and 83 in 1756. By the 1780s, they were fielding 200-400 vessels per year.[78]

Was this boom in the British whaling industry due to the government’s protectionist policies? Maybe. The government was paying whaleships a minimum of £400 just for setting sail, and that seemed to be enough free money to incentivize fisherman to try their hand at whaling. Alternatively, the sharp decline of Dutch shipping in the middle of the century finally opened up more and better whaling spots for British whalers which meant increased odds of profits, so maybe the British whaling industry was in the process of expanding anyway. Or, the soaring demand for whale oil – due not just to lighting in growing cities but lubrication for machines in the early industrial revolution – pushed prices high enough to justify more domestic whaling.

Regardless of whether government or market forces can take credit, the British finally became the dominant global whalers in the second half of the 18th century and would remain so until 1814. Britain had been the largest consumer of whale oil for a while, but now they were also the largest producers. With the evolution of ocean whaling (whaling in the open ocean as opposed to on the shoreline), British whalers went all the way to the Indian and Pacific Oceans by the 1780s.

Britain’s era of whaling glory overlapped heavily with its era of naval ascendency, which meant constantly fighting European and colonial wars. Usually, these wars hindered the whaling industry both because foreign naval ships and privateers would hunt whalers, and because the British navy would pressgang its own whalers.

But wars also proved to be the saving grace of the British whaling industry. Not only did the legendary British navy secure the largest and safest sea access the world had ever known, but two particular wars destroyed Britain’s greatest whaling competitor.

By the 1770s, the American colonists were sending out 300 whaling ships per year.[79] And though these ships were significantly smaller than British whalers, they had access to the rich whaling waters of the Eastern American coast while the British either had to go to the frigid North Sea or distant oceans. But just when the spunky Americans looked to be seriously undercutting British whaling (despite the massive disadvantage that they could only sell to American and British markets due to British protectionist laws), the War for American Independence broke out and the mighty British navy destroyed the vast majority of American ships of all varieties. The American whaling industry basically disappeared for a few decades, and just when it was resurging once more, the War of 1812 smacked it back down.

Eventually, the Brits couldn’t stop the inevitable. American whaling exploded right after the war ended and soon became the most dominant in the world. The British government was tired of paying high subsidies, and the British whaling industry still wasn’t particularly efficient, so they began to allow American whale oil imports to take prominence over domestic production. The final nail in the British whaling industry’s coffin (or at least the definitive end of any pretense of British dominance) was the wave of free trade sentiment which began sweeping Britain in the 1820s. In 1824, whaling subsidies ended, in 1843 tariffs on whale products were greatly reduced, and in 1849 whaling tariffs were eliminated entirely. By then, Britain barely had a whaling industry.

How the Whales Were Won[80]

Whaling is in America’s blood. The pilgrims on the Mayflower saw whales on their voyage to Massachusetts and many passengers wrote about it in their diaries. Pretty much every 17th century coastal New England town was set up at a whaling operation and hoped to one day harvest the beasts. The Native Americans living along the northeast coast hunted whales, and taught the Europeans how to do so in many places. Coastal whales were so abundant that an early Cape Cod resident claimed to have seen enough in the bay at one time to stretch across its entire length. Hyperbole maybe, but you get the point.

Colonial Americans harvested beached whales when they could (though they usually had to give the church a taste) and occasionally joined Native Americans in their hunts, but it wasn’t until the early 1700s that a proper commercial whaling industry developed in Nantucket, an island off the coast of Massachusetts. As a port town with a well-established fishing industry and lots of experienced whaling Natives, it was an ideal site, though its best attribute was simply being surrounded by lots and lots of whales. The early coastal whaling outposts found them so easy to spot, and the right whales so easy to kill, that the island more-or-less abandoned its cod fisheries for whaling.

The techniques that would come to be standardized in the Golden Age of whaling a century later were developed here. The Nantucket sleigh ride was a terrifying and exhilarating right-of-passage for whalers who zipped around the ocean following their prey. Harpoon designs, crewmember positions, and harvesting methods were developed over the decades as the industry grew.

One of the key developments was the lay system. Unlike British whalers who were largely paid on a salary basis, Americans were paid with profit-sharing. Each crewmember negotiated his own lay, or fraction of the profits, based on his post, experience, and negotiating prowess. I’ll give a full breakdown of how this system worked in Part V, but generally the whaling companies kept about a third of profits for themselves, officers received between 1/15th and 1/30th each, and other crewmembers around 1/100th to 1/300th each.

The whaling company owners and officers in Nantucket were nearly always white Quakers. The idea of one of the most pacifistic religions on earth leading the slaughter of giant, majestic animals is a bit odd, and Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America even says that some of them struggled with the morality of the profession. But apparently the money was worth a bit of bloodshed.

The rank-and-file whalers were mostly native Americans and blacks, though there were occasional poor whites. There was no direct legal reason for this divide, it was just a matter of capital and expertise. The white officers tended to be highly experienced fisherman, merchantman, or naval officers; the Native Americans were experienced whalers, but willing to accept low wages; and the blacks were usually inexperienced migrants who also accepted low wages, though there was at least one whaling company owned and operated by a black man.

(On a less progressive note, American whalers sometimes took jobs as slave transports since the ample cargo holds of whaleships made them well-suited to the task).

The oddball demographic addition to the whaling industry was the Portuguese, who typically have no presence in American history, but had a major role in American whaling. For some reason, the meager number of Portuguese colonial Americans settled in and around Nantucket, and since they tended to have sailing expertise, a ton of them joined the whaling industry. Though they were usually crewmen instead of officers, they were considered the most-skilled, most valuable, and highest paid of the bunch.

American colonial whale hunters were relatively few in number and used much smaller ships than their European counterparts, but they were good… really good. They hunted at a higher rate of efficiency than their British and Dutch counterparts, and the American companies expanded rapidly with their profits. Over the first half of the 18th century, their whaling output climbed precipitously, and by the mid-century, they may have eclipsed the British in oil output, though my two main sources seem to disagree on this point.

By 1750, there were 100 American whaleships. Twenty years later, there were 370 American whaleships which annually produced 45,000 barrels of sperm oil and spermaceti, 8,500 barrels of other whale oil, and 75,000 pounds of baleen. American whaling probably could have entered a Golden Age as early as the 1760s (as opposed to the 1810s) were it not for political conflicts and government meddling messing up the industry for 50 years.

In the 1750s, American colonists and Native allies fought against French colonists and their Native allies in the French and Indian War (AKA Seven Years War) over the fate of North American colonial territory. Whaling operations slowed to avoid French privateers and would have recovered after the war, except the British government infamously began squeezing the American colonies with taxes and protectionist trade measures ostensibly to pay for the war effort.

By that point, American whale oil was so plentiful and cheap that it easily undercut the heavily subsidized British production. Due to sheer domestic demand, the British government was forced to lower its oil tariffs against its colonies, but it maintained high tariffs with all other nations, which in turn raised their tariffs defensively against Britain and its colonies. This forced the Americans to sell the vast majority of their oil to mainland Britain since they were priced out other markets (like France and the German states). American whaling was further hindered by the Restraining Acts and Intolerable Acts which limited whaling grounds and closed New England harbors.

With the outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1775, the whaling industry came to a virtual standstill. The British owned the waves and were happy to pick off any American merchant vessels as accomplices to the rebellion. This is also when the British began their (IMO severely under-historically-resented) practice of impressing American sailors into service in the British navy. If losing one’s cargo and ship weren’t enough to dissuade American whalers from plying their trade, the risk of indefinite enslavement and being forced to fight against their countrymen was.

(In a cruel display of history rewarding evil, Leviathan: The History of Whaling in America says that a significant portion of the successful post-Revolutionary War British whaling industry was driven by impressed American whalers brought back to Britain after the war. Many of them became specialists in British crews and/or taught their whaling expertise to the Brits.)

At the time, almost all American whaling was concentrated in New England, and almost all New England whaling was concentrated in Nantucket, which itself was almost entirely dependent on the whaling industry. Therefore, the war was a disaster for Nantucket – they couldn’t hunt with the British patrolling the seas, and even if they could, they wouldn’t be able to sell their oil to the British who had been their almost exclusive customer for a decade. Loyalist sentiment was high on the island (probably due to economic self-interest) and so the people of Nantucket felt like they were really being screwed by the war. If they had it their way, they would continue to hunt and sell to the Brits like nothing had changed.

This prompted an odd historical footnote – the Nantucket government basically tried to operate as an independent nation during the American War for Independence.

At first, the island seriously considered declaring independence from the United States of America, but given that New England was a stronghold of patriot support, they were understandably concerned about being invaded and forced back into line.

So Nantucket decided on a weird compromise route of sending a delegation to the Massachusetts government to ask if it could operate as a de facto independent state and negotiate with the British government on its own terms while remaining legally within the bounds of the new United States. To which the Massachusetts government responded with a resounding: “No.”

But the Nantucket government wasn’t ready to watch its economy collapse, so it ignored the Massachusetts government and tried to independently negotiate with the British anyway. They sent delegates to the crown and attempted to buy licenses to engage in whaling without being harassed by the British blockade, which the Brits agreed to, because I guess it was free money and sowed division in the colonies.

Unfortunately, the licenses didn’t really work. Nantucket did a little bit of whaling, but a lot of their ships were captured and whalers impressed into service anyway. It’s not clear why this happened, but presumably the British naval high command didn’t care enough about the licensing deal to seriously enforce it. The Nantucket government tried resetting the terms of the deals numerous times, but always to the same result. Worse yet, their attempts to stay loyal to the crown couldn’t prevent a British naval squadron from launching a full-scale raiding expedition of the island and destroying much of its fleet.

In 1783, the Revolutionary War came to an end and the United States of America emerged as a free and independent nation. It was a new day and age for whalers. The seas were open, the British trade regulations were gone, free-ish trade was the new default policy, the Massachusetts state government started a small whale oil subsidy, and so there seemed to be nothing stopping the American whaling industry from resuming its meteoric rise to global dominance…

Except the British again. With a booming industrial economy, Britain was still by far the largest source of whale oil demand, and with near-monopsony power, British trade policy could steer the whole market. Both out of a desire to finally make British whaling work, and due to a petty drive for revenge against America for winning the war,[81] the British government slapped an enormous tariff on American whale oil, which by one contemporary estimate was twice the expected profit per barrel.

This one law pretty much re-crippled the American whaling industry. Yet again, Nantucket seriously considered seceding from the United States, and when this plan was abandoned, its most prominent whalers attempted to move to Halifax, Canada to relaunch the industry within the British Empire. But the crown ordered the governor of Canada to block the move literally out of spite. For the next few decades, the remaining 100 or so American whalers did their best to keep the industry going, but faced low non-British demand, and periodic harassment from British and French privateers who willfully disregarded American neutrality while they fought each other in the Napoleonic Wars.

The saving grace for American whaling was that its whalers were really, really good at whaling. There were so good that eventually the British and French governments tried making deals with the Nantucket whaling community to ship their entire operation to Europe. Land, houses, subsidies, lump sum up-front bonuses, and preferential trade rights were offered, and eventually the American whalers took a deal with the French to relocate near Dunkirk. In the end, only a handful of families agreed to the move and the bulk of American whalers stayed behind, but the small contingent formed a boutique, yet highly profitable French whaling industry to compete with the British.

The final pummeling of American whaling was the War of 1812. Once again, the mighty British navy easily blockaded all of the US. Once again, lots of whaling ships were captured and whalers impressed into British service. Once again, Nantucket tried to operate as a quasi-independent nation, and even had the gall to stop paying American taxes for a while. In 1814, the island’s government even signed an official peace treaty with Britain two years before the war ended.[82]

Why Did the Americans Beat the Brits?

Why were the British so bad at whaling that they could only build their industry through tariffs, heavy subsidies, boxing out one competitor, and literally destroying another competitor? In Pursuit of Leviathan tackles this question:[83]

First, the Brits had a problem with a lack of homegrown whaling talent. Most of the whaling expedition leaders in the mid-late 1700s were actually American immigrants who moved to Britain for the subsidies or were press-ganged by the navy and stuck around for the business opportunities. Meanwhile, the best crewmen on British ships were nearly always Dutch, Portuguese, or Scandinavian, to the point where the British government had to relax labor laws in the middle of the century to allow a greater proportion of foreign workers on each ship.

This seems strange given the historical reputation of British seafaring… maybe the best sailors were absorbed into the navy, leaving only the second rates for commercial activity? One possibility suggested by In Pursuit of Leviathan is that British sailors were paid in a mixture of wages and commissions, while Americans were paid almost entirely in commissions. For high-risk/high-reward work like whaling, commissions offered better leverage and were more attractive to workers. So why didn’t the British pay higher commissions? I don’t know.

Second, British whaling was subject to numerous government regulations and supports which both raised industry costs and fostered inefficiency.

One protectionist law forced British companies to only purchase ships from domestic manufacturers, and while British ships were of high-quality, they were also expensive by international standards due to high resource and labor costs. Incidentally, the United States had this same law, but far lower shipbuilding costs. By best estimates, it cost 1.5-2.2X to build an equally sized ship in Britain than the US, though the British costs were partially offset by lower interest rates.[84]

While British whaling may have only gotten off the ground due to generous government subsidies, this support also pushed British whaling in a less cost-effective direction. The subsidy was paid out on the basis of ship size, which encouraged British whalers to use larger ships. In 1815, the average British whaler was 323 tons while the average American whaler was only 169 tons (though it would later rise considerably).[85] This shifted the British industry to embrace a higher labor-to-capital ratio since larger crews were needed to man the larger ships, and crew costs scaled faster than ship costs. The average American whaling crew during its golden age was 29,[86] compared to 40-50 for Britain.[87]

An unintended consequence of this shift was that British whalers were incentivized to make shorter ventures since venture length had a much greater impact on labor cost than capital cost. British ventures were typically seasonal and might max out at one year, while by the mid-1840s, most American ventures lasted more than two years. Thus, British whalers spent a relatively large amount of time going to-and-from whaling points compared to the Americans, and they spent less time at the whaling points overall, which contributed to a generally lower catch rate and cost-effectiveness.

Another more general side effect of the regulations and subsidies was that British whaling stagnated in technique while Americans were more experimental. US whalers used a larger variety of ship types and sizes, more diverse crewmembers, and went to far more whaling spots. The British mostly stuck to big ships, mostly British crews, and a few well-worn whaling spots.[88]

Finally, British whaling lost a disproportionately high number of ships to northern ice flows. They didn’t hit icebergs (often), but rather got stuck in quickly freezing waters in the late autumn, and then the crews would often freeze or starve to death. This was not as much of a problem for American ships when they eventually got into arctic whaling because they would plan to get stuck during their long ventures, and bring enough supplies to last through the long, cold, boring, desolate winters.

Part V – The Golden Age of Whaling (1815-1861)

Throughout the entire span of human civilization from about 10,000 BC to the present day, there was a period of about fifty years when one of the most important industries on earth was whaling. The Western nations had pulled ahead of the rest of the globe, their populations were growing, their cities were expanding, and their people needed light for their homes and streets. Centuries of commercially-based economic growth were slowly being supercharged by industrialism, and the factories springing up around the Atlantic needed lubricant for their gears and wheels.

In the past, people didn’t need as much light and lubricant, and in the future they would have endlessly abundant petroleum and new resources. But for a brief historical moment, the easiest, cheapest, fastest way to keep civilization growing was to sail to the far corners of the earth, hunt the largest animals to ever live, and drain their bodies for organic fuel. When people picture whaling in their minds, they think of this Golden Age: large ships leaving port, muscle-bound men carrying harpoons, thrashing whales knocking over boats, Winslow Homer, and Moby Dick.

The era was launched when American whaling was finally unleashed. At the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain ended its naval blockades and impressment policy, the French navy was dead, and so the sea was finally clear of privateers. Meanwhile, a wave of free trade enthusiasm swept over a British people sick of paying high prices for goods the Brits simply weren’t good at producing. Whale oil tariffs plummeted and were virtually eliminated by the 1840s, finally giving the US unhindered access to the largest source of oil demand in the world. The British whaling industry promptly collapsed along with its subsidies as consumers chose far cheaper foreign oil. Finally, after a long journey to figure out where to settle, the Nantucket whaling industry moved nearly its entire complex to the minor port town of New Bedford, Massachusetts, partially to tap into a growing pool of sailor labor, and partially because Nantucket’s shallow waters were proving troublesome for the newest generation of large ships.

In the forty years following the War of 1812, the global whaling industry would expand by something like 8-10X. From 1816-1820, the American whaling industry consisted of about 50 ships totaling over 18,000 tons, which earned an annual revenue of $750,000 (in 1880 USD).[89][90] At the peak of its size from 1841-1845, the industry had 672 ships totaling almost 186,000 tons.[91] A decade later at the peak of its revenue, the industry earned almost $10 million annually,[92] making whaling the fifth largest industry in America.[93] Prior to the 19th century, the global whaling industry hunted maybe 2,000-3,000 whales per year; at its peak in the 1800s, the global whaling industry probably peaked at 10,000-12,000 whales per year.[94] American whaling constituted about 70% of the global whaling industry, and New Bedford constituted about 45% of the American whaling industry, which made it the wealthiest city in the United States on a per capita basis.[95]

(It’s tough to put these numbers in perspective, but as points of comparison: in 1850 the federal government spent $45 million.[96])

We have far more historical data on this whaling era than any other. American whaling companies were good at recordkeeping and the port towns where they made home have done a great job of preserving their ledgers for posterity. American sailors were comparatively literate and used their excruciatingly long voyages to keep journals on daily life. So in Part V, I’ll dive into more of the minutiae of whaling, from the corporate operations to the labor agreements, and from life on the sea to the impact of the Golden Age on the global whale population.

The Market

Prior to the Golden Age, whaling had been an organized industry in Europe for at least 300 years. Why did it suddenly multiply 8-10X in supply and demand within a few decades?

My understanding is that there was a confluence of three factors. First, there was a soaring demand for whale products due to rising populations, urbanization, and industrialism. Second, whale products definitively outcompeted their competitors in quality. Third, due to the removal of political barriers, the supply of whale products was finally allowed to expand, thereby reducing prices and pushing the industry to market dominance.

The most important product was still whale oil, which was used primarily for lighting, and secondarily for industrial lubrication. It could be fed into lanterns to produce a relatively bright, yellow glow. It also had a fairly low freezing point which made it suitable for northern climates, and it was famously stable, with little-to-no risk of explosion or creating fires. The main drawback as a light source was its smell, which was said to be “fishy.”[97] Whale oil varied in quality which determined the brightness, hue, freezing point, and smell of the lanterns, but the best whale oil was the spermaceti oil (which was usually used as a candle rather than in lanterns) which burned bright white, had an extremely low freezing point, and gave off no odor.

It was the perfect product for the perfect time. People wanted to stay up at night, and whale oil was providing a higher quality way to light their homes than ever before. Soon the largest customers of whale oil were not retail consumers, but wholesale municipal governments as cities purchased huge quantities of whale oil for streetlights on their ever-expanding (and often crime-ridden) avenues. Finally, lighthouses became a major purchaser of whale oil, particularly spermaceti oil for its brightness. This was the heyday lighthouses, and thousands lined the American shores, all of which had an extremely powerful beacon that needed to shine 24/7.

Whale oil had plenty of lighting competitors both historically and that emerged to challenge its dominance during the Golden Age. I found this part of my research surprisingly interesting… the marketplace was keenly aware that growing cities had yet to find a viable lighting source. There were lots of companies, inventors, and merchants fiddling around with known and obscure fuel sources trying to find the next big lighting breakthrough, with widely varying levels of success. Lots of competitors emerged, but ultimately whale oil outcompeted them all, at least for a while. Alternatives included:

Lard oil, a derivative of pig fat, entered the marketplace in the 1830s. It was cheap (usually about 25% less expensive than whale oil), abundant, and easily made. But it smelled horrible, burned unevenly, its candles had a tendency to collapse, and the light was too faint for most contexts. Despite innovations, lard oil was mostly used in rural areas where port-drawn whale oil was more expensive.[98]

Vegetable oils derived from various plants (mostly canola and soy) were being innovated throughout the first half of the 1800s. Most had the same advantages and disadvantages of lard oil, making them cheap but inferior alternatives to whale oil. But they did slowly improve over time and eat away at whale oil market share.[99]

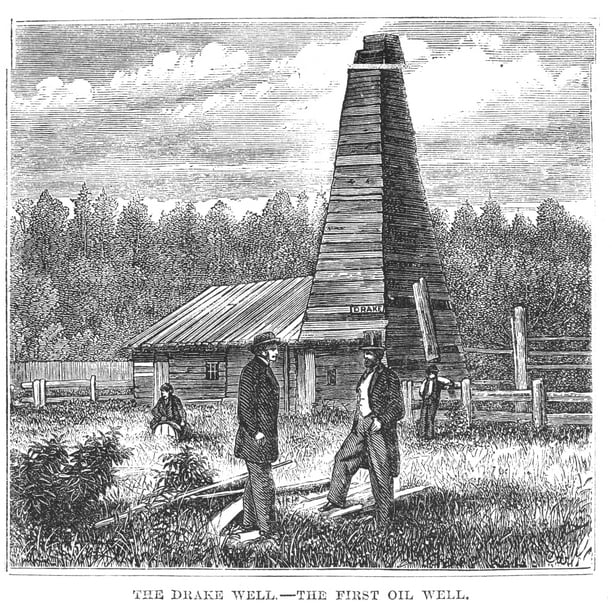

Camphine was a novel compound of lard oil, vegetable oil, alcohol, and turpentine (a flammable liquid distilled from tree resin). When it first came on the market in the 1840s, it looked like the whale oil-killer had finally arrived. It was far cheaper (about 1/3rd-1/5th the price), burned brightly, and was easily fed into lanterns. Its only problem was its tendency to explode. Various sources I read referred to it as “volatile” and “dangerous,” which makes camphine lanterns not well suited for sitting above beds in wooden houses in the 19th century.[100][101] Most notably, in 1846 a camphine lantern burned down the St. Louis Theater, killing 45 people. Camphine stuck around throughout the mid-century, and some people say it had a brief moment of market dominance before alcohol taxes jacked its price up, but the substance was never able light much of America for long.[102]